Remember that one friend of yours when you were nine, who said that they’d end up playing professional basketball? We have some bad news for you. We checked in with them, and it turns out they’re instead in prison, for a $30 million Ponzi scheme that targeted wheat farmers. No one predicted that would happen — especially not the wheat farmers.

Some people’s futures, however, really are predicted long in advance. Occasionally, this means fate knew about their eventual triumph. Other times, it means they were always doomed to suffer tragedy.

‘I Don’t Want to Play 10 Years in the NBA and Die of a Heart Attack at Age 40’

Four years into his career in the NBA, Pete Maravich told the Beaver County Times, “I don’t want to play 10 years in the NBA and die of a heart attack at age 40.” His point was that he could leave and do something else with his life anytime he wanted, and perhaps he was going to soon.

Don’t Miss

Six years later, he was still with the NBA. He now joined the Boston Celtics the same season they first got Larry Bird. But a major knee injury he’d suffered a couple years earlier still held him back, so he now retired. He’d played exactly 10 years in the NBA.

via Yahoo

Seven years after that, he found himself playing basketball again, not professionally but just at a pickup game at his local church. During the game, his heart gave out, and he fell down dead. He was 40 years old.

That was the end of Pete Maravich, a man who was, according to John Havlicek of the Boston Celtics, “the best ball-handler of all time.” And truly, there is no greater compliment you can bestow on someone than to say they were great at handling balls.

‘There’ll Be a Man on the Moon Before He Hits a Home Run’

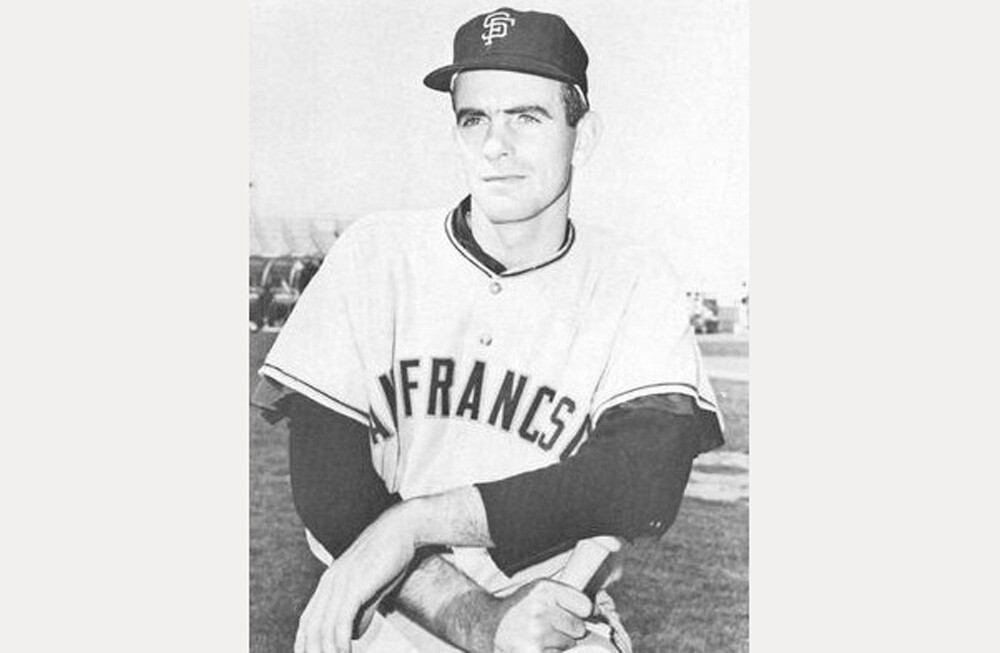

Not all professional players get that sort of praise. Consider Gaylord Perry, a man whose name we refuse to mock, and we just made a joke about handling balls. Perry would go down in history as a terrific pitcher, but he wasn’t a good hitter. He had a career batting average of .131.

“There’ll be a man on the moon before he hits a home run,” said Alvin Dark, Perry’s manager during his time with the San Francisco Giants.

