In June 1982, moviegoers were charmed and terrified, respectively, by two of the most celebrated alien movies ever: Steven Spielberg’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and John Carpenter’s The Thing. Forty years later, we’re celebrating their legacies. Welcome to Alien Day.

Earlier this year, Marvel confirmed that the fourth issue of its ongoing Han Solo & Chewbacca comic, due out in July, would be a “Chewbacca-centric special issue” in which the Wookie would take the lead role, joined by guest star (and fellow Kashyyyk native) Krrsantan. It would be one of the few times in Star Wars history that Han’s constant sidekick would get top billing; the perpetual copilot would get a crack at the controls. Star Wars would finally let the Wookiee win.

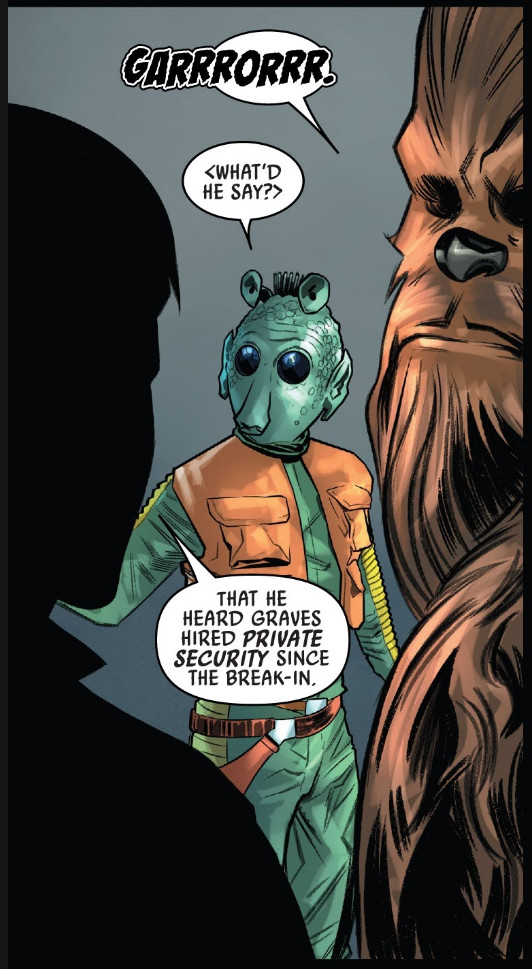

Except that even when Chewie temporarily seizes the spotlight next month, he won’t have the chance to speak for himself. Throughout the comic’s run, Chewbacca’s been restricted to roars and growls, as Star Wars tradition dictates—even when he’s with Han, who understands his bestie’s native tongue, Shyriiwook. The Rodian character Greedo, of “Han shot first” fame, has his Huttese words translated into Basic. (That’s Star Wars for English.) But Chewie has to have Han interpret, and as always, our window into the Wookiee’s deeper thoughts, feelings, and interior life is lost.

In muzzling Chewie, Han Solo & Chewbacca writer Marc Guggenheim is merely following the lead of decades of Star Wars stories—including a 2015 Chewbacca comic-book miniseries—which have only rarely clued audiences into what Wookiees were thinking. “I never really considered translating the Shyriiwook,” Guggenheim says via email. “It’s never translated in any of the TV shows or movies and I strive to avoid deviating from the conventions established in live action and animation whenever possible. Plus, I liked the challenge of doing a Chewie-centric issue all in Shyriiwook.”

This well-intentioned decision, however rewarding, is merely the latest in a long line of slights suffered by one of the few heroes who appears in all three Star Wars trilogies. The Rise of Skywalker rectified one notorious on-screen snub by giving Chewie the well-deserved medal he hadn’t received in Episode IV, but the sequel trilogy found new ways to get the big walking carpet out of the way. Whom does Leia hug after Han dies? Rey, whom she hardly knows. Who inherits the Millennium Falcon’s pilot’s seat? Poe Dameron, Lando Calrissian, and even Rey, who had almost no flight time. Who could forget Finn’s “You can understand that thing?”, or Luke’s complete lack of excitement at seeing his old friend? And that makeup medal? It wasn’t actually awarded to Chewbacca; it was Han’s hand-me-down.

This disrespect was par for the course. In the late 1990s, the pre-Disney architects of the now-decanonized Star Wars Expanded Universe decided to kill a character from the movies for the first time. Naturally, they chose Chewbacca. Chewie, Lucasfilm’s Leland Chee explained, was “a challenging character to write for” because “he can’t speak and just speaks in growls.” Instead of giving him a voice, a group of authors and editors dropped a moon on his head. Randy Stradley, the former Dark Horse editor who helped condemn the character to death, justified the decision by saying, “There have been very few stories in which Chewie’s presence, motivations, or desires have moved the plot ahead in a substantial way. He was the quintessential ‘supporting character.’” Chewie always plays second, third, or fourth fiddle. It’s his lot in life—and evidently in death.

