Panto season is just about over and we’ve booed the baddies to our hearts’ content. But as the curtain falls on this distinctive sound until next Christmas, should we consider jeering more often? This is not a call for more of the antisocial chomping, swiping, swilling, peeing or worse that have made the headlines recently. It is an inquiry into the old – and possibly fine – tradition of collective dissent, expressed in the once almighty audience “boo”.

In pantomime, such protests have little sting – they are so infused with obliging bonhomie that we may as well be clapping. The more straight-faced, incendiary boo of displeasure has been all but silenced, bar lone tuts or harrumphs. But for centuries, theatregoing etiquette allowed for heckles and hisses alongside cheers and whistles, all permissible within the great debating chamber of drama.

Booing is still present in the realms of standup, music concerts, opera, even the Cannes film festival – and it feels fairly shocking when it occurs. This might be because the material is deemed scrappy, or the action on stage offensive. But boos can also be a sign of intolerance. Robert Hastie, artistic director of Sheffield Theatres, has seen it in opera. “It’s usually because the performer or performance has deigned to present an alternative to an established, canonical interpretation. I know an actor [of colour] who worked in Germany, in a Wagner opera, who was booed.”

From ancient Greece onwards, a powerful exchange between performer and spectator has been a cornerstone of the theatre experience. Pamela Jikiemi, head of film, TV and audio at Rada, notes that when plays were the main form of entertainment, they were often so long that social interaction became inevitable: “Audiences were encouraged to respond.”

This was the case with Shakespeare’s audiences, adds Farah Karim-Cooper, a professor of Shakespeare studies at King’s College London. A Shakespeare play, staged at the Globe in the Elizabethan era, was a convivial event and the auditorium a genially noisy place. As a relatively new industry, it had no prevailing social code. “These big, epic commercial plays,” says Karim-Cooper, “were a brand new thing and an experiment. Nobody really knew how to respond to them.”

While spectators often dished out thunderous applause, they did not hold back on conspicuous disapproval either, albeit without open hostility. Repertory companies, performing a different play each night, were led by audience reaction: “If the audience didn’t respond well to a new play,” says Karim-Cooper, “you wouldn’t see that play again. Programming was rooted in audience taste because otherwise they wouldn’t make any money.”

This was not dissimilar to 19th-century music hall, when “the audience was king”, says Simon Sladen, senior curator of theatre at the V&A, and chair of the UK Pantomime Association. Cheers or jeers became a litmus test, essential for how managers shaped a billing. “If you wanted to get the person off the stage, you’d boo – and people would have been throwing stuff too. If you wanted them on, you’d cheer for longer.”

But as shows were given longer runs, decisions were no longer so predicated on the immediacy of audience reaction. Technological developments, including the advent of electricity and improved lighting, led the audience to quieten down. “In Shakespeare’s theatre, everything was lit so the audience was visible,” says Karim-Cooper. But as viewers were put in the dark, the dynamic changed. “It keeps audiences quiet. It might have trained them to be more reverent.”

So we arrive at modern audiences, some more willing to express dissatisfaction than others. Katerina Evangelatos – artistic director of the Athens Epidaurus festival, which celebrates ancient Greek drama – has witnessed audiences of up to 10,000 people venting their outrage at unconventional interpretations of canonical tragedies, loudly condemning them as sacrilegious.

The British-Tanzanian actor Lucian Msamati has had numerous first-hand experiences of booing, such as in Harare while performing with his Zimbabwe-based theatre company, Over the Edge. This was a case of playing to the wrong crowd, at the wrong venue, rather than any failure in performance. “It was our adaptation of the Complete Works of Shakespeare,” he says, “which the Reduced Shakespeare Company had made a huge hit. We were the first company on the African continent to get the rights to do it. We adapted it for five actors and put in local jokes.” But when his troupe took it to a music festival, and an audience that had been drinking all day, there was open hostility. “Within about 30 seconds, we were being booed and heckled. Things were being thrown at us! Eventually, we had to leave the stage.”

