Madame Web’s poor initial performance at the box office suggests that few people want to see it in a theater, let alone talk about it sight unseen. But there’s one aspect of it we should talk about anyway, because it’s so wild. Madame Web is a rarity in modern superhero cinema: a movie your friends might think you were making up if you described it to them without embellishment. Ironically, this makes it entirely faithful to the era of comic books it’s adapting. Not only does the comic book version of protagonist Cassandra Webb have a suite of powers and stories behind her that’s so confounding, I cannot fathom how anyone thought they’d make for a coherent movie, it also features a trio of other Spider-Women with origins that beggar belief.

All these women make the Peter Parker/Miles Morales origin of “bitten by a radioactive spider” appear mundane by comparison, the comic book version of a baking-soda volcano at a middle school science fair. Here’s the rundown on where this trio came from, according to Marvel Comics canon.

Aña Corazón

The early 2000s was a rich period in white comics writers and artists concocting marginalized characters, and Aña Corazón (initially named “Araña,” the Spanish word for “spider”) was one of them. Aña’s origin is some real body-horror magician shit. The story involves a war between two secret magical clans that she’s caught between. Eventually, she’s imbued with a magic tattoo that gives her a gross blue carapace she can summon at will. It honestly kind of rules.

But with no steady creative champion writing her stories, Aña bounced throughout the Spider-Man family of comic books, her powers and backstory getting slightly reworked each time. (You will not notice a carapace in the Madame Web version, where she’s played by Isabela Merced. But you can see it in her very brief appearance in Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, above: Standing in a group of other shocked Spider-People, she responds to Miles’ attempted escape by summoning her armor.) For a while, Aña even continued to superhero without powers. These days, she goes by Spider-Girl (she’s one of many who do) and has a much more traditional suite of spider-related powers.

Mattie Franklin

Image: John Byrne, Rafael Kayanan/Marvel Comics

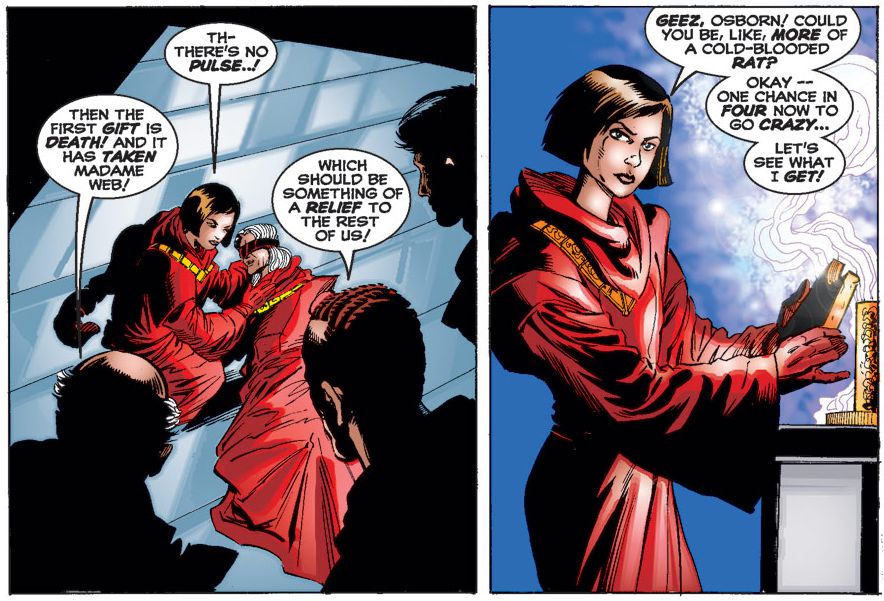

Mattie Franklin (played in Madame Web by Celeste O’Connor) has what’s perhaps the wildest origin of the three women here, stemming from one of the last in a very long list of terrible decisions Marvel made in ’90s Spider-Man comics. In a climactic story preceding a soft reboot, Norman Osborn, the Green Goblin, enacts a convoluted occult ritual that was supposed to give him Spider-Man’s powers. Instead, Mattie gets them, as readers found out in a big twist where Peter Parker is shown as not being Spider-Man for his comic’s big 1999 relaunch.

