You’re looking at a screen capable of displaying anything imaginable, from live footage of places continents away, to interactive simulations created by the device itself. You are currently using it to read text.

This would surprise someone from a century ago, who figures they’re able to do the same basic thing by looking at a sheet of paper, but it makes sense. The entertainment we like isn’t decided by the level of technology we can access. And people, in fact, made do pretty well back when their tech was much more primitive.

The First Video-on-Demand Services Used a Coin-Operated Box

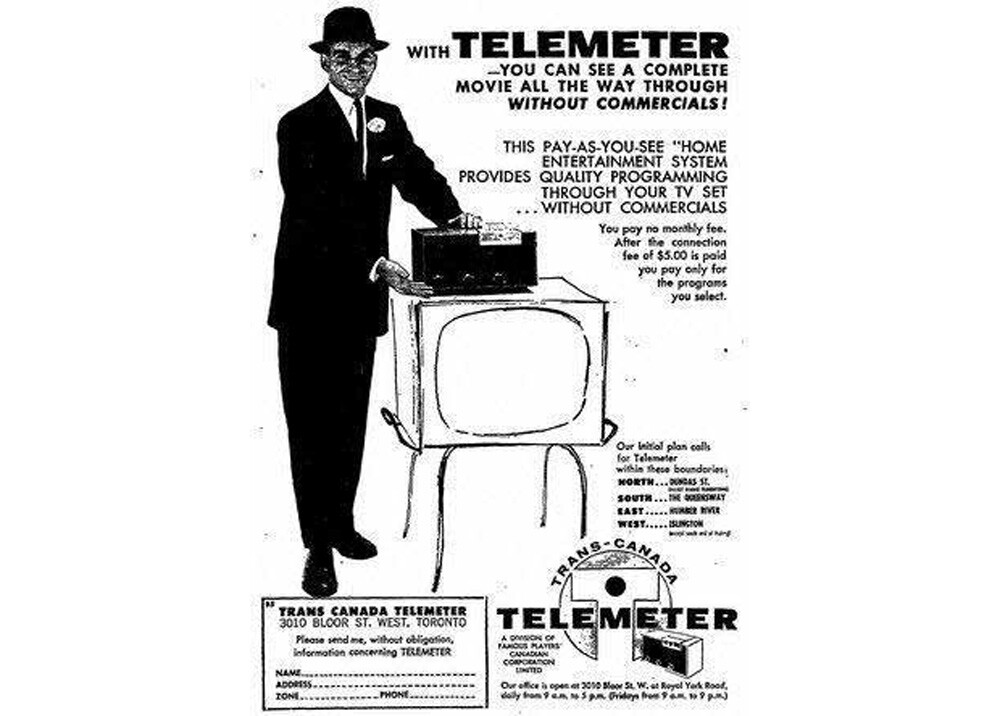

In the 1940s, public places like bus stations sometimes had televisions you could turn on for a specific amount of time by inserting coins. This was a logical evolution of the nickelodeon, an older device where people inserted a coin to watch a short film. Then companies had an idea: What if they attached coin boxes like this to the TVs people have in their own homes, so people can watch using this same pay-per-view style while relaxing in their living room?

Obviously, if you owned your own TV, you could watch it as much as you wanted, so attaching a coin-box for access didn’t make much sense. But this new service, called Telemeter, gave people temporary ad-free access to additional stuff, like movies and sports broadcasts. It delivered this programming through a dedicated coaxial cable, much like the cable service we all know, but rather than subscribing per month or ordering stuff by phone and getting billed, you dropped coins in like a vending machine.

Each broadcast cost $1, which is around $10 in today’s money, and the average family who subscribed to Telemeter bought about 10 of these each month. That’s a lot more expensive than any streaming service you can pick today, while offering you far less, but each program cost less than modern PVOD. On the other hand, setup cost a lot. The box cost $250 in today’s money, while installing the cable could cost $5,000.

Telemeter debuted in 1953. It didn’t last. Though people were into it, theaters and networks didn’t like the competition, and they successfully pushed for the service to shut down. Pay-per-view would return later, but on the networks’ terms this time.

People Added Flash to Cameras Using Pocket Explosives

When you take a picture with your phone, you may or may not need to use a flash, because your camera’s sensor is pretty sensitive to light. The farther back you go in time, the more light cameras needed. If you go really far back, it was impossible to take in all that light without leaving the shutter open for a long exposure. Later, we were able to use electric bulbs, but they needed high voltages, and people ran the risk that their camera battery would fail and the bulb wouldn’t light.

The solution? Explosives.

Explosives can burn bright, as you might have noticed if a firework has ever whizzed directly at your eye, and in the 1970s, General Electric sold a safe and controlled explosive device for your camera called the Magicube. When you took a picture, the camera would mechanically strike an explosive compound of fulminate. The fulminate exploded and ignited foil made of zirconium, and the whole thing was contained in a glass bulb. The foil burned away in a split second. In other words, it happened in a flash.

