As an internationally renowned director, Brazilian filmmaker Kleber Mendonça Filho is, in a manner of speaking, a citizen of the world: Regularly premiering films at Cannes, frequently traveling to festivals elsewhere in Europe, Australia, and the United States.

But anyone who knows Filho understands his heart is and always will be in Recife, in the northeastern state of Pernambuco. He was born there; he grew up in the city center and his love of cinema was nurtured in Recife’s old movie palaces. His attachment to the place emerges in Filho’s documentary Pictures of Ghosts (Retratos Fantasmas), Brazil’s official entry for Best International Film at the Academy Awards. In addition to that Oscar category, it’s in contention for Best Documentary Feature.

Director Kleber Mendonça Filho

Courtesy of Victor Jucá

Filho says Portraits of Ghosts “was not planned, but films work in strange ways.” The spark, as much as anything, was his move to a new house in Recife, which involved leaving behind a dwelling in Recife’s downtown that contained many memories for him.

“That got me thinking and feeling about the place where we lived, where I lived most of my life,” he explains. He kept coming upon a personal archive of video he had recorded while shooting some of his previous narrative films within those very walls. “I had shots in the apartment, and I thought, this should be in the documentary, in a strange way.”

The people – as well as dogs and cats – preserved in that archival video are not the only “ghosts” referred to in the title. The film powerfully recalls the grand movie theaters of central Recife which formed such a rich part of the filmmaker’s experience, and the collective memory of the city. The São Luiz cinema still exists, but many others, alas, have been consigned to realm of phantasm.

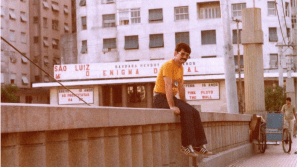

Kleber Mendonça Filho outside the São Luiz cinema in Recife

Courtesy of IDFA

“I remember very young going into the Art Palácio, for example, or the Veneza. I remember this one time I went to see The Witches of Eastwick at the Veneza,” he recalls. “I was alone. It was a Friday, about 6 p.m., and I went to the lobby where you wait for the next show. And I was sitting on the sofa, and I could hear John Williams’s music. It was coming very loud down the stairs, and I thought, ‘Wow, this is a cinema.’ And inside there is a kind of a fantasy horror film being screened and, and this amazing music coming down the stairs and into the hall. And it was a great feeling.”

Over three decades ago, Filho’s first film, a documentary short, focused on the projectionist at the Art Palácio, Alexandre Moura. Mr. Alexandre, as he was known, was sort of like a captain of an aging vessel, piloting the ship from the projection booth as the “passengers” below cruised on waves of cinema.

“The place was completely original,” Filho says of the Art Palácio. “It was untouched. So, it was the same cinema from 1940, which is quite rare. It did feel like you were in a hotel or on an old ship, you know? Not only an old ship, but a ship that is being prepped to be sunk, which is even eerier, because you look at all of that and you see it’s going to be destroyed.”

(Filho says he’s thinking of making a separate film just about the Art Palácio’s curious Nazi connections; the documentary explains the movie house was originally constructed under the direction of Nazi propaganda chief Josef Goebbles).

Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood, 1977.

HUM Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Movies have always been escapist entertainment. The screen palaces of Recife, just like the glorious temples of cinema in the U.S. — Grauman’s Chinese in Hollywood, the Fox Theatre in Atlanta, the Loew’s in Jersey City, N.J., among them — were escapist in and of themselves, places that, through their grandeur, transported people from their ordinary lives.

“They’re very strong pieces of artistic expression through architecture, and then architecture merges with whatever they’re showing [on screen],” Filho observes. “Even if you don’t think about architecture — even if you don’t even know what the word is — you think this is such a strange and interesting place, and the reactions of first timers going in, it’s just priceless.”

‘Pictures of Ghosts’

Cinemascópio

Pictures of Ghosts suggests you can “read” a city through its old cinemas and come to understand something about its civic and cultural life – not high culture but mass culture. Even the movie marquees on those places marked time, in their own way. A vintage photo that touts whatever film was playing, ties the image to a particular era as definitely as a yellowed newspaper. In his film, Filho makes the wry observation that marquees for the venerable Recife cinemas – the ones located within view of each other, anyway — seemed to be in conversation.

“I think I have the right to miss the marquees in the city landscape,” he says. “I think there was something about the marquees that gave the city something special. It really felt like they were talking to each other.”

Gone from Recife – and so many other places around the world – are those marquees and the cinemas they adorned. What have we lost, the documentary implicitly asks, when a trip to the movies now amounts to visiting an utterly nondescript location?

“Of course, we all go to multiplexes, and they’re mostly black boxes with seats,” Filho comments. “You never remember if you saw a film on screen 3, screen 14, or 11. It’s meant to have no personality, which is a very strange business model, but it seems to work for them.”

‘Pictures of Ghosts’

Courtesy of Wilson Carneiro de Cunha

The decline of the movie palace has run in parallel to the decline of so many urban centers – not only in Brazil but around the world. Nostalgia for an earlier time of urban vitality permeates Pictures of Ghosts, but it’s a nostalgia of inquiry and reflection, not stale sentimentality.

“I did think about that when I was making the film, and I was always questioning myself about the quality of the writing and asking my friends, does this sound gooey? Does this sound honest? I was also very skeptical of giving the idea that I believed everything was much better in the past, which is dangerous, I think,” he says.

His goal, then, is not to rewind the clock and keep it there, but to think about the past and all that has changed.

“I’m presenting, I think, ideas about time and place and memory,” Filho says. “And I’m happy with that.”