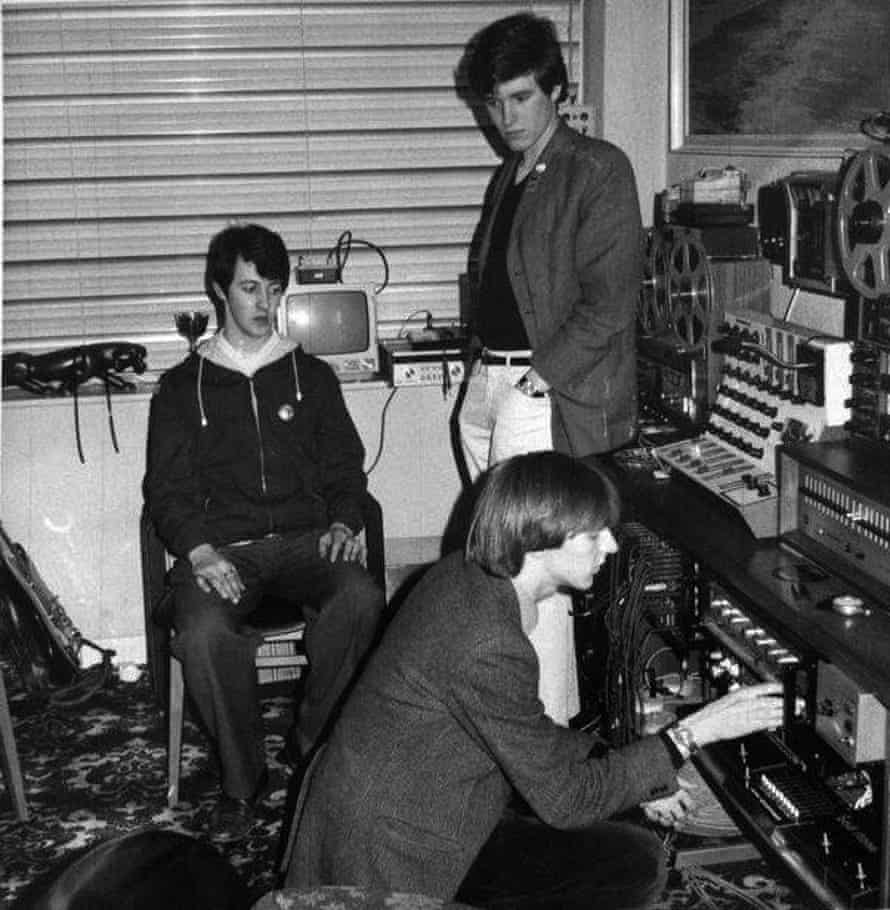

A band turning up for a session at Studio Electrophonique in the late 1970s could have been forgiven for thinking they had the wrong address. An ordinary Sheffield council house with a caravan parked on the driveway, it was semi-detached with deep pile carpets and a toy poodle with a bark like a wildebeest.

