The rules of survival in Hollywood have always fascinated me. “Consistency is the key – always present yourself to studios as a total bitch,” Bette Davis once confided. “Never delude yourself into thinking that a star can become a loyal personal friend,” advised Billy Wilder. “Since studios always lie, a producer’s mandate is to come up with bigger lies,” said David O. Selznick.

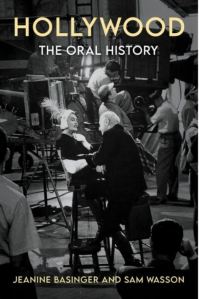

As a collector of Hollywood war stories, I was pleased this week to discover a new book (741 pages) with the intimidating title Hollywood: The Oral History – one that has greatly expanded my inventory of intrigue.

Over the course of the last 50 years AFI (the American Film Institute) has semi-secretly recorded, and now published, interviews with accomplished stars and filmmakers, thus creating an intimate Hollywood history told in first person (HarperCollins is the publisher).

Approaching a book of this size as summer reading, I decided to focus not on thoughtful analysis, but rather on combat. The AFI’s collection of interviews is thus akin to dropping by a cocktail party with the likes of Katherine Hepburn, Natalie Wood, Olivia de Havilland, Jack Lemmon, Wilder and George Lucas.

They’re all at their candid best in exploring their rivalries and conflicts. Our “native guides” in the AFI book are Sam Wasson and Jeanine Basinger, two gifted film nerds who curated the collection (he wrote The Big Goodbye and she is a film historian and professor at Wesleyan).

A case in point: Was Marilyn Monroe really emotionally troubled? To contemporaries, her depression was a device. “Marilyn always succeeded in getting her way by feigning breakdowns,” suggests Lemmon, her Harvard-educated colleague.

Was Humphrey Bogart unapproachable both on set and off? No, but by repeatedly snapping “cut the crap” to everyone he survived in “a profession not suitable for grownups” (his words).

How did superstars of the 1930s and ’40s cope with restrictive studio contracts? “They fucking owned us – you learn to deal with it,” said Wood.

Signed as a kid and surviving nine Andy Hardy movies opposite Mickey Rooney, Ann Rutherford concluded, “The only way to find decent scripts is to steal them from make up artists or costumers.”

De Havilland ultimately became so angry over her studio pact that she broke the rule – she sued Warner Bros and won: “They owned me and traded me like a commodity,” she said.

Only a few stars (like Cary Grant) emerged from the fray loved or admired by colleagues. Some were regarded as rudely aloof (Bing Crosby), hopelessly unpredictable (Judy Garland) or just goofy (Montgomery Clift).

Coping with mood swings, directors of the period each had his strategy for dealing with narcissistic intrigue. “I stayed away from stars on a social level –as far away as possible,“ said Wilder.

“If you run into an actor’s personality problem, an expensive dinner and lots of wine is the only way to melt them,” says Elia Kazan.

Initially terrified at the challenge of directing Bette Davis, Ron Howard humbly pleaded, “Please just call me Ron, Miss Davis.” To which Davis snapped: “First I’ll decide whether I like you or not.”

The most effective way to deal with an argumentative actor was to say ‘How about shutting up?’, advised George Cukor, the gifted director who was fired in the fourth week of Gone With the Wind. His style didn’t please Clark Gable, who felt Cukor was basically “a woman’s director.”

Selznick, the producer, brought in first Victor Fleming, then Sam Wood, then Fleming again to pacify Gable as well as Vivien Leigh and de Havilland, the ferocious sister act.

So overall, did the studio system in its prime work for its illustrious employees? The film factories were each turning out between 40 and 80 films a year, and commanding vast staffs of players. Fox had 76 writers under contract and MGM had deals with 250 actors.

But while the imperious studio bosses like Louis B Mayer or Harry Cohn made the big decisions, they lacked the structure to deal with talent. A novelist like William Faulkner would sign with Fox, then disappear for a year and still pick up weekly studio checks. Remarkable talents like George Bernard Shaw or F. Scott Fitzgerald would wander studio lots and but no one knew how to utilize them.

Everett

Studio publicity departments run by tyrants like MGM’s Howard Strickling would freely reinvent the careers and personalities of prospective “talent.” Hedy Lamarr, who was born Hedwig Kiesler, was assigned the name of a deceased actress to become her new name. She protested meekly but no one cared.

Leslie Caron could never succeed in posing for a studio photo without the presence of a cat, but she hated cats. Lemmon was signed to test for a role as a serious businessman, only to be cast as a young comic. Nelson Eddy, a singer-actor, remained under a lavish contract at MGM for five years, but was never asked to appear in a studio movie.

To be sure, many entertaining movies emerged from the chaos, along with expensive duds. Thus the AFI book opens with a quote from director Ridgway Callow, declaring: “Hollywood is the cruelest and most despicable town in the world.”

Co-author Wasson, having waded through the treasure-trove of interviews, emerged with a different perspective: “Hollywood in its prime was a happy and productive place. There was always combat behind the scenes but pride in one’s work and a sense of community carried filmmakers through.”

Mind you, I wasn’t personally there at the time.