Whether you weep for the Wookiee or not, there’s something emblematic about the second-class treatment the inescapable sci-fi franchise has afforded its most famous, most beloved, and most prominent nonhuman/nondroid character. Aliens on screen (and not just in Star Wars) are generally relegated to shallow, ancillary, and often antagonistic roles. Real aliens aren’t here to stick up for their fictional counterparts—unless the Department of Defense or NASA knows something we don’t—so I’ll advocate for them. Are we so self-centered, so insecure, and so small-minded that we can’t stand to see another species seize a sliver of the spotlight? Are we too parochial to suspend our disbelief and put ourselves in the place of fictional life that evolved elsewhere? When we do allow aliens ample screen time, must we insist that they be villains or, alternatively, look exactly like us? Here’s my plea: Let TV and movie extraterrestrials look like they aren’t from Earth. And let them play lead.

A few high-profile projects have followed that formula, with memorable results. This month marks the 40th anniversary of two seminal alien movies, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and The Thing. The two classics’ titular aliens sit at opposite ends of the sympathetic-character spectrum. Much of E.T. is shot and told from the extraterrestrial’s perspective; he’s peaceful and friendly, but he’s also distinctive, unsettling, and even (at first) sort of scary, as one might expect a totally unfamiliar life form to be. (Special-effects artist Carlo Rambaldi won Oscars both for designing the big-eyed, apparently pacifistic, phoning-home E.T. and for making the mechanical head effects for the nightmarish Xenomorph from Alien.)

Granted, E.T. speaks sparingly, we never learn his real name, and his pal on Earth, Elliott, is arguably the movie’s main protagonist. E.T., director Steven Spielberg said, was “never meant to be a movie about an extraterrestrial,” and the movie was filmed under the cover name A Boy’s Life. (Though the script refers to E.T. as “he,” so hey, he could’ve been the boy.) But there’s a reason it’s not called Elliott the Terrestrial. At worst, E.T. is a co-lead, like Neytiri from Avatar, Stitch from Lilo & Stitch, or a far less hostile Venom from Venom. The Thing, meanwhile, is a shape-shifting killer whose personality and non-murderous motivations we know nothing about. It’s a ruthless, lethal, and almost inexorable Other, along the lines of the Xenomorph, the Predator, or the Blob. (Or, for that matter, the genocidal supervillains from space who swarm the Marvel and DC universes, such as Thanos, Darkseid, and Galactus.)

Aliens make great antagonists, so I’m not suggesting that they stop being fodder for creature features. I’m just requesting that we slightly balance the scales. This week, my colleague Michael Baumann made a matrix of alien sidekick characters. He had plenty to choose from, but alien protagonists would make for a much smaller draft pool. You’ve got Goku, Superman, Klaatu, and the titular Doctor of Doctor Who, all of whom are humanoids who could pass for natives of Earth. There’s Thor, who’s technically an alien, though he’s more often described as a god. (He looks human, too, or as close to mortal manhood as Chris Hemsworth can come.) The “alien passing as human” category also includes characters who live on Earth undercover, a genre exemplified by Mork & Mindy, 3rd Rock From the Sun, Resident Alien, and The Man Who Fell to Earth (the novel, film, TV movie, and TV series). But how many aliens who actually look like aliens get to be the protagonists of their own franchises? Zim from Invader Zim? How about heroes? Abe from Oddworld? Ratchet from Ratchet & Clank? ALF? Optimus Prime? It’s not a long list.

Some of the reasons for that are practical: Exotic creatures on screen means more money spent on special effects or more time in makeup and prosthetics for actors. Real-life stories serve as source material for dramatized retellings, and we’re sorely lacking real-life aliens (or even alien signals) to make biopics about. Crafting a convincing alien—and an alien culture—requires creativity and worldbuilding that more mundane settings don’t. Plus, subtitles are sometimes a tough sell.

First and foremost, though, humans inherently respond to stories about their own kind, which is why alien leads are so scarce. The director of 2019 video game Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order, Stig Asmussen, said that while “Personally, I think it would be really cool to have an alien protagonist,” developer Respawn Entertainment ultimately “didn’t go with an alien race because we felt like, no pun intended, that would alienate a lot of people. We wanted to make sure that there was a real human connection to the character we have in the game.”

