“Love and Rockets” is the last comic I bought regularly and its creators, Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez, the only comic book artists I have ever interviewed. That was 32 years ago, when the series was 8 years old, back when their publisher, Fantagraphics, was still based in Agoura Hills, between Woodland Hills, where Gilbert lived, and Oxnard, where Jaime lived and where the brothers grew up. I fell in love with their characters, with their line — Jaime’s art, especially, which even according to his brother, is what first turned heads. My irregular support in recent decades has not impacted their output — “Love and Rockets” is more of a going concern than ever — or kept the brothers from becoming even more legendary than they already were. In honor of the series’ 40th anniversary, Fantagraphics is publishing a hardbound boxed set reproducing its first 50 issues; it’s expensive and worth it.

Still, it’s highly gratifying when something that feels like one’s own cultural property gets recognition — even if people have actually been recognizing it all along — and it was a thrill to learn that Los Bros, as they’re affectionately known, have become the subject of a fine, informative documentary tribute, “Love and Rockets: The Great American Comic Book.” Directed by Omar Foglio and Jose Luis Figueroa and produced by L.A.’s KCET as part of its excellent “Artbound” series, it premiered Wednesday on KCET, airs Friday (tonight) on PBS (PBS SoCal here), and is available online. Similarly, it was a small thrill to realize (and then confirm) that, on the basis of a “Love and Rockets” T-shirt worn by Chris Estrada’s character in his Hulu comedy “This Fool,” his sometime girlfriend Maggie was named for Jaime’s comic book heroine. (There are other Hernandez homages in the series as well.)

“What is ‘Love and Rockets’ about?” asks the Times’ own Carolina Miranda, one of the film’s several commentators. “How much time do you have?”

The book is split between Jaime and Gilbert (older brother Mario was an early contributor). Their first stories had sci-fi elements (the rockets), which were soon downplayed in favor of stories about interesting ordinary people within a community (the love). Each has created his own world and expanding cast of characters; each worked outward from a small-town setting: Jaime’s Huerta (called Hoppers), with its echoes of Oxnard, and Gilbert’s wholly imagined Central American hamlet, Palomar. “I knew that would be a little bit difficult for some American readers,” Gilbert says, “but I thought if I kept at it they would get it.”

The film goes briefly into their family history — a father from Mexico and a mother from Texas who met as farm workers in Oxnard in the 1940s and had six kids — but comes around again and again to family as inspiration. “Whenever there was a family gathering it was always the matriarchs, all the women together ran things,” says Gilbert, on the brothers’ talent for writing complex, lifelike females. “There was no machismo about it, it was all laughing and cooking and playing with the kids and arguing and drinking … It was like the world.” And on portraying Latinx culture: “Even as a kid there’s great people I know, cousins, friends, aunts and uncles, adults, and they’re so colorful in an enriching, very familial way — and I go, ‘Why isn’t this represented?’”

Cover art for the “Love and Rockets” comic, by Jaime Hernandez.

(KCET)

They read comics, drew comics — Gilbert displays, with some embarrassment, his childhood “Rocket Comics” — then drew them better. Superheroes were less an influence on the brothers than were kid books and the human stories they told. Jaime walks you through some “Dennis the Menace” pages by Owen Fitzgerald. (“As a kid, I just knew this is real, these comics are home, I just can feel my mom in this, I can feel me there. And I remember going, ‘I don’t see this in a Marvel comic’”); Gilbert does the same for Bob Bolling and “Little Archie.”

Eventually, at Mario’s suggestion, they put out an issue on their own, borrowing money from another brother to print it, folding and stapling the copies themselves. They sent one off to Fantagraphics, whose “Comics Journal” they admired, hoping for a review. They got the review — along with an offer to publish the book, with additional pages, and then a request for a second issue. It went on from there.

