Before Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon debuted at Cannes, audiences had a preview of what his leading lady Lily Gladstone could do in the Sundance title Fancy Dance, in which she played a Native American aunt who would do anything to keep her family together. Family plays a big part in Scorsese’s adaptation of David Grann’s 2017 bestseller too; in his telling of the horrific true crimes committed against the oil-rich Osage people of Oklahoma. Gladstone’s real-life character, Mollie, marries Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) and stumbles on a plot devised by her husband’s duplicitous uncle William King Hale (Robert De Niro) to kill her kinfolk for their money. Here, Gladstone discusses what it meant to tell Mollie’s story.

DEADLINE: Congratulations on your Golden Globe nomination.

LILY GLADSTONE: Thank you. I’m amazed. But I’ve been chronically amazed for the last two and a half years.

DEADLINE: Before we talk about Killers of the Flower Moon, I just want to say how much I loved Fancy Dance and I love that you get the chance to talk about it more in tandem with the success of this film.

GLADSTONE: Seriously, yeah, me too. I knew when we talked about it at Sundance that it was going to have some parallel, and I was hoping that Killers would help uplift it a bit, but then having it be out and seeing just how complementary they are. Same place, in a lot of ways, same story, just a hundred years later.

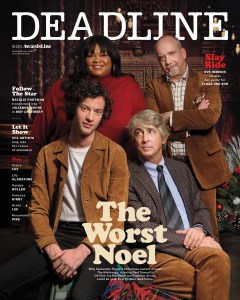

From left: Leonardo DiCaprio, Lily Gladstone and Robert De Niro in Killers of the Flower Moon.

Paramount Pictures

DEADLINE: Right after the actor’s strike, you released a message on social media about Killers of the Flower Moon, saying, ‘If you’re going to watch this, be ready.’ You’d had some time to process while the actors’ strike was going on. Tell me about the decision to post that online.

GLADSTONE: In conversation with, particularly Native women, since the film had come out, that kept coming up. The idea of seeing it in community together and having a way of unpacking it was crucial. And not just Native women. A lot of Osage people that I’ve talked to since, who saw it together for the first time talked about how important it was that they did see it together, and then what a different experience it was to walk into a theater alone later, with a broader audience, and really how triggering that could be. People sniggering about the length of the film, people laughing at inappropriate moments, hearing Taylor Swift [her Eras Tour film] blasting from just one theater over.

Indian country was booking out entire theaters and dressing up to the nines, wearing traditional regalia and modern beautiful clothes they were waiting to bust out. There were little premieres all around, and I kept getting photos and texts from people that were so excited about it, and I just kept having this feeling of, ‘I hope the excitement’s not overwhelming what the story’s actually about.’ Marty [Scorsese] pushes back against it all the time, calling film and cinema ‘content’. But modern audiences are so used to going in and seeing content that sometimes you forget what the story’s about. And I know Native people, Native audiences, weren’t forgetting that element walking in.

A lot of it was things that I’d been wanting to say the whole time, and honestly in a lot of ways, kind of regretted that I didn’t find a way of doing so earlier, or just wished that I could have, because what I was saying in private messages to friends was what I wanted to say to everybody — it was a very triggering experience for a lot of the audience who went. And I think a lot of that had to do with who you saw it with, and how you were able to unpack it later because this was a really traumatic time. And a lot of the Osage that consulted on the film have seen the film and are proud of the film. It’s their incredibly triggering history told in a way that people care about it and are shocked by it as they should be.

DEADLINE: It’s opening old, deeply painful wounds for people.

GLADSTONE: Yeah, even though it’s opening old wounds and bringing up traumas, that’s a big step in the process of healing. And I think ultimately, art helps us do that, helps us process these horrendous histories in a way that is more living, is more animate and is more lasting in some ways, because of the emotional investment you have in it. But that healing process is painful. I think healing has been so commodified in modern society that we think it’s supposed to feel good. It’s like we’re sold a healing practice as something that feels good all the time. And that’s not the nature of it. A lot of it is opening wounds and allowing things to breathe, which stings, it bleeds, it hurts, but it’s essential to let it out, to really do some restorative justice about this history.

