How many stories are hidden in the murals of Diego Rivera? What was it like to witness the creation of a modern Latin American nation, to sit in the classrooms of stridentism and surrealism? To travel in a tram through a capital city illuminated by the embers of a recent revolution yet disrupted by periodic presidential assassinations?

These are just some of the questions that brought a young team of video game developers back 100 years to Mexico, 1921.

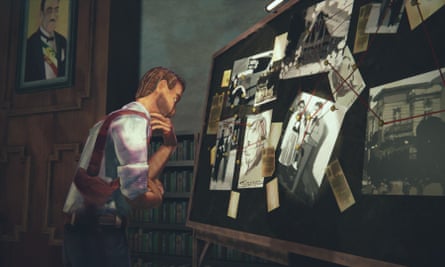

Set in Mexico City following the Mexican revolution, Mexico, 1921: A Deep Slumber is an ambitious new docu-game from historical game factory Mácula Interactive. Weaving together watercolour skies and vibrant streetscapes with political history, national archives and affective design, the game takes players to a decadent and decisive decade in the country’s history as a timely hero: a journalist.

Mexico, 1921 is played from the perspective of Juan Aguirre, a 22-year-old from the nearby state of Puebla who moves to Mexico City after the election of President Álvaro Obregón in 1920. There, he finds work at the newspaper El Unilateral – a nod to El Universal, the daily circular founded in 1916 that, starting in 1922, offered a supplement dedicated exclusively to news photography and illustration. With a new leader in office, the winds of change are lifting the curtain on the desires of a multicultural society, and a new act is under way in Mexico.

Gameplay takes place from 1921 to 1928 as the nation reconstructs itself following the seven-year civil war. Offering respect for the new constitution, a public education programme and support for the rural working class, the political project of Obregón inspires an air of rebirth. But the commander-in-chief also accumulates a great deal of power, and public opinion is easily manipulated by what gets printed in the press.

Armed with a typewriter and a medium-format camera, Aguirre is tasked with becoming the best-informed resident of the city so he can break the news, trail the trajectories of power and gather the chisme – gossip – that will later help him solve the assasination of Obregón.

“The game is structured in such a way that it touches, symbolically, on very particular realms of Mexico: its institutions, its culture, its society,” says 32-year-old creator Santiago Pérez. With a background in film-making, Pérez wrote the first draft of the script as though it were a movie, later building up a diverse studio with backgrounds in film production, cultural management, screenwriting and history. Not one had previously worked on a video game.

“In 1920, the press was fundamental for shaping the conversation,” Pérez says. “Our main character being a journalist opens the door to those spheres.”

In collaboration with the National Newspaper Archives, the “analog” team – made up of narrative coordinator Pedro Álvarez-Luna, game director Paola Vera and scriptwriter Iñaki Pérez – referenced photographs from the period, journal entries written by intellectuals and story after story from the press to construct a historically accurate plot.

“We’ve tried to give the game a historical narrative that is able to represent all of the relationships and dynamics that existed at the time, such as the day-to-day, how people talked, how they related to each other … for it to be an exciting story, that people can identify with the character and get involved in a personal way,” says Álvarez-Luna, 26. “The Mexico we know today was invented at this time, the great idea of mexicanidad [Mexican-ness] was created and crafted in this era. This is when the project of Mexico was starting to take form.”

Vetting sources in the halls of the Secretary of Public Education building, asking for an off-the-record interview in the Zócalo plaza and pursuing a diversity of voices are some of the skills you must develop as Juan Aguirre. Metiche, or nosy, mode illuminates certain pieces and objects of the environment a la Nancy Drew; hints scattered throughout the scenes may offer an interesting conversation or the opportunity to take a front-page photograph, or suggest a new location from which to eavesdrop on government officials.