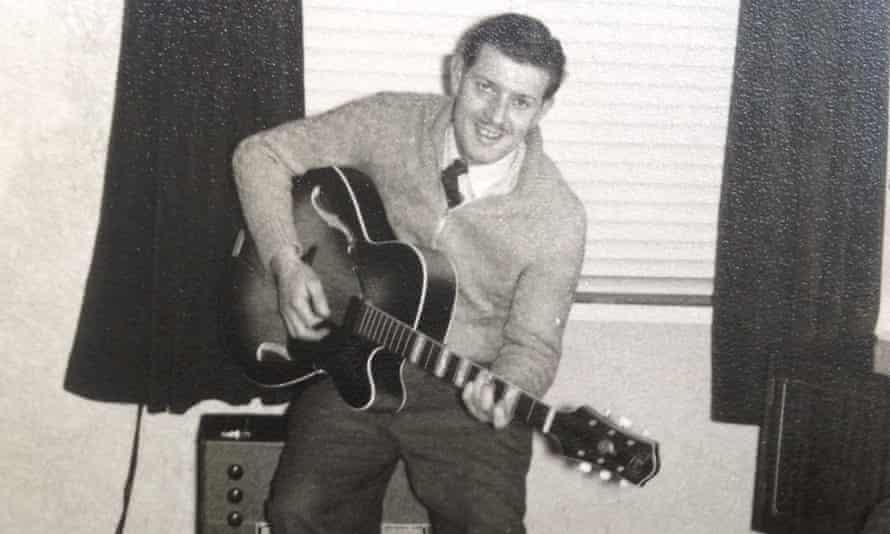

But behind the chintzy curtains, an RAF veteran and panel-beater called Ken Patten had handbuilt one of the most pioneering electronic studios in Europe. In return for a £15 recording fee, he helped some of Sheffield’s most important bands form their nascent sounds – from Pulp to ABC, Heaven 17 and the Human League, as well as less heralded acts such as the Doncaster Wheatsheaf Girls Choir.

Now, two former teachers from Sheffield have made a documentary celebrating “one of the great untold stories of British pop music”. Premiering at the Sheffield DocFest this week, they paint Patten’s home on the Ballifield estate in Handsworth as the unlikely crucible of Yorkshire’s electro scene and Patten its thrifty resident genius.

A Film About Studio Electrophonique is narrated by Sean Bean, who grew up in Handsworth. “I had no idea when my dad sent me around to Ken Patten’s to pay his garage bill that Ken had built his own creative world in his downstairs extension,” he says. “None of us knew that he was recording the sounds of space-age Sheffield or indeed that that space-age sound would become the future of British music.”

Martyn Ware, who went on to form the Human League and Heaven 17, recalled visiting with his first band, an experimental collective called The Future: “We knocked on the door and his wife was there. She said, ‘Oh hello lads’, and offered us a cup of tea and showed us into the front room and it was all chintz and voluminous armchairs and a coffee table with a four-track recorder on it. I remember going: ‘Where do we put the synths?’ I think he must have had some keyboard stands sitting on the deep plush carpet and I remember thinking: this is way too comfortable for recording something as avant garde as this.”

Though he specialised in electronic music, Patten would record anyone who answered his classified ads in the Sheffield Star. Jarvis Cocker, who made a demo with Pulp in 1981, remembers: “We turned up and he was kind of bemused. I don’t think he realised how young we were. I was the oldest in the band and I was maybe 17.” The demo led to the still unsigned band getting their first John Peel session on Radio 1.

“It turned out that the main recording place was going to be the bedroom. That was where the drum kit was set up. Our drummer, Wayne, went up there and I think we were in the kitchen but through some creative use of wiring he could hear us,” Cocker says.

“The thing that really impressed me was [Patten] turned on this portable little black and white TV and we could see the drummer, up in the bedroom on TV. This was something for communication but his wife had insisted on it to make sure people didn’t misbehave themselves in the bedroom.”

Cocker also recalls Patten’s pride in his homemade vocoder, which he cobbled together for 50 pence using two toilet rolls and old throat microphones pinched from fighter pilots in his RAF days.

Sign up to First Edition, our free daily newsletter – every weekday morning at 7am

The hour-long film takes the form of a detective story as James Leesley – a supply teacher turned solo artist who has adopted the stage name Studio Electrophonique – tries to track down Patten’s relatives and collaborators.

The pair recorded it all on an iPad “using a £20 microphone and edited it using a £3.99 app”, says director James Taylor, an English teacher who now does outreach work at Sheffield Hallam University.

Patten, who died in 1990, deserves to be better known, says Leesley: “I’ve asked a few people who have been around Sheffield music for about 30 years and they’ve never even heard the name Studio Electrophonique or even Ken Patten, so I guess that makes it one of the great untold stories of British pop music.”

A Film About Studio Electrophonique is available to watch online and showing at the Sheffield DocFest on Tuesday at 3.45pm.