DEADLINE: I met with Osage consultants on the film, Chad Renfro, Addie Roanhorse and Julie O’Keefe. It was a really moving conversation. Tell me about the ways they helped you find Mollie and the accuracy of representing her.

GLADSTONE: Yeah, that was everything. All of my instincts about who Mollie was and how to approach her, they were instincts that I wanted to vet and check with our consultants always. And a lot of the times, the bedrock that I drew from, within my own community and own family, was a really good starting point, but it was so invaluable, every single day, knowing that there was an Osage person somewhere within earshot, that if I needed to check something in the moment, they were there and that they were really part of the storytelling and really part of the character shaping.

For the early preliminary work, I knew I was going to find Mollie in the language first, and I did end up finding that when I was performing her in Osage is where I found her voice, I found her movement, I found her. I was often more comfortable performing Mollie in Osage than I was in English.

From left: Gladstone, Robert De Niro and DiCaprio.

Melinda Sue Gordon/Paramount Pictures/Everett Collection

DEADLINE: How tough was learning Osage and how long did it take?

GLADSTONE: The day that I got cast, I downloaded the language app and taught myself as best as I could the orthography, the alphabet system. About two months after that, I had a pretty good handle on what I thought it was supposed to be, but that’s when I got into language lessons with [Osage language teacher] Christopher Côté, and we met three times a week, an hour per session, for about two months before I ever even got to Oklahoma. And it was clunky, it was messy. My greatest fear was that I was going to apply a Blackfeet dialect, which is the Indigenous language I don’t speak fluently, but I’m able to introduce myself in. I can count to 10. I can say the bad words and animals and stuff like that. But Blackfeet has a completely different syntax, different syllabics, different phonemes, all of it.

Osage was hard. Osage has a lot of overlap with Lakota language. They both share a similar, or the same language base, but Osage also has a lot of influence from centuries of trade with French, with Spanish. So it’s an incredibly unique and very difficult language, and was spoken at a pace that just every time I thought I was going slow enough, I needed to still slow it down.

When I got to set, I continued the language lessons, and started working with [Osage language consultant] Janis Carpenter to refine the women’s dialect, because men and women have, and had, especially at the time, two different dialects of the language. So I say that Chris helped me lay the foundation and put up the framework of the house and Janis is the one who helped me pick the wallpaper and dress the windows and get it really refined and lived-in.

I do find that the heightened emotional scenes are the ones that I still have language for. They’re the ones that I still remember. If you were to ask me to speak Osage right now, I would go straight to the argument that Mollie and Ernest are having, the one that’s not subtitled, because that was performed in such a heightened emotional state, but it was available to me only in Osage. We’d never once rehearsed that scene in English. It got in me and it stayed in me.

DEADLINE: What was the casting process like for you?

GLADSTONE: The first time that I met Marty was over Zoom. I keep wanting to say Skype because I’m a millennial.

I got the request to speak with Marty. I remember being really, really grateful that I was allowed to have this life-changing audition moment in my own bedroom. I would’ve been a mess if I’d been in person with him and had a whole plane ride, had a whole weekend. I didn’t have to go outside of my own element. And I think that was so crucial with Mollie and went into a lot of our understanding of her long-term, like, why didn’t she leave? It’s like, that’s her land. That’s where she’s from. She was grounded in place, and I think it was actually really fortunate that I was able to take my first meeting with him from home, where I could hear my parents, and overhear them in the other room.

DEADLINE: What was your impression in that first meeting?

GLADSTONE: Honestly, Marty is so efficient when it comes to these things that my first meeting with him really was about the text. It was performing the sides I’d been sent with Ellen Lewis, his casting director, and talking a little bit about how the sides had changed. I didn’t want to be too effusive about it at the time, but it was such a relief when I got the new ones. I’d auditioned with different sides a year earlier, and it definitely felt to me… there were monologues that were highly expositional. It just felt like this is a tertiary character when I read those, and it wasn’t the Mollie that I knew I would be able to perform. But when I got the new sides, suddenly, there were spaces, there were reactions, there’s time to let things marinate. There’s beats written into it. It clicked.

