Everyone wants to talk about the Chevy Tahoe.

In the first big trailer for Halo, Paramount Plus’ big-budget adaptation of the decades-spanning Xbox sci-fi shooter, a rust-colored SUV appears tucked inside a mining compound. The vehicular prop got just enough airtime during the Super Bowl spot that people recognized the model as a GMT800 Tahoe, produced by General Motors from 2001 to 2006 — more than 500 years before Halo’s hero, Master Chief, was even born.

The Tahoe wasn’t what Halo’s creative team expected people to notice in a two-minute trailer full of Warthogs, Phantom dropships, a couple Mongooses, and a number of other fancy space vehicles. But people noticed, and those few shots of the Tahoe went viral.

“It’s both frightening and exhilarating to know people care that much,” Halo showrunner Steven Kane tells Polygon.

The Tahoe is there for a reason, Kane says. 343 Industries, the development studio behind the Halo games, spent nearly a decade turning Halo into a tentpole TV series. When it finally became a reality, 343 worked with the Paramount Plus production team to scrutinize every choice, big or small. Each prop was carefully thought through and set with intention. Something like a car couldn’t make it on set by accident.

“For people who haven’t spent time in the game industry, there’s no such thing as too fast a shot to notice something,” says Kiki Wolfkill, a studio head at 343 and Halo’s executive producer. “We have to assume every single frame will be examined.”

Kane and the Halo team knew the series would come alive in the tiny details, and they debated everything, from the plates space humans use to the economics of Halo world manufacturers. But making Halo work as a television show is about matching the micro with the macro: Even with the show premiering on March 24, very little is known about what the Halo show actually is. 343 Industries and Paramount Plus have been careful not to share too much, but in a series of new interviews with the creators, one point is emphasized over and over: Halo the show is not Halo the game. Not exactly.

“What people see will be different from what they’ve expected,” executive producer and director Otto Bathurst tells Polygon. “And hopefully a strong percentage [of fans] will be pleased with it. But listen, I’m sure it’s going to ruffle some feathers.”

Combat, evolved

Image: Paramount Plus

Steven Spielberg called his shot at E3 2013: In a pre-recorded video, the Oscar-winner announced his and Microsoft’s intention to adapt Halo into a TV series. The plans were scarce; the show would be an Xbox Live exclusive, and Microsoft was going to spend a lot of money on it — on the level of Game of Thrones, suggested one report from the time. The show remained under wraps for years, then resurfaced in 2019 when Microsoft announced that Awake creator Kyle Killen would mount Halo at Showtime, with Spielberg still on board as an executive producer. Following a dramatic shift in the business of television toward streaming and plenty of years of development hell behind it, Halo has changed once again. Halo is now a Paramount Plus exclusive, with Kane, whose previous credits include The Last Ship and The Closer, co-showrunning and Bathurst (Black Mirror, Robin Hood) directing the first two episodes of the nine-episode season.

Since the beginning, 343 Industries and Spielberg’s Amblin Television have described the series as taking place during the 26th-century interstellar war between humans and a hyper-religious alien group called the Covenant. Everyone involved with the series resists calling Halo an exact adaptation, but it carries on the legacy of the 2001’s Halo: Combat Evolved, developed by Bungie and published by Microsoft — the company that owns the franchise today. As Master Chief, Halo: Combat Evolved players do a lot of shooting aliens. But behind all the weapons and military jargon, there’s a story there, one of a very powerful soldier, stacked with a sassy AI computer program called Cortana, tasked with saving humanity from aliens that desperately hate humans. The war is fought over the Halo, a ringworld believed to be a life-ending weapon or part of a world-changing prophecy, depending on who you ask.

The idea of the Halo show was always to focus on Master Chief, now played by Orange is the New Black’s Pablo Schreiber. That was always the key for Wolfkill, who’s been attached to the project from the early days in her role as Halo’s transmedia executive.

“When I think about what the series is, it’s a story of the Master Chief understanding who he is as John,” Wolfkill says. “It is introducing a lot of Halo elements, introducing the world of Halo, with its places, its look, feel, and the value system that sits underneath it that pervades all of our things we do in the Halo universe, which is a story about heroism and hope and humanity, and the idea of humanity being something worth saving.”