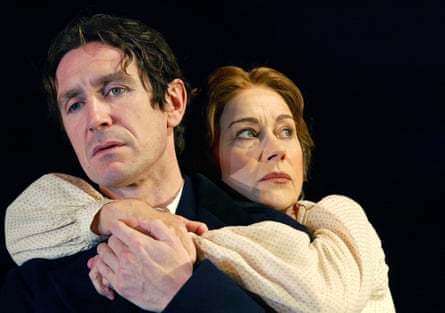

More puzzlingly, he remembers hearing booing at a curtain call for Mourning Becomes Electra, at the National Theatre in 2003, in which he starred alongside Helen Mirren and Paul McGann. “It was very audible one night and I was curious to know why they were booing because it’s so rare. Perhaps some audience members were thinking, ‘This is a great big show, with all these stars, and I’m not impressed – I’m going to express that.’ For someone to not walk out but make an effort to boo at the end tells its own story.”

If there is a usefulness to modern-day booing, it is in its affront to bourgeois decorum, which can lead to passive audiences, indifference and even dishonesty. Msamati, for one, does not resent viewers their honest if hostile response. In venues inhabited by a less traditional or more culturally diverse audience, there is often more voluble “dialogue” between actors and audiences. Msamati cites the uninhibited reactions of those watching the Bush theatre’s recent Red Pitch, and feels it is never a turn-off for an actor to hear loud, sometimes disapproving, exclamations when the room is so captivated by the drama that their disbelief is entirely suspended.

Although audiences may not be as outspoken as they once were, they have found other ways to express their displeasure. Actors report theatregoers reaching for their phones (or even, in the case of Andrew Scott’s Hamlet, a laptop) which might be a passive aggressive form of disapproval. They also speak of the aggressive nature of collective coughing. The most socially acceptable expression of dislike in the auditorium seems to be the walkout, sometimes en masse, which might amount to booing with one’s feet.

Boos, when there is a rare outbreak, can divide audiences. Sladen remembers a performance of Imagine This, a musical about the holocaust, set in the Warsaw ghetto, which closed early in 2008. Booing, he says, broke out during a scene in which characters put on a floor-show on their way to extermination. “That was the first time I’d ever been in an audience that was really booing the distasteful nature [of a show], particularly one of the songs in which a character did a razzle-dazzle musical number as they were being murdered. The booing was visceral and actually quite scary.”

But, he adds, there was a contingent who hushed their fellow audience members. “You had this weird audio soundtrack to the musical number – some people disapproving of what was happening on stage, some disapproving of the booing and trying to stop it. The clashing sounds became a statement of feeling.”

Perhaps it’s cathartic when we are encouraged to boo – and maybe this accounts for the enduring success of panto. But panto’s boos have evolved. While they are now purely rambunctious, once they held moral freight: the crowds were cheering for the good fairy and booing the villain, says Sladen, in what might have been an extreme display of the polarities of good and evil. “The audience’s vocal contribution encouraged the moral lesson to be learned. But then we get a shift into family entertainment, where it becomes a stock convention. Booing when a villain comes on helps to build a shared community. And if you speak to stage villains today, they feel the more boos they get, the more the audience likes them.”

It is also a sign, believes Hastie, that the audience has become delightfully absorbed in the action and stopped seeing the separation between character and actor. “I’ve experienced the best kind of booing, which is in a pantomime or a show for young people, where they are so immersed in the show they believe the fiction to be real, or they invest in the fiction like it’s reality.”

For Msamati, young people make the most astute and critical audiences, because they don’t hide their instinctive responses. “They can smell bullshit for miles,” says Msamati, “and they will express that.” Karim-Cooper agrees. One programme at the Globe offers free shows to children, many of whom have never been to the theatre before. She says their noise and their unfettered responses, both negative and positive, are the closest to an Elizabethan audience you’ll get. “The Globe has to gird its loins every time,” she says. “Nobody has trained them how to go to the theatre, and the space doesn’t train you how to be in it. It’s electrifying.”