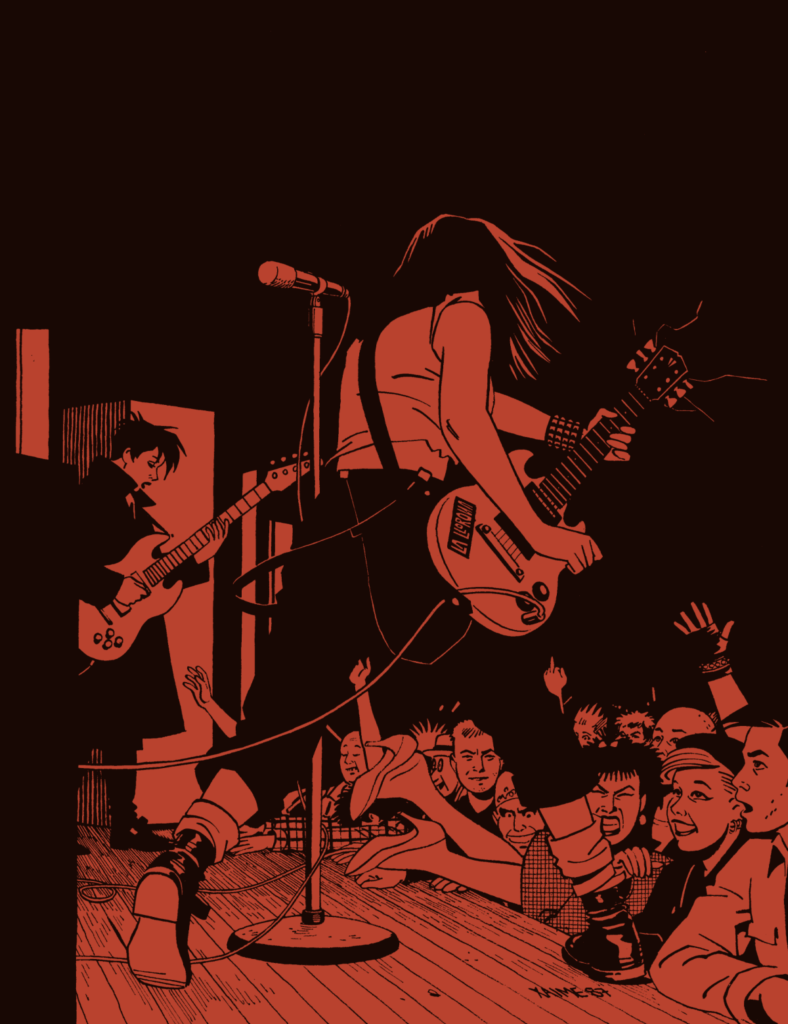

There are a lot of cultural call-outs and homages in the books, and “Love and Rockets” can also be read as the story of the artists’ own personal growth, self-education and flowering interests. When I asked about non-comic, non-punk inspirations back in 1990, Gilbert cited Fellini films, Sophia Loren, “the kids in the movie ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’” Victor Hugo, “the look and setting of the Brazilian film ‘Black Orpheus,’” and Elvis; Jaime brought up Paul Klee, Toshiro Mifune, Robert De Niro in “Raging Bull,” Rembrandt, baseball, Johnny Cash, “the young Bardot,” and professional wrestling. Early on, they fell for punk rock — in one scene here they visit Chinatown and recall the bands they saw play the Hong Kong Cafe — which influenced the independent ethic that still rules their work, as well as the way Jaime dressed his characters and the milieu he made for them. That has changed over time, as their characters have aged along with the artists. Maggie is now nearing 60.

“You can see the progression of how the characters have evolved physically over time,” says Miranda. “One of the things that makes their comic book so compelling is that these are never static people, these are people who age, they gain weight, they lose weight, they change their hair. It’s just great to feel that they evolve like real people.”

Best of all, “Love and Rockets: The Great American Comic Book” conveys the pure pleasure of seeing their art — the strips in brilliantly composed black and white, the covers in color — magnified on the screen. The film includes close-up scenes of the brothers at work, taking characters from pencil sketch to inked finished drawing with magical control. (I was going to write “ease,” but I’m sure that’s wrong.) Jaime and Gilbert have quite different styles — Jaime tending toward a classically balanced, clean-lined realism, Gilbert wilder and more cartoony. But they sync well enough that every so often they will split a panel between them.

It’s a brother thing. It’s a life’s work.