In 2021, Funimation viewers got what might have been their first introduction to donghua when the anime streaming service added the series Heaven Official’s Blessing to its roster. But the service mistakenly listed the language on the Chinese import as “Japanese.” (It’s since been corrected to “Mandarin.”) Netflix is also streaming the series — under the banner of its “anime” category. Cue confusion from curious viewers who saw previews and asked, “What anime is this from?” The most straightforward answer: “It’s anime-style, but it’s Chinese, so we call it a donghua.”

“Donghua” — much like “anime” for Japanese speakers — is simply the Chinese word for “animation.” After decades of stagnation in the animation industry, going as far back as the Cultural Revolution, China has entered what many tentatively call a rebirth in the field. It’s the result of 20 years of a Chinese identity crisis in animation, as the industry struggled to compete with the likes of Disney, Pixar, and Japan’s famed Studio Ghibli.

While donghua’s current form is heavily influenced by anime, it has its own identity. From the beginning, the medium has constantly evolved to meet the mindset of the society it comes from.

Chinese animation has been around for nearly a hundred years. The first few donghua pieces, originating in the 1920s, have been lost. But the golden and silver ages of Chinese cinema introduced signature animation styles based on traditional arts: shadow puppetry, paper-folded stop-motion, ink wash painting, and the brightly colored pomp and panache of Chinese opera.

Milestone 1: Nezha Conquers the Dragon King

Enter the Cultural Revolution. The messaging and style of donghua changed to essentially become inspirational propaganda posters in motion. Meanwhile, Chinese society experienced a decade of upheaval that didn’t end until 1976.

Image: Shanghai Animation Film Studio

The aftermath of such emotional and ideological times is apparent in 1979’s Nezha Conquers the Dragon King, a donghua that continues to introduce many Chinese nationals and expats to a folkloric hero. Nezha, third noble heir of the coastal town Chentang Guan, is just a child when he kills Ao Bing, the son of the Eastern Dragon King, for eating children as offerings for rain. When the Eastern Dragon King summons his brothers to flood Chentang Guan in retaliation, Nezha’s father punishes him. Nezha, in a filial act, kills himself to appease the dragons, save the people of Chentang Guan, and return his body to his parents.

This adaptation of a folkloric story was released off the heels of the Cultural Revolution, and reflects its theme of violent uprising against abusive authority figures. It has been interpreted both as an allegory for the Cultural Revolution itself or for its ending, when its political perpetrators were overthrown. No matter which interpretation you accept, though, the core message continued to evolve through decades of further adaptations of Nezha’s story.

The animation and design of Nezha Conquers the Dragon King were considered a return to traditional characteristics: During dramatic scenes, the music is played by a familiar Peking opera ensemble, which was viewed as an obsolete, out-of-touch art during the Cultural Revolution. The exaggerated movements, facial features, and body proportions — especially the wide shoulders of heavyset men — reflect a combination of opera and ink paintings. It is a piece of nostalgia informed by a period of turmoil.

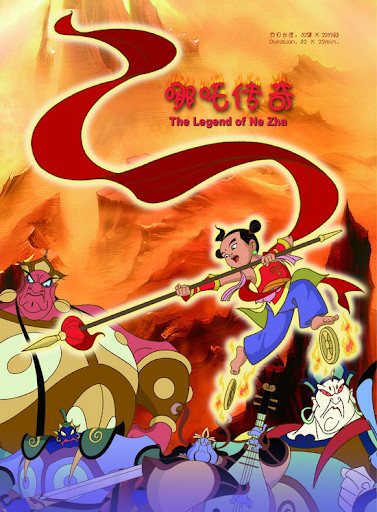

Milestone 2: Legend of Nezha

By the 1990s and early 2000s, donghua had entered a period of stagnation. Animated movies like Disney’s 1989 feature The Little Mermaid ushered in the Disney renaissance. Meanwhile, anime like Dragon Ball and Sailor Moon became so popular, they built huge and lasting international fandoms.

During this time period, China had begun introducing economic reforms to ensure a steady upward growth. But Japan and the United States dominated the global animation market. Caught between these two giants, China could not compete.

Nezha rushed back on screen, this time in 2003’s Legend of Nezha, a donghua series whose ending theme children still sing today. This time, the story covered the text of the entire original story, historical context and all. But it still emphasized the theme of overthrowing a despot.

Image: China International Television Corporation

The visuals were designed with a combination of Disney and anime looks, featuring big-eyed characters and widely drawn lines. Legend of Nezha and other donghua of this period were only domestic releases. If they made it to global distribution, it was only through Chinese diaspora enclaves.