Like all big, shocking shake-ups in superhero comics, this one was undone pretty quickly, and Mattie became yet another Spider-Woman who comes and goes as writers and artists reinvent her. Lately, she’s gotten herself a set of those robot spider-arms, the same sort the baffling villain Ezekiel Sims sees in Madame Web via muddy future-vision. They’re pretty neat.

Julia Carpenter

Image: Roy Thomas, Dann Thomas, John Czop/Marvel Comics

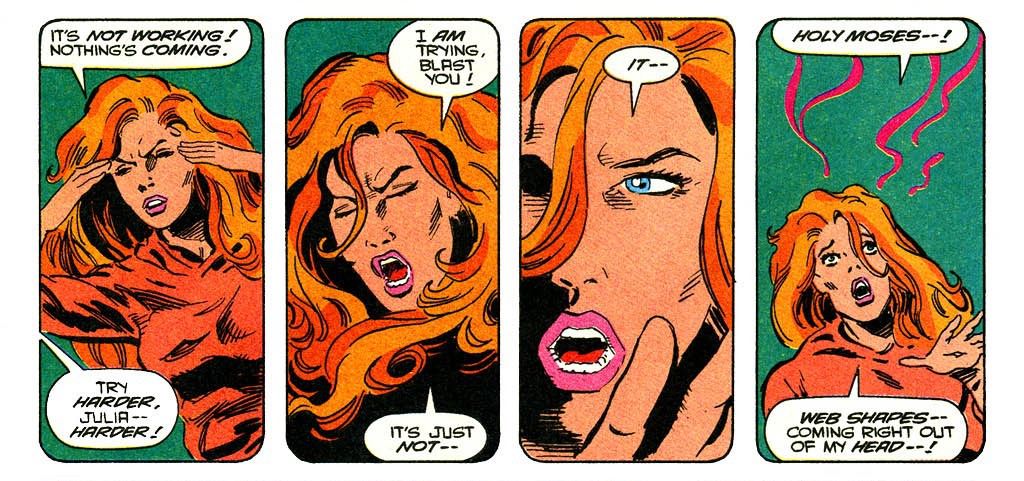

The thing you have to understand about the Julia Carpenter version of Spider-Woman is that she barely makes sense as a Spider-person. Her most famous adaptation before Madame Web (where she’s called Julia Cornwall, and played by Sydney Sweeney) was in the ’90s Iron Man animated series, where she almost never crawled on a single wall. Also, whether she could spin webs (and how) varied from episode to episode.

Her comic book origin has more in common with a ’70s spy thriller than anything Peter Parker got up to: She’s unknowingly given powers by a government think tank, then conscripted into a group of superhuman G-Men called Freedom Force. In spite of having the coolest costume (arguably a direct inspiration for Spider-Man’s famous black symbiote suit), no one ever knew what to do with Julia Carpenter, which probably explains why the “powers and abilities” section of her wiki is so damn confounding.

Why is Madame Web so bad?

Image: Fiona Avery, Mark Brooks/Marvel Comics

So given all this weird, complicated backstory, given so much colorful and exciting nonsense to draw on, why does Madame Web defang (or in this case, de-chelicerae?) its young heroines by limiting their hero identities to a single recurring nightmare scene? While most of this backstory wouldn’t have fit into the larger Spider-Man universe Sony is building, Madame Web is intended as more of a stand-alone film, with minimal connections to the SSU. That could have given director S.J. Clarkson and the four credited screenwriters a lot of freedom to include at least a hint of some of the stories that differentiate Madame Web’s Spider-Women from each other.

But since we don’t really get origin stories for these three at all in the movie — they don’t acquire their powers or costumes in this story, they never get to become heroes, and the whole narrative plays out half as a Madame Web origin story, half as a prequel for a movie that we can’t imagine will ever get made — there’s no room for any of that kind of color or detail.

It’s hard to imagine some of this material playing on screen — the magical spider-empowering ritual, the big team backstory featuring even more superheroes who this movie isn’t concerned with at all, and so forth. And the small origins we do get in the movie — a kid whose dad got deported, a neglected “poor little rich girl” type, a literal redheaded stepchild — are much more in keeping with the modern trend toward “realistic” superhero narratives.

It’s just a bit of a shame considering how similar those realistic narratives look, compared to the much more diverse and eye-popping narratives the print versions of these heroines came from. Oh well; we’ll always have Marvel back issues to go back to if we want the body-horror-and-magic version of the story.