On Tuesday, the U.S. Senate passed a bill that would force TikTok’s China-based parent company to sell the popular app, or it would be blocked in the U.S.

While the legislation would have profound impacts across the tech, political, entertainment, media and marketing worlds, music may be especially affected. TikTok’s first incarnation was as a lip-syncing app, Musical.ly, and the app dominates music discovery for young listeners. If the app were banned in the U.S., it would upend the ways artists communicate with their fans, how old songs gain new life (and huge publishing deals), and how 170 million American users discover new music.

Earlier this month, The Times published a long look at the future of TikTok in the music industry. Here are some of the ways Tuesday’s news might affect it.

Who voted for this bill, and how would it impact TikTok?

The Senate bill gives TikTok’s Chinese parent firm ByteDance nine months to sell TikTok, with a possible three-month extension if a sale is imminent. The bill also stops the company from controlling TikTok’s algorithm, its uncannily compelling recommendation engine for new videos. The bill, passed 79-18, was part of a $95-billion package that also provides aid to Ukraine and Israel. The House of Representatives already passed similar legislation last week, citing concerns about data security and foreign influence. President Biden said he will sign it Wednesday.

“Congress is not acting to punish ByteDance, TikTok or any other individual company,” said Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.), chair of the Senate Commerce Committee, in remarks in the Senate this week. “Congress is acting to prevent foreign adversaries from conducting espionage, surveillance, maligned operations, harming vulnerable Americans, our servicemen and women, and our U.S. government personnel.”

How has TikTok responded?

ByteDance has said it is not inclined to sell TikTok to comply with this legislation, and would instead seek to block the law in court.

The Associated Press obtained a memo from Michael Beckerman, TikTok’s head of public policy for the Americas, who said that “At the stage that the bill is signed, we will move to the courts for a legal challenge. This is the beginning, not the end of this long process.”

That strategy has been successful in some cases — in November, a federal judge blocked a Montana law that would have banned TikTok in the state.

Isimeme Udu, the singer who performs as Hemlocke Springs.

(Ana Peralta Chong)

What does it mean for the music industry?

Many artists are already under a de-facto TikTok ban. Universal Music Group, the largest record label conglomerate in the country, has already pulled its catalog from the service.

In a January open letter, UMG said that “TikTok proposed paying our artists and songwriters at a rate that is a fraction of the rate that similarly situated major social platforms pay … Ultimately TikTok is trying to build a music-based business, without paying fair value for the music. TikTok’s tactics are obvious: use its platform power to hurt vulnerable artists and try to intimidate us into conceding to a bad deal that undervalues music and shortchanges artists and songwriters as well as their fans.”

A source familiar with UMG’s strategy for TikTok said that its catalog pull hasn’t notably affected streaming figures on other platforms, citing a recent Luminate study which found only a 1.8% drop in UMG’s market share of on-demand streaming audio (from 38.72% to 38.02%, which they said was within the normal range of the release calendar) in the eight weeks after UMG withdrew. UMG’s deal with TikTok was responsible for about 1% of its annual revenue.

Some label executives are happy to see the app humbled. Sarah Flanagan, a former senior director of digital marketing at Columbia Records (which is not part of UMG), said that “TikTok hasn’t figured out a way to compensate artists or labels fairly for the amount of music that gets used. As great as it’s been for music discovery, I hope this works, because TikTok’s system for compensating artists is either not good enough or they don’t care enough.”

Yet labels’ and publishers’ main complaint is that the service isn’t paying enough for rights to their catalogs. They’d likely rather have a world where TikTok exists for marketing, but pays more like Spotify or YouTube. Virality can reap big rewards — in 2020, months after Fleetwood Mac’s classic single “Dreams” took off on TikTok, Stevie Nicks sold a majority of her publishing catalog for $100 million.

Members of the rock group Fleetwood Mac celebrate their Grammy Award in Los Angeles on Feb. 23, 1978. From left: Lindsey Buckingham, Stevie Nicks, Christine McVie, Mick Fleetwood, and John McVie.

(Richard Drew / Associated Press)

How do artists feel about it?

Many artists depend on TikTok to reach fan bases and would lose a major marketing and creative tool.

“TikTok is a huge and useful platform for most artists — it works really well,” said Imogene Strauss, a creative director working on the rollout for Charli XCX’s album “Brat.” “We’re in the middle of a big album campaign now, it would be devastating for our plan if a ban or licensing dispute happened. It’s good promotion, and it sucks for those that aren’t there anymore. But artists should also be getting paid. I’m not saying TikTok is fundamentally good, but the only people suffering here are the artists.”

