In 2002, “Air Force Ones,” the third single released from St. Louis rapper Nelly’s second album Nellyville, became his third top 5 hit from that album, peaking at No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100. 23 years later, the song’s subject, the then-20-year-old Nike sneaker model, is still a staple of hip-hop style and street fashion, proving that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

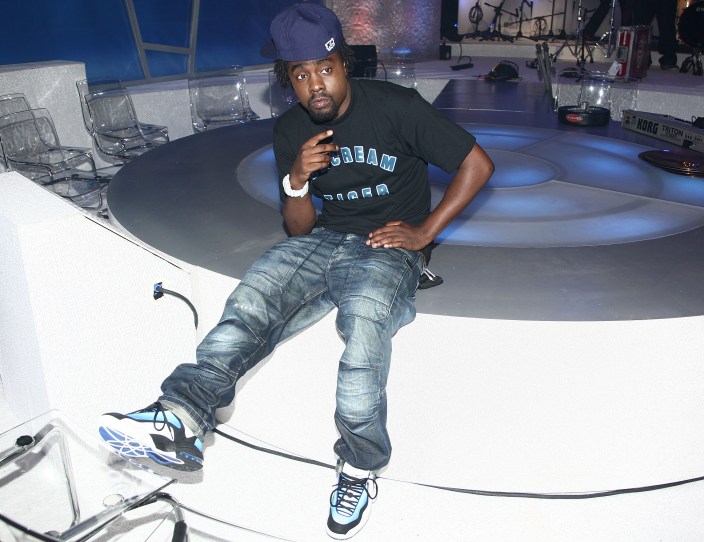

Over the past 25 years of the not-quite-so-new-anymore millennium, streetwear has gone through its fair share of evolutions. Yet, through it all, one element has remained the foundation of hip-hop style, and thus, of broader fashion trends: Classic sneakers. Whether it was the rapper brand, all-baggy-everything era of the early 2000s, the rise of the rap fashionista in the 2010s, or the return to looser fits and archival fashion in the past five years, our outfits have all been built from the ground up — literally — starting with what’s on our feet.

According to sneaker expert Jacques “Kustoo” Slade, this goes back even further, to the very roots of hip-hop as a culture. “Sneakers and hip-hop have had a tie back, obviously, as far back as I can remember, with Run DMC and ‘My Adidas’,” he recalls via Zoom. “We’ve always seen sneakers integrated into the hip-hop culture and lifestyle. Something as simple as the Fresh Prince [Will Smith, star of The Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air] and Martin [Lawrence, star of 1990s sitcom Martin] wearing Js on their shows. And if you’re tied to basketball culture at all, and the tie between basketball culture and hip-hop, you see threads of those storylines all come from a certain place.”

Slade would know; he was one of the earliest and most prolific of the second-generation sneaker culture documentarians of the 2010s, following in the footsteps of pioneers like Bobbito Garcia and Scoop Jackson in the ’90s. Writing sneaker-focused editorials for online publications like Complex, Hypebeast, KicksOnFire, and Nice Kicks, he had a personal hand in bringing light to a new wave of kicks enthusiasts, who helped make sneakerhead culture mainstream over the past 15 years.

While he agrees with the observation that retro sneakers have formed the foundation of style evolution since the early aughts, he notes that there have been mini-trends within that tradition, and likens this to the cyclical nature of fashion trends as a whole. “Everybody wearing Retro Jordans didn’t really pop off until early 2010, late 2000s. Before then, [Nike] Air Max had a run, and before that, it was big basketball shoes in the nineties. Now we’re back in this space where runners are becoming cool again. So, it’s cyclical, just like I think fashion is bringing those styles back. The shoe brands have stayed the same, but the clothing brands have changed.”

“So, the styles of those older brands that we rocked when we were wearing Jordans back in the eighties, a lot of those brands aren’t ‘cool’ anymore,” he observes, “But the sneaker brands have remained cool. So Nike, Adidas, Reebok, New Balance, those brands have kind of retained their cultural significance, whereas those fashion brands haven’t. And now the cycle of clothing that we see happening is the same things we were wearing during those times, it’s just that there are new brands now because those brands aren’t as cool as they used to be. So it’s the same cycle, just a different brand name on it.”

Megan Ann Wilson, one of Jacques contemporaries and colleagues in the 2010s sneaker blog explosion, concurs. Going by the sobriquet “SheGotGame” online, Wilson’s blog was one of the first to bridge the gap between legacy designer fashion and sneaker culture, and her work as a stylist has included clientele such as NBA players Andre Drummond and Stanley Johnson, NFL players Brandon Ghee and Tarell Brown, and commercial clients like Complex, BET, and Mitchell & Ness. This has put her in prime position to witness the connections between athletes and hip-hop firsthand.