That might have been a sick burn in 1962. But on July 20, 1969, two men did land on the moon. Within one hour of the lander touching down (though another six hours or so before Neil Armstrong got out and walked), Perry hit a home run. He’d go on to hit another five of them over the next 14 years, just to prove that this wasn’t purely a matter of the stars aligning.

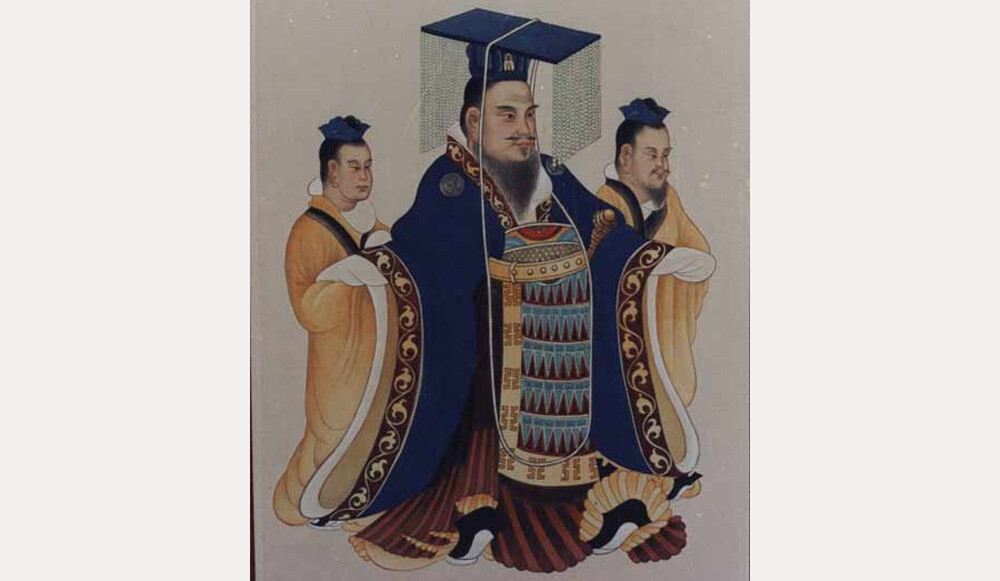

‘An Aura of Emperor Emanates From Chang’an Prison’

If you’re a king and keep a soothsayer around, they’ll offer you a hundred nonsensical prophecies that never come to pass. But you’ll listen to their advice anyway, because if you were the sort of person to be rational about this sort of thing, you’d never have hired a soothsayer in the first place.

So, during the Han dynasty, when a soothsayer told China’s Emperor Wu that “an aura of emperor emanates from Chang’an prison,” Wu feared that someone in that prison would overthrow him. He ordered the inmates slaughtered.

via Wiki Commons

“Woo hoo!”

“The inmates of Chang’an prison, that’s who.”

If this were a legend, the assassins would have missed one single prisoner, who’d grow up and slay Wu in revenge for the attack. That exact thing didn’t happen, but what did happen was pretty damn close.

Wu lived to the age of 69, and he named his six-year-old son as his successor. He’d also had an older son, Ju, who’d tried a rebellion and ended up killing himself, leading most of his own family to be executed. Wu’s young son became Emperor Zhao, and he died at the age of 20 without leaving an heir. The court appointed a new emperor who lasted just one month before they forced him out and found someone better.

This new emperor was Ju’s grandson. Ju’s family, it turned out, had not all been executed. This grandkid had grown up, thanks in part to having been cared for as a child — by the warden of Chang’an prison.