Mexico registers an attack against a journalist or news agency every 16 hours, and the primary aggressor is the Mexican government. Only within the last few decades, however, did journalism in Mexico become so precarious, and the post-revolutionary period in Mexico is seen by many historians as an illustrative point of comparison. The aggression towards and stigmatisation of the press that began to emerge were largely the making of the country’s then-dominant political class, which eventually formed the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

“It’s crucial to rescue the figure of the journalist,” says scriptwriter and historian Iñaki Pérez, 27, “by showing this very human aspect of Juan, a person with a professional duty to fulfil , and by differentiating the job of journalist from the surrounding industry.”

In 1921, “the reading of newspapers was reduced to a very limited circle of businessmen, politicians, and intellectuals,” says Dr Bernardo Masini, historian and provost for research and graduate studies at Guadalajara’s Institute of Technology and Higher Studies (Iteso). “The political class was very interested in protecting its image before this small but influential circle. Obregón said very openly that there was freedom of expression, and the press showed its gratitude – what Obregón got in return was journalism in his favour,” says Masini, who has written a book on the role of the press during the presidency of Óbregon.

“When we talk about the great PRI, it’s this authoritarian, strong, repressive party,” continues Pérez. “The PRI was this because it co-opted the whole country: the teachers, the telegraph operators, the railroad workers, the students. I think this game can break that mould and let people take in this moment of history in a different way.”

after newsletter promotion

During the course of his daily work, Juan interacts with historical props – period magazines and novels, a radio tuned to a poem – as well as people, politicians and artists such as the muralist José Clemente Orozco, the painter Roberto Montenegro and the surrealist lovers Dr Atl and Nahui Olin. The game’s 35 historical figures also include Félix Fulgencio Palavicini, founder of El Universal; José Vasconcelos, Mexico’s first minister of public education, and Esperanza Velázquez, one of the first women to report and write the news in Mexico.

With the help of the Museum of Popular Art and Museo Casa Estudio Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo, the game’s designers built locations that function like museums where the player can find folk art and Mesoamerican artefacts, and learn about their history. Players can participate in the country’s first centenary celebration, attend an exhibit at the original Cafe de Nadie or wander the Convent of La Merced, a 16th-century colonial cloister that is today closed to the public.

“To me, the magic of the game is not the game itself but the things that happen after playing the game,” says game director Paola Vera, 30. “Its value is in the new ways of coexisting with art and history.”

Mexico, 1921 is slated for release in early spring 2024, ahead of Mexico’s presidential election. Mácula hopes that Mexican players find that it connects them to their past, but also that they might apply this historical thinking to their present.

“Aside from [people] rediscovering details in their own world, [I’m curious] to see what kind of interests the game awakens – the way in which players relate to things like the press, the handling of information, their role as a citizen as well,” says Álvarez-Luna.

“It’s a milestone for independent games in our country and in Latin America,” says Blanca Estela López, professor of game psychology and design at SAE Institute México and the Metropolitan Autonomous University. “There are a lot of games out there that portray Mexican characters, but rarely do we see Mexicans represented in the way we think we should be represented. Having more games like this is important because they reflect the voice of the creators.”

The team has since showcased the game at the London Games Festival, Latin American Games Showcase, Latinx Games Festival, Festival A Maze in Berlin, Pixelatl, IndieCade, Game Connection, Maquinitas (Ventana Sur) and last year’s Fantastic Pavilion at the Cannes film festival.

“So many people said we couldn’t do it, that it’s a bad idea,” remembers Vera. “The suggestions were: ‘Make a small game and finish it,’” adds Santiago Pérez. “We ignored the first and followed the second. In two and a half years, not only have we made video game, but we feel we have operated like a school. We are forming an industry.”

Álvarez-Luna says: “One of the lessons of the game is that the decisions of one person, or the ambitions of a group, or the clash between two groups – it makes good gossip, but the people who are affected are regular people. I hope that Mexico, 1921 teaches players to be more sensitive to nuance, to be critical and to be awakened by this – to dig at things.”