Image: Paramount Plus

The TV series’ story won’t be identical to the story established in the seven core games and swath of canon spinoffs; instead, Halo will exist like an alternate universe, in a story referred to by 343 Industries as the “Silver timeline.” In a lengthy post published in January, the company explained some of the story divergences delved into in the trailer: For one, Master Chief is no longer the only Spartan alive at the time of the events of the first game, 2001’s Halo: Combat Evolved. In Combat Evolved, Master Chief was heralded as the last Spartan. In the TV show, he’s got a new crew, dubbed the Silver Team; the lineup includes Vannak (Bentley Kalu), Riz (Natasha Culzac), and Kai (Kate Kennedy). Plus, there’s a human woman involved with the Covenant: Bathurst says Makee, played by Charlie Murphy (Peaky Blinders), is a sacred Reclaimer of enormous value to the Covenant, who captured her when she was eight and raised her as their own.

Kane says that the Halo show’s timeline was built to protect the franchise’s original canon, while still using it to build out new stories in unexplored “nooks and crannies” of the galaxy, and ground an interstellar war in an ensemble of characters. Master Chief is a huge part of that; in Halo’s core games, players are Master Chief — locked into and controlling his body to enact the ultimate power fantasy, being the world’s hero. He’s never been a man of many words, but this new format will change that.

“You really don’t know who this person is. We took that as an opportunity to have the character himself figure out who he is, while we learn who he is at the same time,” Kane says.

Image: Paramount Plus

Beyond Master Chief, the expansion of the Spartan program allows the show to grapple with bigger questions. Master Chief’s fellow Silver Team Spartans have that same complex backstory: As kids, they were trained and augmented to be controllable human weapons. Halo is ultimately a drama of the consequences of this realization, smashing together the lives of Vannak, Kai, and Riz and their creator, Dr. Catherine Halsey, played by Natascha McElhone (Californication).

“There’s so much to explore in terms of the rights and wrongs when humanity is at stake,” Wolfkill says. “How far are you willing to go to save it? And what does that mean? The Spartans are very much emblematic of that. John, in particular, watching him understand his origins lets us as an audience reflect on the decisions that were made for him — to reflect on that very basic human state, which is, when there is an existential crisis, what are the ethics?”

The world-building blocks

343 Industries senior franchise writer Kenneth Peters, essentially the Halo team’s lore expert, tells Polygon that the show’s overarching plot and Master Chief’s deeper backstory fall in line with what fans have learned over the years. “We do touch on origin stories. Either they’re directly taken from what’s been established before, or it just fleshes out what’s been shown before. We tried not to change things like origin stories,” he says.

Whereas the games centered around Master Chief “shooting aliens in the face,” as Peters puts it, the TV show isn’t only focused on military operations: The civilians of these colonies and their struggles — against the Covenant and the United Nations Space Command — are interwoven with the Spartans. Wolfkill describes the end product as similar in structure to HBO’s Game of Thrones, where the story spans “sprawling locations” as multiple storylines “cross and diverge” throughout the nine episodes.

One of Halo’s branching storylines follows the insurrectionists of Madrigal, the dry, dusty outer colony planet that’s also harboring a 500-year-old car. This is where Kwan Ah, a daughter of an insurrectionist played by Yerin Ha (Reef Break), enters the picture, and allows Kane to pull from stories that originate in Halo lore but haven’t been explored in the games. In the established Halo saga, insurrectionists have been fighting the United Earth Government and the United Nations Space Command for quite some time, starting before the Spartans were created and completed. Earth and other planets close to it are favored by the government, and humans in the Outer Colonies, like Madrigal, often feel oppressed by what they feel is imperialist rule.

Halo production designer Sophie Becher describes Madrigal as a world with few reasons, aside from the highly coveted deuterium, which is primarily used for military equipment. Everything on the planet is stuff that the UNSC flew up there when it was first colonized, and the people dropped there essentially had to fend for themselves. “They had to build their environments out of what was there, which is the soils,” Becher says. “On this particular planet, everything is adobe-built apart from the components that would have been flown in up the shop. You have an amalgamation of stuff they’ve created on that planet and other things that have come from the UNSC itself.” Like a Chevy Tahoe.

