Shared from Culture | The Guardian

“It means something brand new, never before seen, hasn’t been put on a map yet,” says Mark Wahlberg to his co-star Tom Holland in a promo clip explaining the title of their new movie, Uncharted. “And that’s what this movie is,” Holland agrees. Well … even without seeing Uncharted, we all know that’s not quite true. For one thing, it is adapted from a popular video game series, but also, let’s admit, in movie terms, this territory is actually pretty well charted. The treasure-hunt movie is now a genre, usually involving a couple of adventurers thrown into a globe-trotting quest for a highly valuable artefact, pursued by dangerous rivals, hostile natives and so on.

This terrain has been mapped over the past 40 years by the likes of Indiana Jones, Romancing the Stone, The Mummy, National Treasure, Tomb Raider, the other Tomb Raider. Just last summer we had Disney’s Jungle Cruise – with Dwayne Johnson and Emily Blunt questing up the Amazon.

Next month we will be getting The Lost City, with Sandra Bullock and Channing Tatum questing in Central America. A fifth instalment of Indiana Jones is halfway through shooting.

Clearly, this is a formula that works. But it is also a narrative with a legacy. There’s no way round it: these are stories of white people travelling to lands populated by non-white people and stealing their stuff. As anyone who has visited a European or American museum in the past century will know, this is not pure fiction. In real life, however, the direction of travel is now more in the opposite direction. Institutions in Europe and the US have begun returning looted artefacts, such as the Benin Bronzes, which were taken from Nigeria by the British in 1897. Last year, the Belgian government agreed to return some 2,000 “stolen” artefacts to Congo, and Unesco urged the British Museum to return the Parthenon (AKA Elgin) marbles to Greece.

Uncharted is primarily unchallenging popcorn fare, but as with so many treasure-hunt movies, its connections to the real history of colonial plunder are barely disguised. The treasure in question here is that of Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, who led an expedition that circumnavigated the globe in the name of the Spanish empire 500 years ago. According to the film, his booty-laden ships are still out there, somewhere in the Philippines. (There is little discussion about where Magellan might have acquired such riches, or who its rightful owners might be.) Holland’s character is Nathan Drake, son of an American archaeologist and self-proclaimed descendent of Francis Drake, England’s own 16th-century imperialist plunderer. His arch-rival in the race to find Magellan’s treasure is a descendant of the Spanish family that originally funded Magellan. So not such a “brand new” story after all.

So many of these movies refer to history for their myths and MacGuffins, particularly the British empire. In Jungle Cruise, Emily Blunt is a posh, surprisingly athletic English botanist in the 1910s. Tomb Raider’s Lara Croft is of a similar pedigree: the well-educated daughter of a wealthy, aristocratic British archaeologist. In The Mummy movies, Rachel Weisz plays a bookish (but surprisingly athletic) 1920s Egyptologist named Evelyn Carnahan. She was modelled on Evelyn Beauchamp, daughter of Lord Carnarvon, financier of Howard Carter’s Egypt excavations that discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb.

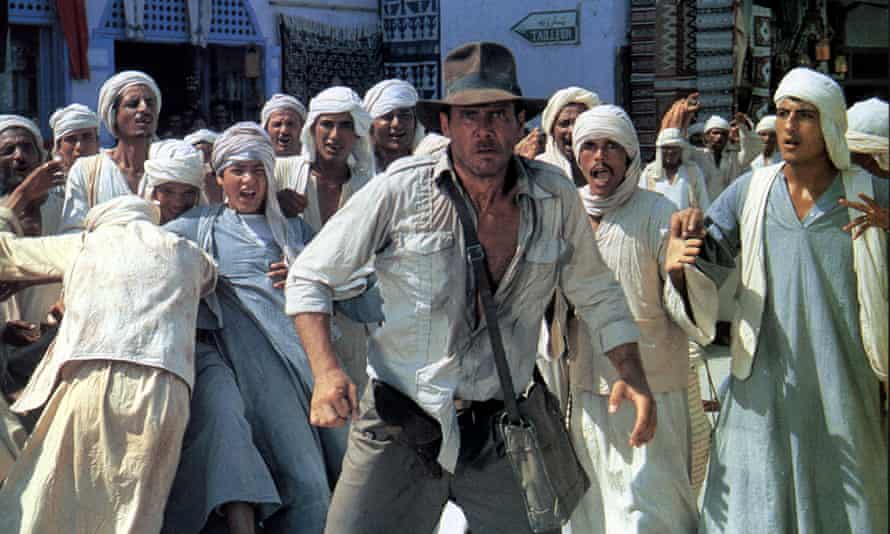

Rather than actual history, though, the real origins of this genre lie in movie history, and in particular, that Magellan of archaeological adventuring, Indiana Jones. As notes from a 1981 brainstorming session between George Lucas, Steven Spielberg and Lawrence Kasdan revealed, they were chiefly inspired by the movies they grew up on, such as King Kong, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and the thrilling Republic serials of the 1940s and 50s. Also mentioned are Ripley’s Believe It Or Not, Disneyland rides and pseudoscientific books such as Erich von Daniken’s Chariots of the Gods. “I don’t think they even knew the name of a single real-life historical archaeologist,” says Justin Jacobs, history professor at American University and author of Indiana Jones in History. “It’s all recycling of previous pop culture. There’s zero historical research in there.”