It felt like such a divine moment, and it gave me so much faith. It was scary, the idea of booking this role, of doing this story in a lot of ways, it felt way too big. But luckily, there were all of these little green lights that you get, and sometimes in very cosmic ways. When I was ultimately offered the role, we did the reading with Marty, it was great. It was hard to tell because you get used to people having respect for actors, putting in the work in an audition and being kind no matter what. So, it was hard to tell if the praise was kindness or genuine. But I got a call immediately after, wanting to schedule a meeting with him and Leo.

I think about how excited he got when I compared this new treatment to The Quiet American by Graham Greene, that the history will hit harder if there’s an analogy in a relationship story. And I recognize it now, when something resonates with [Scorsese] it’s a little like a jolt of electricity passes through him, and he just gets excited. He usually turns to whoever’s closest to him and taps them a lot of times. Like, are you hearing this? He has that energy constantly, and it’s like even though he and Leo weren’t in the same room, they were two faces on the screen, it almost felt like he was tapping Leo’s screen.

When the call came in, I was expecting it was going to be to schedule a true chemistry read with Leo and I, but it was the offer. The day I got the news was actually Mollie Burkhart’s birthday, December 1st.

Gladstone with director Martin Scorsese on set.

Melinda Sue Gordon/Apple TV+

DEADLINE: Tell me about your connection with Mollie’s family. And how did they respond to your work on the film?

GLADSTONE: The person whose opinion I valued most at the end of the day was always going to be Margie Burkhart, who was Mollie’s granddaughter and Cowboy’s daughter. Margie had never met her grandmother — Mollie passed away in 1936 — but she had pieced together her sense of who Mollie would’ve been from little stories from her dad, but not many. I think this entire period of time was very much not spoken of for many generations. People wanted to move on. [William] Hale was cut out of pictures and people stopped saying his name. So, when we were meeting with Margie, I knew that she wasn’t going to hand me a list of, ‘This is Mollie and how to play her.’ There was no blueprint, but where you find that is the legacy they leave within their family. So, there’s a lot of small gestures that came from that meeting. The way Margie just is around people. A lot of that went into Mollie.

But one thing that stood out to both Leo and I was how much of a puzzle it was, and how much Margie knew it was going to be a task for Leo and I, to really find what that marriage was. Because it’s so impossible to believe that there was real love there, even though Ernest insisted it until his dying day, and even though the community has said there was love there, Margie has said there was, but then she was incredibly skeptical in our meeting about how we could accomplish it. So we talked about it every which way. And ultimately, I feel like I almost had her looking over my shoulder the whole time and was so nervous and was just convinced for a really long time that she would see it and just be appalled.

Read the digital edition of Deadline’s Oscar Preview issue here.

DEADLINE: So, what happened when she finally saw the film? What did she say to you?

GLADSTONE: I got to see her in person at our Osage premiere. And she talked about how she was amazed that we had done it, we accomplished it. And she just remarked on how incredible it was to see how their dynamic may have been. It felt like she said, “This must have been what their marriage was like,” in this way that’s been so mysterious to her. She just embraced me so tightly. She introduced me to her grandchildren, so Mollie’s great-great-grandchildren. I remember the youngest one that I met. I could see Mollie’s face just so perfectly, and for a second the way it felt like I was able to look at her, it was like she was meeting her grandma. It’s like the way she met her grandma was through this film.

And Leo has said it before, he’s talked about he felt like I was channeling her. I didn’t really necessarily see it that way while I was performing. I was there to do a job. But I must have disappeared in her a little bit because when I watched the film later, I felt Mollie so intensely. I felt protective of her. I felt the way that the rest of the audience meeting her for the first time must’ve been feeling.