Image: Paramount Plus

In the show’s timeline, humans on Madrigal and other Outer Colony planets like it, banded together to rebel against the Earth government — essentially starting an interstellar war. And that leads to the Spartan-II program. “Their backstory is pretty dark,” Kane says. “They were designed to quell a human rebellion, and they were killing humans before the aliens even showed up. It’s definitely a testament to Halo that we’re able to tell a complicated, morally ambiguous story like that.”

Bathurst tells Polygon that Kwan Ah and Master Chief’s relationship, a core component in season 1, is driven by the insurrectionist story. Long ago, before the Covenant arrived, Master Chief was responsible for killing her mother — wiping out insurrectionists was his mission, after all. Madrigal, and Master Chief defending Madrigal, will play out in Halo’s first episode, when the Covenant attacks in search of an Halo ancient artifact.

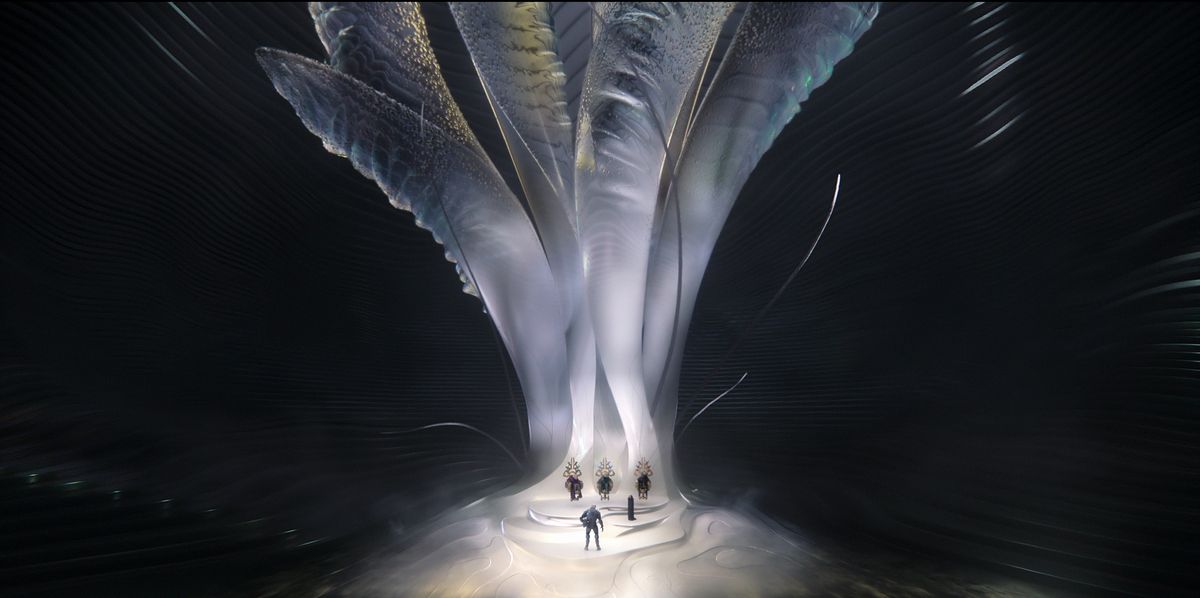

Digging deeper into the human element, Halo demanded a need for new visual and world-building innovation beyond the recognizable iconography of the game series. “What does a house look like in the Outer Colonies?” Peters remembers asking. “What does urban life look like in Halo?” “We have, for example, New Alexandria from Halo Reach, but that’s a very limited slice needed for the games,” he says. “We had to invent and extrapolate a lot of material for civilian life in the Halo universe to flesh out the stories we’re telling.”

Becher worked with Kane and director Bathurst to build out sets with lived-in design and as many practical environments as possible — the right environment only helps the actors fighting an alien war in combat suits behave in a more believable way. “I felt that if there was mud, you had to have mud,” Becher says. “And if it was very dry in an area, we would make it as dusty as possible.” Of course, that doesn’t mean there wasn’t VFX involved; the show is set on multiple futuristic planets were alien spaceship landings are the norm.

