In the post-Marvel Cinematic Universe era, it’s hard to find a savvy pop culture maven who can’t define “continuity,” whether they’re talking about comics, movies, TV, or video games. To me, as a lifelong superhero comics fan, it is most prominently the idea that a couple of 60- to 90-year-old story settings are not merely interconnected, but contiguous. That they’re not just built on dozens of disconnected stories happening in the same reality, but that every new story should cohere with what came before.

There’s more than one way to shepherd a massive, multigenerational continuity, and frankly, I find such attempts fascinating. I collect them like glass orbs to ponder. I study them like pinned moths. And every single one of them reveals the same eternal conflict: a constant, straining tension between the ideal of the story and the reality of telling it.

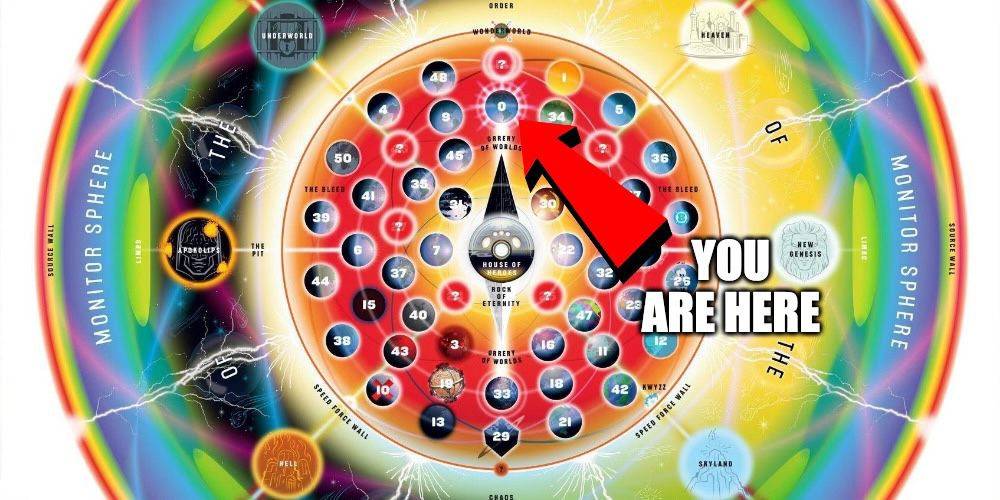

DC Comics has developed a custom of periodically restarting its timeline, once it becomes too much to ask fans to catch up on decades’ worth of storylines of wildly differing quality. Marvel is a single timeline of densely packed retroactive changes surrounded by a snarl of parallel earths and alternate timelines — because, yeah, that one gray-canon setting where Wolverine was hella old slapped extremely hard, and we’d like to see more stories there in the future. Hypertime and the Marvel No-Prize are exercises in creating Watsonian explanations for the Doylist reality that sometimes comics creators make things that break continuity, whether accidentally, or on purpose because it made an individual story better.

Rigid continuity does not come naturally to collaborative storytelling, and each of these approaches is a tacit acknowledgment of that cold, hard fact — because if things were otherwise, we wouldn’t need an approach in the first place. Now, if you ask me, this is not a hot take. But every time I talk about how continuity not only shouldn’t matter but already doesn’t, it seems to make people mad.

So here we are

The most common comeback I hear is: But if you don’t have consistent continuity, nobody’s going to be able to get invested in the story.

Graphic: Susana Polo/Polygon | Source image: DC Comics

And it’s worth being clear that when I say that “continuity doesn’t actually matter that much,” I’m not speaking about contained, individual works. Or at least, not the structured, narrative-based art that we see in most (but not all!) Western cinema, television, literature, and comics (and many video games). If somebody wants to tell a story that makes narrative sense, that story benefits from making narrative sense.

I’m talking about collaboratively told, long-running, wide-ranging interconnected and contiguous stories built from the kinds of contained, individual works mentioned above, which are not expected to come from the same creators every time. Marketing speak calls these “franchises.” You know them as the DC Comics universe, the Marvel Comics universe, the MCU, Star Wars, and others.

If, understanding that, you’re still opening your mouth to protest that nobody would like DC or Marvel if they didn’t have the promise of consistent continuity, I am grabbing your lapels. My eyes are bugging out. My sibling in Christ, I am begging you, do you know the story of King Arthur and the Lady of the Lake? Of Persephone and Hades? Of Robin Hood’s friend Little John?