During that period, donghua was largely seen as clunky, cheap animation, operating under the familiar stigma of anything labeled “made in China.” Both industry expansionists and Chinese people at large are still trying to shake off that association. It certainly didn’t help that China was seen as a source of cheap animation labor, with donghua artists prioritizing outsourced work for Japanese studios over working with local studios. Many of the backdrops seen in anime of the era were drawn in China.

As accessibility to the internet expanded in the mid-2000s, the game changed. Amateurs began using online sites to distribute their own homemade animation. And the outsourcing of anime work to China had trained an entire generation of artists in what had become a popular style worldwide.

China rolled out regulations that restricted airtime for foreign works, leaving plenty of room for domestic donghua. The country’s economy, which had been steadily but surely growing, reached such a bullish height that the government began funding the donghua industry. Private investors began pouring money into the art.

Milestone 3: Monkey King: Hero Is Back

2015’s Monkey King: Hero Is Back was a turning point. This feature film, starring another oft-adapted folklore character, was crowdfunded — a model of investment so popular at the time, companies like Alibaba jumped in on it too.

The story this time around was not a verbatim adaptation of a familiar folk tale, but a broad reimagining of one. The visuals and effects were updated with computer animation, and it was the style that struck a chord with the audience. As Accented Cinema, the Chinese Canadian YouTuber and film essayist, puts it: “The familiar Chinese music, the ribbons and the exaggerated proportions of gods, the stylized clouds and mountains… It’s all so familiar. But now the action is like anime. After 20 years of soul-searching, my generation finally grew up.”

Monkey King: Hero Is Back made its production budget back twice over. It was the highest-grossing animated movie in China until Zootopia and Kung Fu Panda 3 broke the record.

Milestone 4: Big Fish & Begonia

The upward trajectory continued, and this time pierced the international market. Funimation dubbed 2016’s Big Fish & Begonia, another feature-length donghua. Big Fish & Begonia is a myth-like fantasy story that focuses on an underwater being, Chun, who surfaces into the human world in the form of a dolphin. When a human drowns while saving her from a net, Chun makes a deal with an afterlife caretaker to tend to the soul of the human, which itself takes the form of a baby dolphin.

Image: Horgos Coloroom Pictures, Beijing Enlight Media, Biantian (Beijing) Media, Studio Mir

Audiences were drawn to its existentialist themes. The film explores the balance of nature and society, personal bonds that overlap the two (Chun seeks advice from her grandfather, who is a tree), and the nature of reincarnation, which Chinese audiences would recognize as a trope in its fantasy genres.

What reviewers and social media fans praised in particular was the aesthetic delivery of these themes. “It is unsurprising, but also unfair, that the film has repeatedly drawn comparisons to Studio Ghibli,” wrote one Reddit reviewer. The smooth animation and the character designs draw from the Classic of Mountains and Seas — a Chinese text not unlike Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. The previews and music videos heavily featured the tulou, a region-specific Chinese home used incorrectly in 2020’s Disney movie Mulan. But what grabbed people’s attention the most on social media was the main theme, “Big Fish,” which became singer Zhou Shen’s claim to fame. It even caught attention in the West, with song covers all over YouTube. Zhou Shen has continued to garner English-language comments on the site. This may be the first donghua in recent years to gain popularity in the Anglosphere.

Milestone 5: Nezha

Nezha came back in 2019, this time on Netflix. Like Monkey King: Hero Is Back, the new feature-length donghua reimagines the character’s story for a new generation. Nezha is now a social outcast whose only friend is the character he murders in the original text, Ao Bing. In this version, they’re both children of circumstance, whose families dictate they be enemies.

That inherently makes the story about fighting destiny. Instead of pursuing a rocky path to filial piety, this Nezha questions filial loyalty altogether. It hit home for a generation of millennials in China — a generation whose young people are traveling internationally more than any time in history, and whose parents fret because they’re marrying years after the “acceptable” age to be single (if they marry at all). This is where women are choosing to become single mothers, shattering expectations of what a family should be. Globalization and economic growth have created a literal world of opportunity to pursue, but parents unused to the change still expect young people to start families instead. Social norms are in a major state of change, and this latest breakout donghua hit reflects that tumult.

Image: Chengdu Coco Cartoon/Beijing Enlight Pictures

Nezha keeps the elements that make donghua culturally unique. It uses a randomly placed Peking opera ensemble to create a comedic reference to the original Nezha Conquers the Dragon King. The biggest shift from traditional donghua may be Nezha himself. His character design departs from the round, almost cherub-like face that shows he’s a child. In this adaptation, his exaggerated facial features reflect styles drawn from the wild-eyed grimaces and generous mouth signature from a wide range of characters found in Chinese paintings and sculptures — from demons to deities like the Four Heavenly Kings to more historical figures like Bodhidharma. The trope of an ugly, socially vilified protagonist may even resemble digital “monster” characters in the West, like Shrek. Regardless, it is a departure from an attempt to imitate both American and Japanese influence. To quote Accented Cinema’s delight in his new design: “I mean, if they wanted to copy Disney, they wouldn’t make Nezha an imp. Oh my God, he’s so ugly, I love it.”

