In a nameless town on the border of urban and rural life, at a nondescript high school like any other, arrows pierce through the idyllic landscape, hitting their targets and echoing out across a grassy field. The martial art of kyudo, Japanese archery, is at the center of Kyoto Animation’s Tsurune. The anime is currently at the end of its second season, Tsurune: The Linking Shot (which you can watch on HIDIVE), and while it may sound like any other sports anime with a bit of coming-of-age drama for spice — a tried-and-true genre of the medium — Tsurune pulls the viewer into a nostalgic dream world that feels vaguely like a memory of a life you may or may not have lived. The beautiful visual language of the show creates a longing to connect, a desire to reach back and relive the warmth of a memory that may or may not be yours. Nostalgia par excellence.

Tsurune is a beautiful show. The team at Kyoto Animation has poured its hearts and souls into making this show look amazing. Whether it’s the high-action shots of arrows in flight or the attention to detail in the background art that brings a local sports center or a high school classroom to life, there is an energy that pulses through Tsurune in both the intense narrative moments and in everyday scenes. Minato Narumiya’s journey back to kyudo after a tragic accident is made all the more powerful because of the care put in by series director Takuya Yamamura and his talented staff.

Telling a sports story in anime can be a relatively straightforward exercise. Your youthful group has a goal, usually to compete in a national competition, and they grow and experience life on their way to that goal. There is often a rival who is better at the sport than the story’s lead characters. Tsurune has all of these elements. Minato and his fellow Kazemai High kyudo club members are aiming for the national title, but in their way stands Shu Fujiwara and the private school kids of Kirisaki High. Yamamura storyboards these cliched elements perfectly, but they’re done in service of a greater philosophy, tying kyudo to something more, heightened by the incredible quality of the animation. Most anime won’t blow the budget on making a train station look photorealistic, but Tsurune does. Art director Shoko Ochiai has been creating gorgeous background art for years with Kyoto Animation, but Tsurune is the first project where she has been at the helm for art direction. Her time spent perfecting her craft on other Kyoto Animation shows like Violet Evergarden and Sound! Euphonium shines through here in Tsurune’s superbly composed scenery.

Image: Kyoto Animation/Sentai Filmworks

In the process of becoming a beautiful sports anime, Tsurune also taps into the particular emotional resonance of restorative nostalgia. When we think of nostalgia in a modern (mostly Western) framework, we envision remakes of popular ’80s or ’90s TV shows, or taking the aesthetics from previous eras and remixing them in the present to create something with a retro vibe. This is known as reflexive nostalgia, as it relies on the individual consumer’s feelings toward the nostalgic cultural objects being paraded in front of them. It is a relationship between you, your feelings, and the thing. Does seeing the original cast of Mighty Morphin Power Rangers together again get you up in your feels, reminding you of your childhood? If so, that’s reflexive nostalgia.

In an anime like Tsurune, the nostalgia you are connecting to isn’t necessarily yours alone. It’s linked to a collective set of nostalgic ideals, which often take the form of some kind of national sense of identity. It is working to restore something feared to be lost, or in the process of being lost. In this case, it’s a Japanese identity being swept away by modernity and the influence of globalization.

Restorative nostalgia in Tsurune is everywhere, as the show is steeped in a specific idea of what it means for a town to be a Japanese town. To be a person living in that Japanese town. To know deeply the feeling of being in that Japanese town. Crucially, it is that third part, the feeling, that Yamamura and his staff excel in. And it presents itself in ways both obvious and subtle.

First is the setting itself: The nowhere-but-everywhere town. Tsurune is set in an unnamed town based on actual locations in the very real city of Nagano. A show that wants to revive the classical idea of a Japanese identity is never set in Tokyo. The sprawling world city is far too cosmopolitan to be the setting that aesthetic restorative nostalgia needs to flourish. Kyoto Animation knows this, and the studio has been using real-world locations that exist on the border between urban and rural life for years. The 2012 coming-of-age drama Hyouka was based on the city of Takayama in Gifu Prefecture. 2013’s Free! used the town of Iwami in Tottori Prefecture (Japan’s least populated prefecture) as the setting for its “sexy boys do sexy swimming” anime. I once visited the city of Nishinomiya to see locations from Kyoto Animation’s 2006 classic The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya. My Japanese friend was thoroughly confused as to why I had to visit this boring suburb between Kobe and Osaka. Even after an explanation, he still didn’t get the appeal.

Image: Kyoto Animation/Sentai Filmworks

By setting anime in a town like this, the balance of nature, cultural tradition, and modernity forms a perfect nostalgic ratio that maximizes restorative potential. Tsurune’s nameless town is an even more powerful example of this phenomenon, as it allows the viewer to imagine the series could be set anywhere in Japan. While there are intrepid anime location hunters who run blogs and post on Twitter with their findings, for the general viewer, the anonymous anywhere helps them to identify with the themes of the show, as they are less likely to get hung up on the particulars of the city in the background.

Art director Ochiai and frequent collaborator Azumi Hata, who serves as Tsurune’s color designer, have a great eye for making these unremarkable everyday places into lived-in works of art. They share a love of giving age to the objects in their animated worlds, capturing that worn-in, authentic feel of places and spaces. When the series flashes back through Minato’s years of kyudo practice at home, the wear and tear on the hardwood shows through. It’s a visual manifestation of a memory that, for Minato’s father, conjures up feelings from the past. Touches like this make the setting of Tsurune intentionally, beautifully nostalgic. It happens everywhere in this show. A school hallway with dust particles filtering through sunlight, the local shrine draped in maple trees, or even the vending machines in front of the train station at sunset call out to the viewer, perhaps to jog memories of time spent in these spaces in one’s youth, or perhaps to create a link to a particular aesthetic ideal that someone in a one-room apartment in Tokyo’s concrete jungle may have lost touch with.