That was a trick question! No you don’t!

Image: EMI Films

You don’t, because there is no “the story” for any of those. They’re all legends born of oral tradition and popular writing from eras and places in which authorship was a very different idea, if it was considered at all. They’re stories that were told over and over by so many tellers, and to so many audiences, that there’s no meaningful legitimacy to any individual telling. Was the Lady of the Lake Lancelot’s guardian, or Excalibur’s? Was Persephone pursued by Hades, or by Zeus? Was Little John among Robin Hood’s smartest companions, or his dumbest? The answer to all these questions is: “Which version of the story are we talking about?”

Any version of these stories that you know was cobbled together from the best bits of every version of “the story” that came before. The lack of a single “canon version” or “continuity” to Arthurian legend, Greek mythology, or Robin Hood hasn’t kept the stories under those umbrellas from being widely known hundreds and thousands of years after they were first told.

But it’s not caveman times anymore! somebody is typing into a comment box. Today we can record narrative art and make it available for the entire human race (or at least the chunk who speaks the language in which it was made)! Later stories can be consistent with previous ones in a way that was unreasonable in ancient times — we’re not painting Spider-Man on a fucking cave wall these days.

And OK, OK. I’m letting go of your lapels. (I just have big feelings about the parallels between collaborative franchise storytelling and oral traditions. Sorry.) But it needs to be pointed out that having the ability to fix a pin in a single version of a story, like a butterfly in a box, hasn’t stopped singular great narrative works from becoming multigenerational, collaborative, long-form projects. Everyone writing Spider-Man comics today is cobbling together their personal version of the best bits of the Spider-Man comics, shows, movies, and games that came before — and deemphasizing the rest. And so are the folks making The Acolyte, or Star Trek: Prodigy, or Captain America: Brave New World, or next month’s issue of Action Comics, or any story with Sherlock Holmes in it. And so is anyone who has ever written fanfiction, which is just the name that a subset of folk art goes by when it’s living under intellectual property law.

Our most enduring stories didn’t need consistent continuity to remain compelling today, and there’s no technological advance — from the movable-type printing press to the internet — that successfully rendered that near-infinite potential for variation down to a single accepted version. Anyone arguing to the contrary is arguing against thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of years of human history. In fact, I and many others who actually make these stories would argue that a lack of strict continuity is what allows these ideas to stay relevant even in the present.