The film’s iconography includes supernatural door guards in ancient bronze masks found in archeological digs throughout China. Nezha’s master swaggers around in exaggerated proportions and speaks Sichuan dialect — a localized choice for a film in standard Mandarin. It isn’t just about making a new identity — it’s about reconciling the new world with the one they came from.

Because of its cultural specificity, the new Nezha and its characters resonate in diaspora communities outside of China itself. At Anime NYC in 2021, popular artists like the Chinese American Velinxi sold prints featuring Nezha’s new iteration with his former murder victim turned best friend, Ao Bing.

Although much of her work is based off familiar Japanese and Western stories with preestablished fan bases in the United States, she has begun drawing for a new wave of media based off Chinese storytelling, including Strike the Zither, a retelling of the novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Chinese American author Joan He. Joan He, herself raised on media from China, has said, “Journey to the West was basically my SpongeBob.”

Milestone 6: MXTX

While donghua is reimagining old pantheons, it’s making new ones as well. In college, Chinese indie author Mo Xiang Tong Xiu penned three books. The most famous, Mo Dao Zu Shi, was adapted into a donghua series in 2018. Then it was adapted into 2019’s The Untamed, a live-action drama available on Netflix and YouTube. They are many people’s introduction to each respective medium. Chinese diaspora often identify Mo Dao Zu Shi as the first story they could share outside the community. Heaven Official’s Blessing, her third novel, has since followed suit on Funimation.

Donghua among anime and manga fans

Image: Tencent Penguin Pictures, B.C May Pictures

For casual viewers — especially fans who watch imported animation in English — it’s standard to lump donghua movies and features in with anime, especially if they are anime-style. Mo Xiang Tong Xiu’s books, officially released in English in December 2021, are marketed as light novels under the “manga” section of Barnes & Noble; Seven Seas, the publisher that holds the license to these books, traditionally translates Japanese books. Western marketing — especially American marketing — has offered Japanese stories as the default East Asian media for so long now that they typically pitch other countries’ works under the same grouping.

Korean manhwa (comics) are often given the same treatment, filed in the manga section of bookstores, isolated from the comics section that carries graphic novels from the Western world.

American impact is just as strong: The double standard

Like each Nezha adaptation, MXTX uses an ancient historical backdrop to tell themes that are ruminating in Chinese people’s minds now. Even the name Heaven Official’s Blessing — “tiān guān cì fú” — is a Daoist phrase still found on commercialized talismans in China.

Donghua exists in its current form due to a close relationship with anime, but such broad categorizations and blatant mistakes raise the question of if people even recognize East Asian works and the people behind them as separate cultures.

It also ignores the equally heavy impact of American animation.

China became the world’s second-largest entertainment market in 2017; the first is the United States. The two actively work together: Kung Fu Panda 3 (2016) and Netflix’s Over the Moon (2020) are both co-productions between American and Chinese production companies, and both stories are set in China. The primary producing company for both films, Pearl Studio, is based in Shanghai but made up of both locals and former Disney and DreamWorks creators from the United States.

Generations of influence by Japan and the United States’ soft power is inevitable for any country; they are two of the biggest animation markets in the world. Before the pandemic, the biggest Japanese pop culture convention outside of its country of origin was Japan Expo, based in France. When Disney’s Coco was released in 2017, a Peruvian father-son duo dubbed the film in Quechua, the most common Indigenous language still spoken in South America. China is no exception. Donghua is unique because it is the reckoning of identity by a third country that has put the resources into matching the giants toe-to-toe.

By extension, it is a reckoning not only for that country’s domestic people, but its global diaspora as well. Just as Europeans flock to celebrate the anime, manga, and video games they love, Chinese people and the Chinese diaspora have drawn from fluid Japanese animation. Just as this Peruvian father and son wanted to share Coco with their village and the 8 million speakers of their language, Chinese and diaspora people have sought to express their love for American storytelling with their own culture.

Through decades of innovation and cross-generational conversation, donghua has become something to be proud of. Chinese people, the largest ethnic group in the world with just as many complexities, have a form of animated storytelling all their own. It deserves more than to be haphazardly lumped into the category of “anime” simply because it too comes from East Asia. The conflation of all things East Asian as a part of one category is a dangerous one, be it with art or with people.