Looking at the anachronisms and casual racism of the Indiana Jones movies, this comes as no surprise. In 1984’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, for example, the film-makers took the 1930s Indian setting as licence to lay out an all-you-can eat buffet of Orientalist stereotypes. Literally so in the maharajah’s feast scene, where live snakes, eyeball soup, giant beetles and chilled monkey brains are on the menu (none of which have anything to do with Indian cuisine). Further afield, the movie peddles a brown-skinned death cult that rips out people’s hearts, kidnaps white women and enslaves children – until Indy turns up to white-saviour everyone.

Consciously or not, these movies mirror Europe’s real-life colonial enterprises. Lucas initially imagined Jones as a kind of “outlaw archeologist”, for example, but quickly realised his hero would need a veneer of academic legitimacy to justify his looting, hence his catchphrase, “That belongs in a museum!” The real-life European looters of the 19th century used similar justifications, says Jacobs: “Basically, it was: ‘We’re going out in the name of science. We’re going to rescue evidence of grand, glorious civilisations that once existed in the distant past. You guys don’t care about this stuff any more. We’re rescuing it, preserving it, we’ll study it, put it on display, and then educate the world.’”

The whole exercise was underpinned by essentially racist assumptions. Foreign artefacts were often valued solely in terms of their relevance to European history. Superior non-white craftsmanship was invariably taken as evidence of some hidden European influence. Or even extraterrestrial influence in the case of Von Daniken’s theories about central American civilisations (Indiana Jones part four, The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, agreed). The decline of formerly great civilisations was often attributed to racial intermixing diluting some original white, empire-building ancestry.

The colonial powers of Europe were often in competition. Italian explorer Giovanni Belzoni, for example, became a national celebrity when he shipped a huge bust of Ramesses II from Egypt to London in 1818, succeeding where Napoleon’s troops had failed (it is still on display in the British Museum). “It wasn’t so much a case of: ‘That belongs in a museum’ as, ‘That belongs inourmuseum.’” says Jacobs.

You don’t have to look far to explain how Indiana Jones spawned a whole genre. Raiders of the Lost Ark was the highest-grossing movie worldwide in 1981. Its three sequels were equally huge. Joining Temple of Doom in the box office top 10 in 1984 was another treasure-hunt smash: Romancing the Stone, which at least charted some new territory, in that neither Kathleen Turner nor Michael Douglas were posh, British, or even interested in archaeology. Still, they had a map and were on the hunt for a fabled emerald. When they eventually found it, did they donate it to a responsible Colombian cultural institution? Of course not. Douglas sold it and bought a yacht.

As well as replicating Indiana Jones’s profitability and casual stereotyping, Romancing the Stone and its sequel, The Jewel of the Nile, cemented another trope of the treasure-hunt genre: white women find these kinds of adventures rather liberating and transformative. Turner’s literary urbanite is initially squeamish at Colombia’s people, animals, weather etc. Then Douglas chops off her high heels with a machete and she’s free! Many others have followed in her flat-heeled footsteps. By the looks of it, that includes Sandra Bullock in The Lost City: she plays another lonely writer “thrust into an epic jungle adventure” – along with Channing Tatum’s equally useless male model.

There have been a few attempts to take this kind of explorer material seriously. Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo and Aguirre, the Wrath Of God, say. Or, more recently, James Gray’s The Lost City of Z, based on real-life British explorer Percy Fawcett, who spent nearly 20 years searching for a mythical Amazonian city (coincidentally co-starring Tom Holland). Ciro Guerra’s Embrace of The Serpent offered a more bracing counter-narrative, viewing two different white men’s Amazon expeditions through the eyes of their indigenous guide. Also noteworthy is the scene in Marvel’s Black Panther where Michael B Jordan’s Killmonger forcibly repossesses an African artefact from a British museum. “How do you think your ancestors got these?” he asks.

Is it possible to retool these creaky narratives for our more culturally enlightened age? Possibly. Disney’s Jungle Cruise managed partially to disguise its own problematic origins. The original Disneyland ride took passengers on a mock British colonial vessel through a mash-up of “exotic” Asian, African and South American landscapes, complete with racist caricatures such as “Trader Sam”, a grass-skirted animatronic cannibal holding up a shrunken head. Sam was quietly removed from the ride in preparation for the movie. In Jungle Cruise, the sought-after treasure is not an indigenous artefact but a medicinal tree at the heart of the Amazon, first sought by Spanish conquistadors. Blunt’s liberated heroine (she even wears trousers) seeks the tree in order to help treat first world war soldiers. Rather than faceless enemies, the indigenous jungle-dwellers are treated respectfully (Trader Sam is a woman, and not a cannibal), and the villains of the piece are the ghosts of the Spanish conquistadors, in league with the Germans.

Uncharted navigates its own clumsy course through these waters, bizarrely involving two women of colour (and no Filipinos), although its treasure-hunters do not even pretend to have philanthropic or intellectual motivations; they just want the loot. Let’s see how The Lost City and the fifth Indiana Jones fare. The Lost City’s trailer features no discernible locals. Indiana Jones’s story reportedly involves Nazis and the space race, which suggests it also dodges issues of foreign engagement. Almost certainly this will be the last of the series – Harrison Ford turns 80 this year – if not the end of the treasure-hunt movie era, although perhaps it’s time. There’s a moment in The Last Crusade when Indy tells the panama-hatted villain stealing his golden artefact: “That belongs in a museum!” The villain replies: “So do you.”

Uncharted is released in the UK on 18 February.

Images and Article from Culture | The Guardian