Because of that concern, alien-invasion or first-contact stories—like Arrival or Annihilation—tend to be presented from a human POV, and more often than not, encounters with E.T.s pose as opportunities for earthlings to learn something about themselves. It’s no surprise that stories told by humans, for humans, would be a bit humanocentric. Science fiction is littered with tales of human exceptionalism, in which we Earth dwellers are collectively too tenacious and plucky to be conquered, and too irrepressible and inquisitive not to boldly go. As a result, it always seems to fall to humans to take the lead. Nonhumans add galactic color at the local cantina or recreational lounge, but they’re far from view—or, at best, at the periphery of the frame—when it’s universe-saving time.

Thus, Star Wars civilizations rise and fall largely in response to the Skywalkers (humans) and their service of or opposition to Emperor Palpatine (human, believe it or not). The leader of the Guardians of the Galaxy is Peter Quill, the half-human who was raised on Earth. The commander who dictates the fate of all life in the Mass Effect universe is a human, Shepard. Martian Manhunter rarely leads the Justice League, though his powers dwarf those of frequent head honcho Batman. (The original Justice League’s only nonhuman-looking character is also the only one who hasn’t fronted a movie, provided The Flash actually comes out.) And the captains in every Star Trek series are human, save for Discovery Season 3’s Saru, a Kelpien who only kept the captain’s seat warm for Michael Burnham, the human who headlines the series.

Star Trek’s best-known extra-terrestrial, Spock, is not only a sidekick, but a half-human who looks human aside from his pointy ears and eyebrows. He also spends a lot of time wrestling with his human heritage. Meanwhile, Michael Dorn has been pitching a Worf show or movie for a decade, unsuccessfully so far. Maybe he’s struck out because his idea demands a less anthropocentric perspective; as he put it last year, “Instead of looking at the Klingon Empire from Starfleet, we look at Starfleet from the Klingon Empire.” For now he’ll have to settle for a cameo on Picard.

Historically, humans have been bad at depicting more than one race or gender of our own species on screen, so alien representation is hardly a top priority. For the right sci-fi story, though, the judicious addition of a well-drawn nonhuman can be crucial. When Halo 2 introduced a deuteragonist to the franchise in the Arbiter, the playable Covenant warrior held up a mirror to Master Chief’s actions, provided narrative and visual variety, and made the space-marines shooter more creatively rich and complex, contributing to two of the best campaigns in the series.

It’s not that we need a sequel to E.T. (The less said about the cursed concept that would have underpinned the proposed sequel to E.T., the better.) What we need is more media like E.T: movies, video games, and TV shows with the imagination and conviction to tell compelling stories while expanding the definition of fictional life as we know it. And while we’re dreaming up brand-new nonhumans, why not try to turn some overlooked extraterrestrials into stars from the stars? Give Martian Manhunter his own big-budget blockbuster. Let Worf be first on the call sheet in one of the 17 Star Trek series on Paramount+. (Only a slight exaggeration.) Let Liara T’Soni be the star of the next Mass Effect sequel. And please, somebody get Chewbacca some subtitles.

I started this piece by giving Star Wars grief for being speciesist—not for the first time—so I’ll end by acknowledging a promising sign. No Star Wars movie or TV series to date has centered on a nonhuman character (unless we’re counting the animated Star Wars: Ewoks). That will change next year, when Ahsoka debuts on Disney+. The series will star the eponymous ex-apprentice of Anakin Skywalker, Ahsoka Tano, a Togruta (played by Rosario Dawson). It will also feature the Chiss Grand Admiral Thrawn, whom Variety reported would be the series’ “main villain.” Picture a hero who has head-tails, and a cerebral baddie with blue skin and red eyes. With Ahsoka and Thrawn as the leads and humans Ezra Bridger and Sabine Wren as supporting characters, Ahsoka could topple protagonist tradition and emerge as a landmark in nonhuman stardom in Star Wars. And if it’s successful, the series could pave a path for future fictional aliens outside of Star Wars to prove that they won’t alienate audiences.

As for Guggenheim, his work will soon be appearing in a new Marvel comic about a Star Wars alien who does speak Basic, albeit with strange syntax: Yoda. Maybe our pro-Earthling and pro-humanoid biases are being broken down. Space is so vast that there’s no way for humans to meet most (or, perhaps, any) existing aliens in the flesh (or whatever they have in place of flesh). For the foreseeable future, then, life from outside earth exists only in our imaginations—and, sometimes, our screens. Here’s hoping it finds a way.