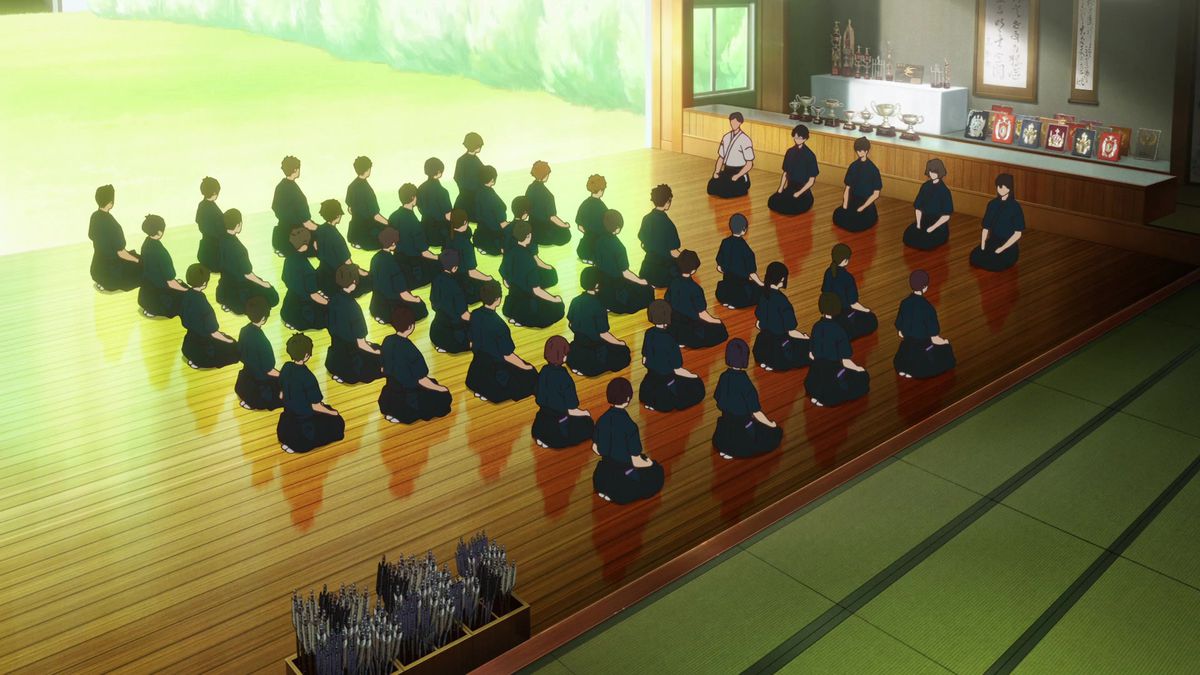

When layering the martial art of kyudo on top of this stunning background, Tsurune amplifies the nostalgic pining for a national identity by centering the story around a Japanese art with centuries of history. Kyudo has evolved through Japan’s history from being taught as an art of war to today, where it is taught as an art of discipline. There is a spirituality to kyudo that might be vaguely connected to Buddhism or Shinto (though never explicitly either), and that spirituality and philosophy are seen through the narrative and the show’s aesthetic motifs. Yamamura makes sure to highlight the precise movements and the particular aesthetics associated with kyudo in Tsurune. Finding beauty in the pulling taut of a bow or in the ritual steps an archer takes entering the archery hall. The sound of an arrow hitting a target, the ruffling and fluttering of the traditional hakama pants, and the sliding of split-toe tabi socks on waxed hardwood floors are all presented as part of this nostalgic package.

Image: Kyoto Animation/Sentai Filmworks

Once the narrative focus on kyudo philosophy and the lives of high school boys is established, it’s then that Ochiai and her team can go to work with aesthetic flourishes and accouterments to heighten its messaging. Cherry blossoms gently falling, cicadas chirping, and mysteriously opportune gusts of wind signal that closeness to nature, while the clattering of a can of coffee from a vending machine, the shopping street with mom-and-pop restaurants and storefronts, or even the quiet neighborhood street Minato lives on are made impossibly beautiful, rendering the everyday extraordinary. It fuels a nostalgic longing for the mundane.

There is a stubborn pride to this idea of a uniquely Japanese aesthetic, and Kyoto Animation is determined to keep it alive in Tsurune. The show is a coming-of-age drama, nestled in a sports anime, that ponders if we ever really “come of age.” When does growth end? Is it not a more cyclical process of conflagration and rebirth, of tearing down and building back up? Thinking about it this way, the restorative nostalgia that runs through the series makes sense. If we only look forward, we may grow, but we’ll lose our connection to the past. Japan will just be one giant Tokyo. If we instead revisit that history, stay connected to these collective aesthetics and the identity they project, could our growth be richer for it? Tsurune asks this of its viewers through its visual storytelling, creating a world of almost surreal beauty, yet somehow tapping into a relatable, familiar nostalgia that is nothing short of magic.

Tsurune is available to stream on Crunchyroll and HIDIVE. Tsurune: The Linking Shot is streaming on HIDIVE.