And that’s equally true for superhero continuity

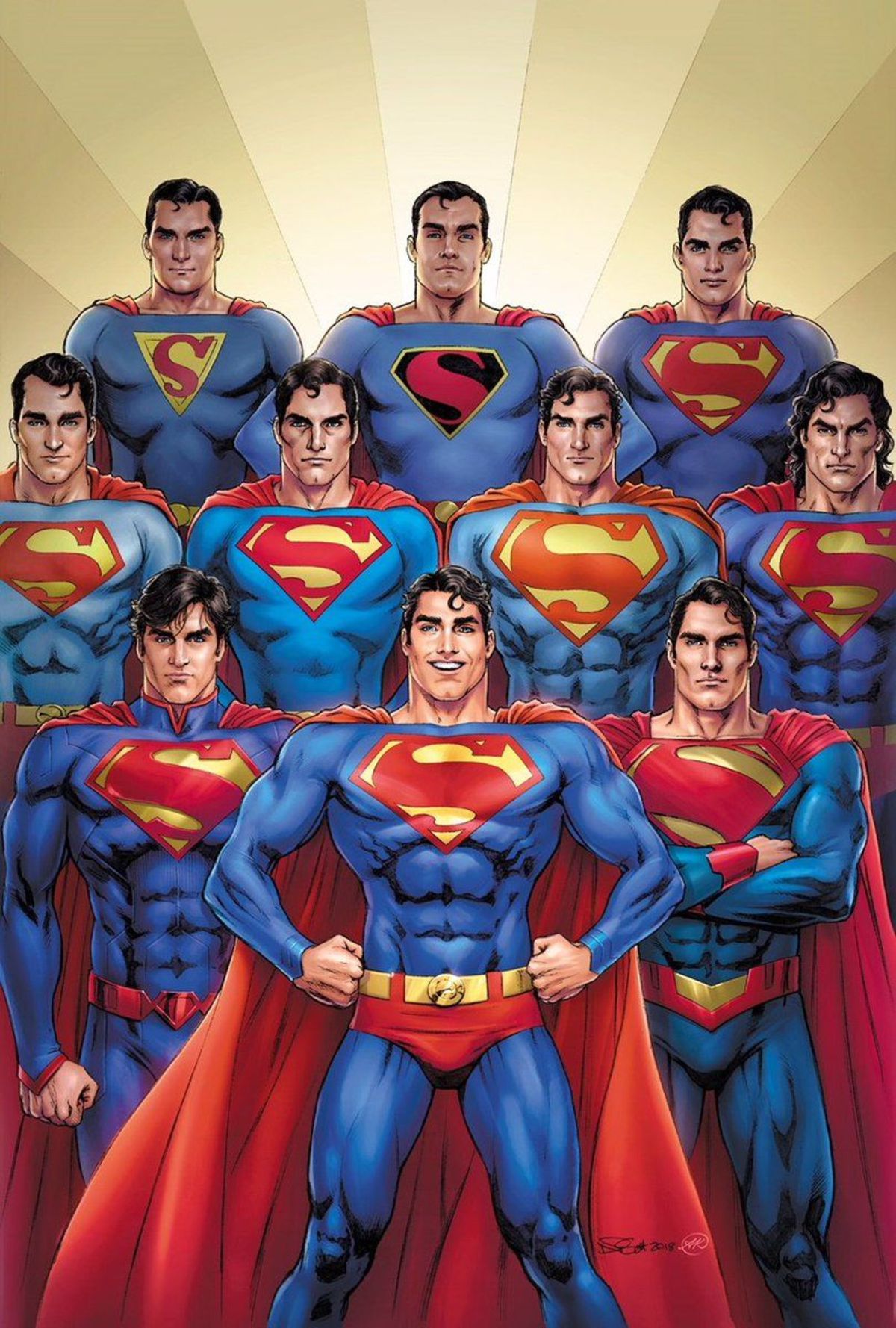

Image: Nicola Scott/DC Comics

Reboots, retcons, alternate universes, and Hypertime — these are the methods that modern franchise creators use to tell stories that break continuity, because they want to make their story better. And it’s not meaningfully different from a storyteller in oral or folk traditions fitting their telling to their audience. The more you dig into any given long-running and popular comic book superhero, or the details of a major Star Trek species, or basically any B-tier Star Wars concept, you’ll find people making it up as they go along — and find those who come after them cobbling together the best bits to move forward. The audience doesn’t need to know every version of Robin Hood’s story to know Robin Hood, and it shouldn’t need to know every version of Wolverine’s story to know Wolverine.

But Susana, you’re saying, I just want to read a Wolverine story and have it feel like ‘a Wolverine story.’

And I’m holding your hand gently when I say, My sibling in Christ, you think I don’t have a favorite kind of Batman story? Your idea of what feels like ‘a Wolverine story’ was defined by an aggregate of different Wolverine stories to begin with. There is no ‘the story’ of Batman or Wolverine. There’s just the one we like best.

A few years ago, Wolverine came back from the dead, and his new superpower was that his claws could get really hot. Nobody was at all bothered that a new X-Men writer took over five minutes later and, without textual explanation, Wolverine’s hot claws never appeared again. It’s easy to love strict continuity when it’s a version of the story that you like — but you’ll be begging for it to change when it’s something you think is dumb.

So when I say that continuity shouldn’t matter, I mean that, as a Batman fan, it’s in my interest for there to be lots of different versions of Batman — so that the versions of him that best fit the moment can be offered as a fit for the moment, so that there will keep being more Batman stories.

And when I say that continuity already doesn’t matter, what I mean is that that’s already happened. It’s currently happening. My favorite version of Batman contains elements invented by comics creators in the 1930s and ’40s, elements cribbed directly from Batman (1966) and Batman: The Animated Series, and the particular inclinations of a specific collection of Batman writers working in the 1990s.

Rigid continuity does not come naturally to collaborative storytelling. And that’s OK, because those soft spaces in the continuity of our modern multigenerational mythologies allow them to be multigenerational in the first place. History shows us that you can’t make a 50-year-old, or 25-year old, or arguably even 15-year-old work of collaborative storytelling without breaking a few — or many — canonical eggs. That’s not an accident, or a plot hole, or a cop-out. It’s just how you make a good fucking omelet.