If there were one thing that might deter you from taking up your old man’s profession, it would surely be him being arrested, imprisoned, harassed and alienated for more than a decade for practising it.

And then imprisoned again. Reiterating the madness into which Panah Panahi has chosen to enter, his father, the renowned Iranian film director Jafar Panahi, was this week sentenced to serve a stayed six-year prison sentence after inquiring about the detention of two fellow directors.

Speaking to me a few weeks before this episode of staggering injustice, Panah admits that sometimes he has questioned his father’s idealism. “You wonder: who are you doing this for?” he says. “What’s the point of this kind of resistance? From our family’s perspective, you sometimes think that, well, maybe it wasn’t worth it.”

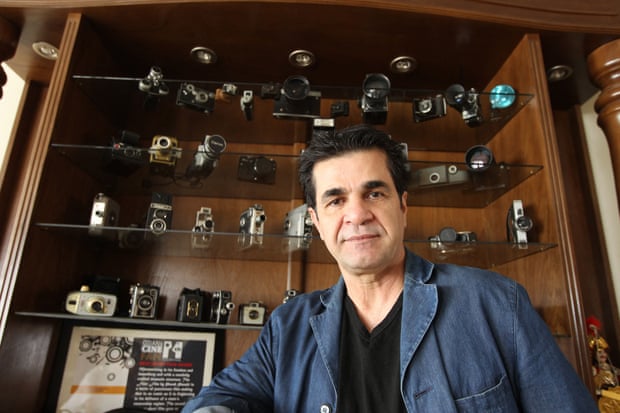

He is staring down a video connection with heavy-lidded, intense brown eyes from his apartment in Tehran, speaking to me through a interpreter. Only his father, of course, can answer such questions. Even before the latest events, Jafar – originally sentenced in 2010 for what the regime deemed anti-Iranian propaganda – had paid the price of opposition: banned from film-making for 20 years; banned from foreign travel. He was free to move inside Iran, but was socially ostracised, with even some of his closest friends “afraid to utter his name”, according to his son.

Now Panah has chosen to step into this minefield with his debut feature, Hit the Road, a pained and funny road movie about Farid (played by Amin Simiar), a young man travelling with his family to the border to escape the oppression of Iran. After making a few shorts, Panah, 38, procrastinated about making a full-length film. “I was going through a very deep depression,” he says. “I realised that I was paralysed. Everybody expected me to excel in everything I did and judged my results according to my father’s standards. I wanted to become Panah Panahi and free myself from ‘the name of the father’. But it always felt like this was only possible by doing something perfect and flawless … I became a perfectionist without even understanding why.” His girlfriend eventually nudged him out of this rut, encouraging him to “become independent without having to deny my father’s valuable heritage.”

Hit the Road was indirectly inspired by the departure from the country of his sister, Solmaz (although she took a flight and was not smuggled out over land, as in the film). When Jafar was interrogated by the authorities, her name kept cropping up, so her father suggested she should leave. The night before her departure marked her brother so indelibly that he based his film on it. “It was the feeling, the mood, of that last evening, when friends and family came,” he says. “This denial. Not wanting to show how you feel, not wanting to acknowledge what is going on, just pretending that everything’s fine.”

This self-effacement is related to a form of politesse and etiquette known in Farsi as taarof. Hit the Road captures this strikingly in the torrent of make-believe and banter the family uses to disguise the purpose of the journey from the hyperactive kid brother (an ultra-cute Tasmanian devil of a performance from Rayan Sarlak). The film’s first image is of him playing an imaginary piano on the felt-tip keyboard on his dad’s plaster cast – but what Panah cuts to is the mournful Schubert that is the adults’ inner soundtrack. “That’s our DNA, that’s Iranian culture,” he says. “You always have to navigate between what can be said and how to say it.”

Negotiating this has been even more fraught since the Iranian revolution in 1979 ushered in the repressive regime. “When you’re in a society in which you’re always trying to allude and avoiding cutting to the chase, how can you have healthy relationships and a healthy society?” says Panah, lighting another one of the many cigarettes with which he punctuates our interview. “For me, it’s nothing but a source of anger.” He glowers into the webcam.

Such issues of self-expression are all the more acute for artists. But according to Panah, absurdity reigns in Iranian cinema. In order to get the shooting permits he needed, he wrote a dummy script that was palatable to the authorities. Even then, they felt it needed a positive final moral, like encouraging employment. “So I said: OK, they are travelling because they have a piece of land at the border, and the older son falls in love there with the daughter of a local guy, and they get married and create jobs on their land. And that’s how we got their approval; it’s as silly as that.” You begin to understand the need for the kind of cinematic taarof that saw Abbas Kiarostami couch his early social commentary in children’s films, and the use of parable and allegory as means of casting askew glances at Iranian society in the likes of his father’s Cannes winner The White Balloon.

But, given his surname, isn’t Panah going to get it in the neck when the government watches the finished film? He is indignant. Everyone submits these dummy scripts, he says, and there are no consistent directives to follow, just the whims of the official handling your case. “You cannot imagine how crazy the whole system is. We’re confronted with this heterogeneous, unpredictable, completely illogical system. The only way to survive it is to be just as hypocritical as they are.”

One man who seems to have managed to stay resolutely unhypocritical is his father. Despite his film-making ban, Jafar has managed to make four features, including 2011’s This Is Not a Film and 2015’s Taxi. There has been much speculation that the recent arrests herald a further crackdown on freedom of expression in Iran and, since the recent events, Panah is cautious and won’t say anything further about Jafar; his mother, Tahereh Saeedi, has called his imprisonment “a kidnapping”.

In our conversation, though, Panah is rueful: “Maybe he should have been more clever, less radical in how he expressed his resistance or his opposition.” Is he angry at his dad? “It’s not as one-dimensional as that. It depends. Sometimes I can be irritated, sometimes I can be supportive. But when I look at his journey, when I see the struggle that he has chosen to carry on, which is one trying to take his society to a better space, this is a journey I respect – and I would respect it for anyone.”

Despite an Iranian cinema landscape he paints as “pretty negative”, Panah sees hope in the collective ethos in his country. “Because we’re always trying to find other ways of reaching our goals, I think Iranian directors are among the most inventive in the world.” He has a clutch of fingers on his chin again, as if he is trying to pull the thoughts down out of his head. “That permanent confrontation with obstacles makes them more inventive and more questioning of themselves, their habits and the world around them.”

But there is an energy about Hit the Road – different from the often self-conscious, intellectualised works of his father’s generation – that suggests a new dawn. Near the end of Panah’s film, he includes a long shot flying over an infinity of cracked desert flatland. It seems to be a homage to the space-gate sequence in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, referenced here as Farid’s favourite film. There is an unfettered nature to it that feels like it is compelled to take us somewhere new. “This resilience is something that is part of our way of working, thinking, conceiving and creating, and this is necessarily fruitful. There will be better fruits, better films, better artworks.”