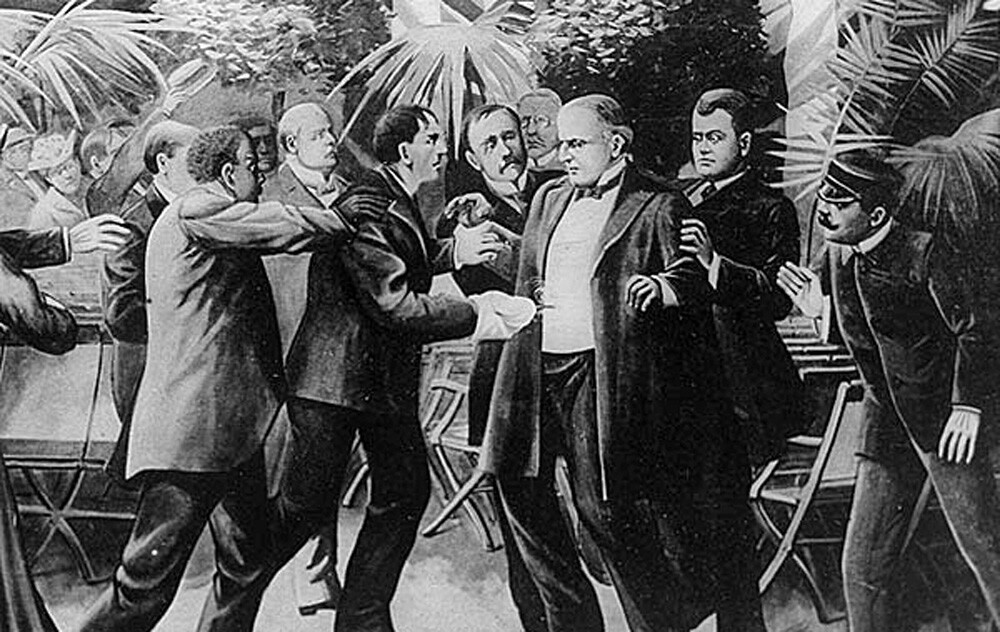

‘Don’t You See That I Can’t Leave This Case, Even If It Were for the President of the United States?’

Dr. Roswell Park, a skilled surgeon, was prepping an operation on September 6, 1901. He was getting ready to remove a lymphoma from a patient when his staff summoned him to the telephone. No matter how urgent the call was, he had something important to do, so he told the caller, “Don’t you see that I can’t leave this case, even if it were for the president of the United States?”

“Doctor,” said the caller. “It is for the president of the United States.” President William McKinley had been shot, and they wanted Park patching him up.

That’s not a joke. That actually happened.

If you’ve heard this piece of trivia before, you might have imagined this doctor now felt embarrassed for saying such a thing and rushed to the president’s side. But Park meant what he’d said. He ended the call and finished the lymphotomy. Only afterward did he take the train to Buffalo to attend to the president, who was being inexpertly treated by a gynecologist. A doctor’s responsibility is to their patient, not to whichever next patient might be more important.

‘Math Says You Will Die at 64’

McKinley died, possibly because Park wasn’t there early enough. But a president’s death isn’t the end of the world. The vice president will step in and take over the role, and McKinley was succeeded by Theodore Roosevelt.

When Lyndon B. Johnson was in office, however, he decided his death could not be an option. The nation had just suffered through one president dying and being replaced, and he figured it could not handle another. So, as he was nearing the end of his first full term, he wondered if he’d survive a second, and he decided that if he likely wouldn’t, he would not run for reelection.

He launched a “secret actuarial study” to determine his personal life expectancy, based on how long people in his family had lived. The study estimated that he’d die at 64. Because of this, and despite already having won the New Hampshire primary, he announced that he was not seeking a second term. Richard Nixon won the 1968 election instead.

Johnson would go on to die at 64, as predicted. A heart attack killed him two days after Nixon’s second inauguration. That meant he actually could have lived out a full second term of his own — if he died on that exact day regardless, but given the stress of the presidency, his heart attack might well have come a bit sooner had he stayed in office. Either way, it sounds like he relinquished the presidency for the sake of the country, and thanks to his sacrifice, no Democratic president ever died again.

No, really. In the fifty-plus years since Johnson’s death, no president (or ex-president) from the Democratic Party has died. Now we have to hurry up and publish this before Jimmy Carter tries to prove us wrong.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.