JRE / YouTube

Pop culture is haunted by ‘what ifs.’ What if they hadn’t died so young? What if they had more time? With John Belushi, those questions feel even heavier—because by the time of his death in 1982, he had already done so much.

By 1982, the Saturday Night Live star had already achieved a level of comedic immortality. He was Animal House’s Bluto, a role so full of anarchic energy that it cemented him as a Hollywood icon overnight. He was the co-founder of The Blues Brothers, a band born from a SNL sketch that became a chart-topping act and a cult-classic film. And on stage, he was something else entirely, a live-wire performer whose presence swallowed the room, whose physicality was as sharp as his wit. Ask anyone who came of age in the 1970s and early ’80s—he was a force of nature.

But by March of that year, John Belushi was dead at 33, found in a bungalow at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, a speedball of heroin and cocaine in his veins. It was a hard, ugly ending that invited scrutiny and sensationalism. And, in the case of Bob Woodward—the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who helped expose Watergate—it resulted in a bestselling but controversial biography: Wired: The Short Life and Fast Times of John Belushi.

To those who knew Belushi best, Wired felt like a hit job.

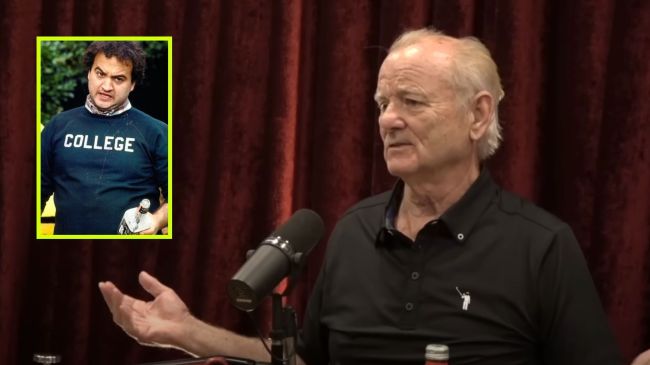

That includes Bill Murray, who was Belushi’s SNL cast mate, longtime friend, and fellow Second City alum.

He’s never forgiven Bob Woodward for it, even suggesting on The Joe Rogan Experience that Woodward, now 82, will have to answer for it someday.

“I Read Five Pages of Wired, and I Went, ‘Oh My God. They Framed Nixon.’”

Bill Murray is famously elusive—the kind of celebrity who exists as much in myth as reality. He’s been known to crash weddings, bartend unannounced at SXSW, and pop up in random places with a knowing smirk. “No one will ever believe you.”

He doesn’t do many interviews, let alone sit down for a sprawling, two-and-a-half-hour conversation. But when the topic of Saturday Night Live and John Belushi came up, Murray didn’t hold back by sharing his thoughts on Wired, which was published in 1984, just two years after Belushi’s death.

For decades, Woodward was considered one of the most unimpeachable journalists alive. His All the President’s Men reporting was critical in helping force Richard Nixon out of office.

But for Murray, reading Wired shattered that image. If Woodward could misrepresent Belushi so badly, what else had he distorted?

“I read like five pages of Wired, and I went, ‘Oh my God. They framed Nixon.’” Murray tells Rogan.

For Murray, Woodward’s reporting in the book was so wildly off-base that it made him question everything else the legendary journalist had written—even the reporting that brought down a sitting U.S. president.

“All of a sudden I went, ‘Oh my God, if this is what he writes about my friend that I’ve known … for half my adult life, which is completely inaccurate, talking to like the people of the outer, outer circle … what the hell could they have done to Nixon?’”

Watch the part of the Bill Murray / Joe Rogan interview about John Belushi on YouTube:

A Book That Did More Harm Than Good

Bob Woodward wasn’t just some tabloid hack. He was the Bob Woodward—the man who, alongside Carl Bernstein, had exposed the Watergate scandal and became one of the most respected investigative journalists in American history at the Washington Post. But when he turned his focus to Belushi in the early 1980s in the wake of the comedian’s untimely death, his approach didn’t sit right with those who had actually known the comedian.

The problem, as Murray saw it, was the sources.

“Wait a minute, you’re telling me that that guy over there … is telling you the facts about John Belushi? That guy, way the f** over there, is telling you who John Belushi is,” Murray says on The Joe Rogan Experience.

Belushi’s inner circle—his closest friends in comedy like Murray, the people who worked and lived alongside him—either weren’t interviewed at all or were marginalized in the narrative. Murray, for one, refused to participate, sensing from the start that it was going to be a bad-faith effort.

“I didn’t want to have anything to do with it. I would have nothing to do with it. I didn’t like it. It smelled funny from day one,” Murray says to Rogan.

He wasn’t alone in that feeling. Dan Aykroyd, Belushi’s Blues Brothers co-star and best friend, hated Wired so much that when Hollywood tried to turn it into a movie, he refused to be involved, famously quipping that it would be more appropriate “as a horror film.” Belushi’s widow, Judy, condemned the book’s portrayal of her husband, calling it “cold” and “merciless.”

Murray agrees.