“It’s kind of heartbreaking,” said Maddie Zahm, a singer-songwriter who had a major breakthrough on TikTok with her song “Fat Funny Friend.” “I’m friends with people that have worked really hard to write songs, and given that TikTok kind of runs the music industry, it sucks to tell them they’re not allowed to be on it. I expected there to be a new thing someday, I just didn’t expect this limbo.”

Others are quietly relieved they may not have to constantly perform for an app with diminishing returns for exposure.

“it is weird to be like ‘I wrote this powerful, vulnerable thing, and now I have to package it and perform emotion by sitting in my car and crying so that people will see me and listen,’” said singer Zolita. “It’s really interesting what you’ve got to do to get people to pay attention there. It’s hard to keep your sanity when it’s such a numbers game, and to be at the mercy of this platform when you’re promoting art.”

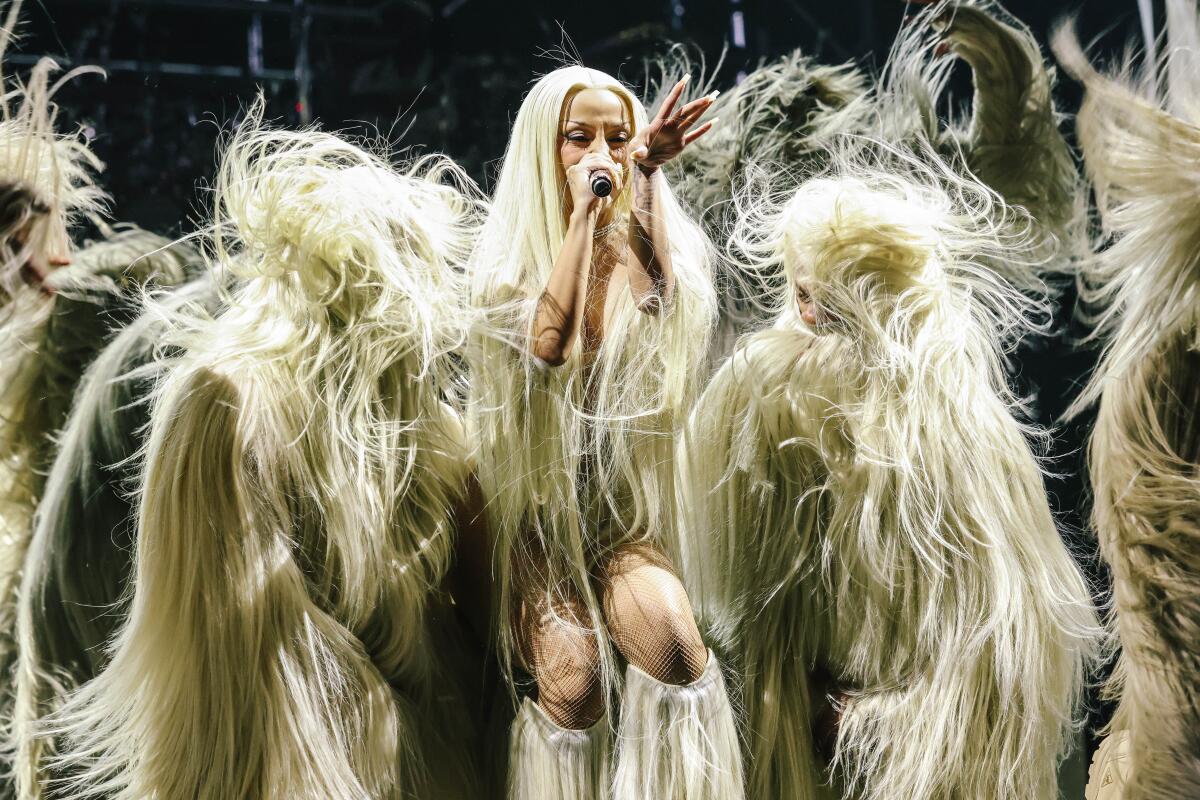

Doja Cat headlines at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival on April 14 in Indio.

(Dania Maxwell / Los Angeles Times)

How will artists connect with fans if TikTok is banned?

“Artists should have unlearned having one platform being their main vehicle,” Columbia’s Flanagan said. “I knew people with massive Instagram audiences, and suddenly they change their algorithm and you can’t reach your followers. You have to make sure you have email, texting, Discord, Substack, all of that. Trends change so quickly, you need to be able to transfer your superfans to other platforms.”

Engagement from young audiences may already be slipping. In a Wall Street Journal report, mobile analytics firm Data.ai cited a 9% decline in average monthly American users on TikTok from 18-24 between 2022-2023

Others are focusing on more old-fashioned ways of connecting with audiences.

“I feel like touring is going to be an even bigger thing,” said artist Hemlocke Springs, who is opening for Doja Cat’s European arena tour. “I’m going into these Doja shows assuming no one knows me, and the more I lean on that, the more it lights a fire under me.”