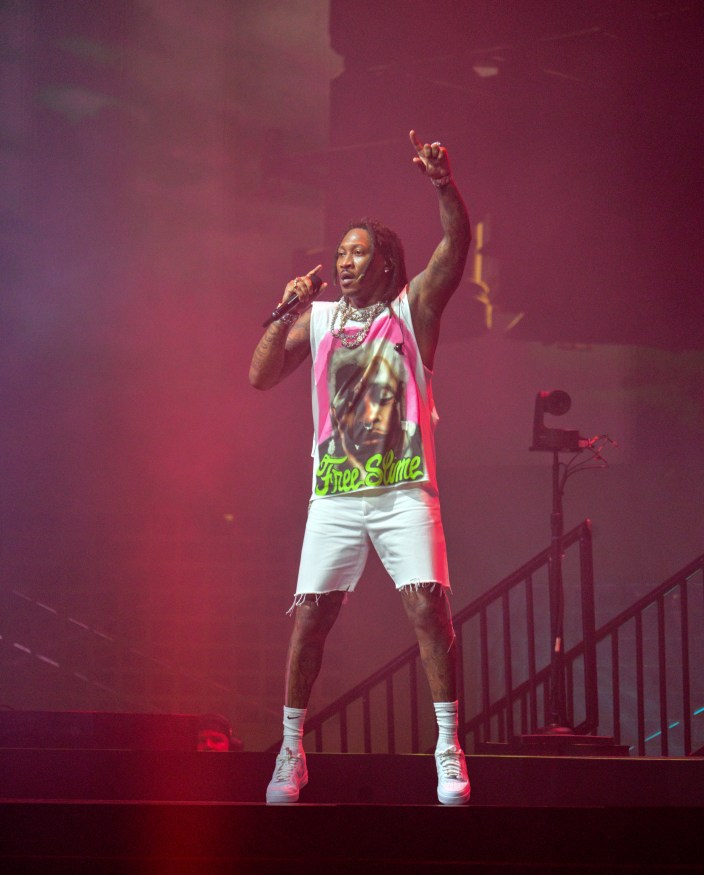

Assessing the past two decades of style evolution, she says, “I think the main thing is that we saw the commodification of fashion through hip-hop style.” For example, she notes that athletes and rappers alike now have entire teams of designers curating not just their looks, but their entire personal brands. “Now, it’s very rare that you talk to an artist that they don’t have a full team. And even if maybe they have stylists that work with other people, they also have a brand manager, or they have now labels. They have people who are working on the partnership side, they’re working on the brand partnership side, and we’ve seen that a lot in sports.”

The end result is a sense that personal touches have become lost in all that — but that sneakers remain a way for artists, athletes, and their fans to remain in touch with identifiers like regionality. “I think what people are missing from that era [the 2000s] — whether it’s the Bad Boy era or the Dipset era or the old Outkast videos — they’re missing this sense of artists having a personal touch on what they’re wearing rather than having them very produced.”

“Now, it’s so hard to know if these trends are merely manufactured, or are these 20-year-old rappers coming out really into Y2K fashion?” Megan wonders. “Or do they have a stylist that’s my age that’s like, ‘No, this is trending, you should wear it.’ So it’s changed a lot in how it’s packaged… Then with sneakers, I think we’re seeing that too, in that in the 2010s and even up to 2020, it was resale culture. Who has the most heat? Who has the most things? And now it’s become, what’s your collection? Where’s your style coming from? And I think a lot of the brands haven’t fully caught up to that. We had a customization era, and we had a very limited-run era. Now it’s like they’re putting everything out again, but what’s actually new, what’s exciting, or what’s also really someone’s style?”

In locating the answer, Wilson points to regional signifiers such as Air Force 1s, which weren’t only popular in Nelly’s native St. Louis, but were a staple of the Harlem, New York uniform in 2011, when ASAP Rocky began his ascent to stardom in both the hip-hop and high-fashion worlds (so much so that there was a minor kerfuffle online over it a few years ago when Rocky claimed credit for the popularity of 1s — or “Uptowns” as they are called, well, Uptown). “To me, I used to be able to know if I was running around New York, ‘Oh, I know that guy’s from Brooklyn because of how he’s dressed. I know he’s from the Bronx because of how he’s dressing,’ just because there was a very specific look. For me, [Nike Foamposites] are like a DC thing, but they’re also an Uptown thing.”

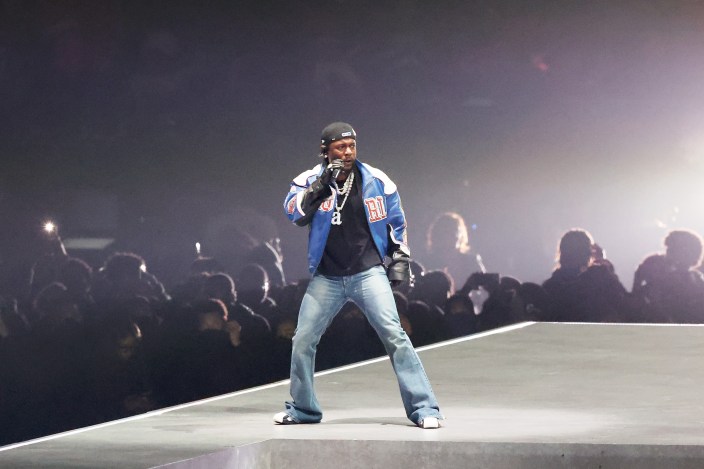

Both experts cited the same recent cultural touchpoint as an indicator of how hip-hop trends are evolving: Kendrick Lamar’s culture-gripping Super Bowl Halftime Show performance this past February. “Is hip-hop what Kendrick had on at the Super Bowl?” Slade wonders. “Would we consider that to be hip-hop where he had on semi baggy jeans with kind of bell-bottoms and one of them NBA champion leather jackets? Everything is so homogenous because we’re all seeing the same things, and there’s not a lot of opportunity for style differences to pop up from a certain region.”

While the jeans got plenty of attention, inspiring thinkpieces across the internet, most of us probably wouldn’t be able to grab archival classics at their usual price points. But you can always pair YOUR look with a fresh pair of kicks. In Kendrick’s case, StockX, the secondhand resale platform, which mainly focuses on sneakers and streetwear, noted a 400% percent increase in the average bids for the sneakers, a pair of Nike Air DT Max ’96, after the performance. Which just goes to show, in the modern era of hip-hop style, whether you’re chasing trends or pursuing self-expression, you have to start somewhere. And in the immortal words of Mars Blackmon: “It’s gotta be the shoes.”

Content shared from uproxx.com.