The Magicube contained four flash bulbs. Each time you used it, the device would rotate, and a new compartment would be ready to explode for your illumination. Once you’d used it four times, you had to throw it away, and the price worked out to more than a dollar per photo in today’s money — just for the flash.

Also, there was the slight risk that the explosive would explode a little too much and send glass flying forward. Subjects were advised to stand at least five feet away from the camera, for safety reasons. Selfies were therefore not practical. Some might say that was a plus.

The First Streaming Music Predated the Recording Industry

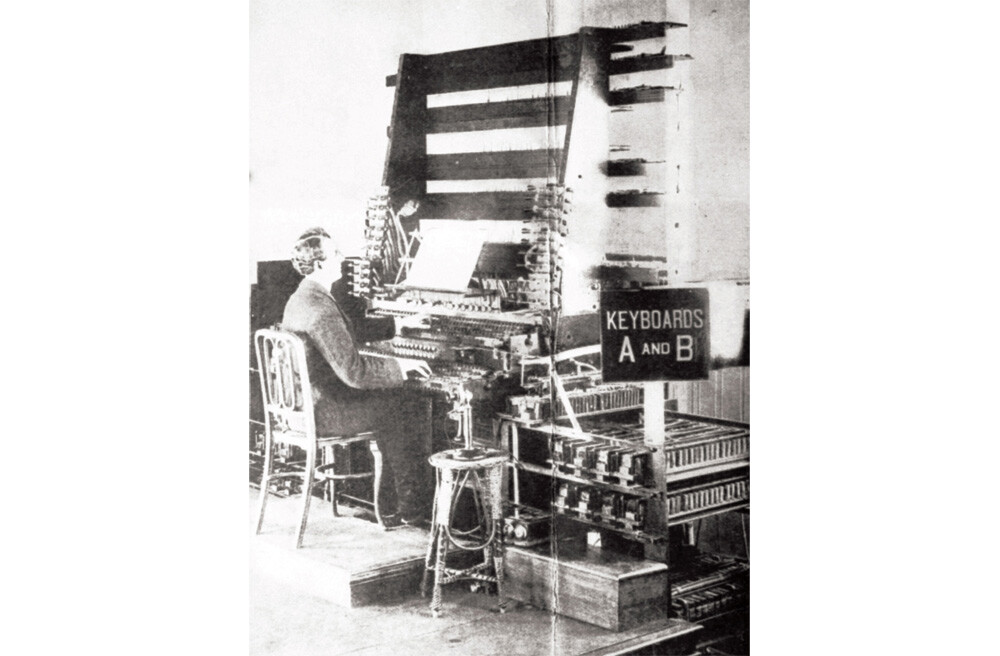

The current incarnation of music streaming debuted as an alternative to owning (or stealing) your own individual recordings. When the first music streaming service was conceived of in 1893, buying recordings wasn’t an option at all. The phonograph existed as an invention, but people more often bought songs by buying sheet music, which they had to play and perform themselves. So, when a new invention called the Telharmonium offered to let you hear music in your home, piped in over the phone, that sounded pretty amazing.

This music was performed live at a venue called Telharmonic Hall in New York City. It wasn’t a normal band or orchestra, whose sound was picked up by a telephone mic. This was a new electronic device called a synthesizer. Unlike the keyboards that we call synthesizers today, four different musicians operated it at once, with multiple technicians whacking at keys and another controlling volume. Rotating shifts of men played it 24 hours a day. The thing weighed 200 tons.

Radio eventually killed the Telharmonium star, but for a few years in the 1900s, people gladly paid 20 cents per hour ($7 in today’s money) to listen to its music. As a sign of how far back in time this was, Mark Twain was an early adopter. “Every time I see or hear a new wonder like this I have to postpone my death right off,” said Twain, which should absolutely be your reaction every time you see new tech.

Hackers Sent Out Dirty Limericks Over Telegraph

Radio dealt a blow to another industry as well: wired telegraphy. So, when Guglielmo Marconi was introducing the world to his revolutionary wireless telegraph system, the international Eastern Telegraph Company sought to sabotage him. In their desperation, they turned to a magician.

His name was Nevil Maskelyne, and when he wasn’t performing stage magic, he was tinkering with technology. He now built his own 150-foot radio tower to successfully tap into a supposedly secure Marconi transmission. Emboldened, he next headed to a public exhibition that Marconi was holding in London.

At this 1903 event, Marconi was supposed to show off a broadcast he was sending in from 300 miles away. Instead, the broadcast was preempted by a word or Morse code inserted by Maskelyne over and over — the word “rats.” Then came a longer interruption, consisting of poetry, about Marconi: “There was a young fellow of Italy, who diddled the public quite prettily.” Next came a dirty pun from Shakespeare. Sources don’t say which one, but it was probably about a dick.

via Wiki Commons

Maskelyne was one generation of a larger family of magicians, by the way. His son Jasper used his skill at misdirection to design miniaturized equipment to distract the Nazis into attacking fake targets. Nevil’s father John invented the coin-operated toilet. That last feat might not sound as much fun, but getting you to pay for stuff coin-by-coin is the foundation on which all of entertainment lies.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.