John Belushi, The Lightweight Party Animal

John Belushi’s death was already a media spectacle in 1982 and 1983, but it escalated when the late Cathy Smith, his companion on the night of his overdose, became the center of a criminal investigation. Smith, a former Sunset Strip groupie and drug dealer, initially gave an interview to The National Enquirer admitting that she had injected Belushi with a fatal speedball mixture of heroin and cocaine. That confession led to her extradition from Canada and a high-profile trial, during which she was charged with second-degree murder before ultimately pleading no contest to involuntary manslaughter and drug charges in 1986. She served 15 months in prison, but by then, the damage had been done by Woodward’s book.

Murray doesn’t deny that Belushi partied. He doesn’t sugarcoat the fact that drugs were a factor in his death. But he also believes Wired reduced a brilliant, complex human being to a cautionary tale.

“He made people’s careers possible. Mine would be one of them. All the people that he dragged to New York … He took over New York, and he dragged all of us from the Second City to New York.”

Belushi’s influence stretched far beyond SNL. According to Murray, Belushi was pivotal in building other people’s careers, including his own.

“There are musicians, and lots of them, that will thank Belushi for the revival of the blues… There are all these venues that wouldn’t have existed without Belushi, like the entire House of Blues chain.”

And yet, Wired painted Belushi as a reckless addict with an inevitable demise, something Murray strongly pushes back against.

“He was a short hitter. Guy could only drink like four beers, and he was drunk. So the idea that he died of an overdose is hilarious. Like, that’s what my brother said. He said, ‘What did he have, four beers?’ Because he was not really much of a drinker.”

Murray believes Belushi’s overdose wasn’t the result of a long downward spiral, but an awful, singular mistake.

“It was a speedball, yeah. And I believe, to my knowledge, it was like the first speedball he ever had.”

This isn’t to erase Belushi’s struggles, but to counter the narrative that he was doomed from the start. Murray, along with others in Belushi’s circle, sees his death as a tragic, preventable accident—not a foregone conclusion.

“He did a lot of things for people … He was absolutely magnetic.”

That’s the Belushi Murray wants the world to remember, not the one Bob Woodward wrote about.

A Bigger Conversation About Trust in Media

Joe Rogan, a longtime critic of mainstream media, didn’t miss the opportunity to connect Murray’s criticism of Wired to a bigger issue: trust in journalism itself.

Joe Rogan: “Once you see it from something that you know, you know, once you see propaganda or bulls*** from someone that you know, and you see a distorted perception, it really … opens your eyes to the fact that a lot of the things you read are horsesh**.”

And Bill Murray isn’t alone in his skepticism. Ben Dreyfuss, journalist and son of actor Richard Dreyfuss, had his own family’s brush with Wired—and it was personal.

Dreyfuss’s mother was dating Belushi when he died and, according to him, was the only person to have seen a video Belushi filmed the night before his death. When she refused to hand it over, Woodward allegedly harassed her relentlessly, to the point where Richard Dreyfuss had to get his lawyer, who happened to share a client with CBS, where Woodward was a contributor, to force him to back off.

As Dreyfuss put it bluntly:

“As retaliation in that book he calls my dad a drug addict (true) and my mom a ‘hard-faced woman’ (false).”

His frustration with Woodward never faded. Years later, at a White House Correspondents’ Dinner, he recalls seeing Woodward honored and resisting the urge to be polite.

“The truth is my mom is such a nice woman and he was really bad to her and he can f**k himself. But everyone was like ‘oh wow Ben not nice.’”

He doesn’t pretend to be objective about Woodward.

“I’m sure Bob Woodward has done some good work in his life, but he was very unfair to my mom and I don’t pretend to be objective about him. He can go f**k himself.”

The fastest way to blackpill anyone on journalism is to have the press cover something they personally experienced or know very well.

— Jared Jensen (@jared_jensen75) March 2, 2025

The conversation hit on something larger than Belushi’s legacy and his shocking death, which obviously had a profound impact on friends like Bill Murray. It makes you think about narratives get shaped, and how people with the loudest voices in media get to define the truth. Back in 1984, Woodward’s Wired was treated as the definitive account of Belushi’s life. There wasn’t social media to drive discourse, nor were there podcasts where someone like Bill Murray could challenge it in real time to a huge audience.

Joe Rogan: “Back then, … there’s no other venues for people to express themselves. Back then, it was like he writes the book, he does the interviews for the book. This is the narrative.”

Murray had spent plenty of time around journalists in the 1970s and ’90s, including his friend Hunter S. Thompson, so he wasn’t naïve about the storytelling choices they made.

“History is hard to know because of all the hired bullshit,” Hunter S. Thompson wrote in Hell’s Angels. “But even without being sure of history, it seems entirely reasonable to think that every now and then, the energy of a whole generation comes to a head in a long fine flash, for reasons that nobody really understands at the time—and which never explain, in retrospect, what actually happened.”

But reading Wired was a wake-up call: even the most trusted reporters could get it completely, irrevocably wrong.

“Bob Woodward, like, one of the squarest guys in the world, gets to tell the story of what it was like to live in New York City in the ’70s? Really? In the late ’70s and ’80s? Like, he knows the story? Come on.”

Content shared from brobible.com.