Journeying beyond the known Halo universe meant Becher wasn’t beholden to cemented canon. She and her team started by thinking about the planet’s microclimates and how a human would survive. “I was very keen to make each planet feel very individual in its environment,” Becher said. “I started literally not from referencing anything in the game, but actually how people would live on these individual planets.” The production designer said fans should expect to see quite a few different locations, but pointed out a few of her favorites that Halo fans would recognize: Arizona, an agricultural planet built around hydroponics; the Rubble, a renegade community set up inside an asteroid; Fleetcom, the militarized base; and, of course, Madrigal.

Image: Paramount Plus

The direction of season 1 also demanded that Kane and his team expand the Sangheili language that the Covenant aliens speak. The Covenant themselves are a group of aliens, not a singular race. They’re bonded as religious zealots, worshiping a mysterious group of god-like figures called Forerunners and the Prophets. The common language they all speak is something that factors into the game, and for which 343 Industries has developed some rules for, but the show made it something that can be picked up. “We actually built it out as a total language that could be taught on Duolingo,” Kane says. Specifically, David J. Peterson, who invented the Dothraki language structure for Game of Thrones, created the rules and taught humans how to speak it — a challenge that was hard, given that it was built out to make sense from an alien’s mouth.

“He did it for the mouth, the throat, and the vocal cords of an alien,” Kane says. “It’s very guttural with lots of tones and clicking and clacking, because the mandible of a Sangheili has like four or five tentacles, like [how] a starfish opens up.”

Halo is a Halo is a Halo is a Halo

Though things have evolved past the games, the two decades of design work from the Halo games’ art teams hasn’t gone to waste. “Every fusion coil, every ammo crate … there’s actually shipping labels and manufacturers all over that stuff,” Peters says. “And I would say 99% of the time I don’t even think super-Halo fans would even really notice a lot of that. But when you’re on set, and you’re just walking around, there’s ammo crates and they have Misriah Armory on them. Then you look really closely and see it’s carrying 200 7.62 mm rounds in this case […] We gave [the production team] the reference material and they studied it. They probably know Halo manufacturers and companies better than I do.”

Peters pointed to this as a place where even the show had an influence on the most recent game release, Halo Infinite: “We actually backported a lot of that into the game,” he says, noting that the sidekick pistol in Halo Infinite sports the logo of Emerson Tactical Systems, a made-up company originally created for the show.

Image: Paramount Plus

There’s potential for the show’s timeline — even though it’s not the “core” canon — to continue to influence the future of Halo games, too. The new Spartans, Vannak, Riz, and Kai, aren’t necessarily going to be in Halo Infinite 2, Peters says, but they’re characters that exist in that canon.

“They might have died on Reach in our core canon, but they might not have,” Peters says. “We try not to change things where we didn’t need to change things. We try not to add things to either the game or the show that weren’t useful.”

Cortana, once again played by Jen Taylor, falls into that category. For her to make sense to TV viewers, Bathurst says the team focused on Cortana’s creation — she’s essentially an AI clone of Dr. Halsey — and Halsey’s agenda in creating her. The character herself has become an important figure in Halo’s story, even taking center stage in Halo Infinite. But she started, you can say, as a UI conduit for the player in Halo: Combat Evolved, someone to guide you around the game. A television show doesn’t need that.

“If a character like Cortana hasn’t been contextualized, if she hasn’t been given a strong reason, she might appear sort of gimmicky, sci-fi, and a bit gamey and silly,” Bathurst says.

Structurally, Bathurst says Halo veers away from the combat-driven action of the video games, because it has to — especially if it’s going to appeal to people who are simply fans of sci-fi or drama. Action and large-scale battles will happen across the series, of course: Bathurst says to expect three massive battles, with other smaller skirmishes tucked into the nine-episode series. When asked who the Halo show is for, everyone had a similar answer. The team wants Halo franchise fans to love it, but for it also to be welcoming to new viewers — the idea is that rich stories and big sets allow for both kinds of viewers to find something in Halo.

“It’s been a long time in the waiting,” Bathurst says. “There’s a lot of pressure on it. A lot of people have a lot of very high expectations. It’s going to be a tough crowd, that’s for sure.”