“Have you ever fallen asleep in class and woken up with a jolt?”

That’s more or less the most precise way to articulate the vibe Japanese singer and composer Eve (stylized as “E ve”) gives off in his work. For most of a decade, his animated music videos have been chasing that ephemeral feeling of a dream that feels too fantastical for reality, yet solid enough to be a memory. In his songs — featured in anime like the Jujutsu Kaisen series and the movie Josee, the Tiger and the Fish — everyone shares that uncanny feeling, where the line between dream and repressed anxieties gets blurry, represented through the clash and hybridization of music and different kinds of animation. Eve’s new audiovisual work Adam by Eve: A Live In Animation, now streaming on Netflix, is a multimedia experiment that sifts through all his work to this point. Though it’s packed with remixes of and callbacks to Eve’s history, it’s a dazzling, surprisingly accessible summation of his visual and sonic styles.

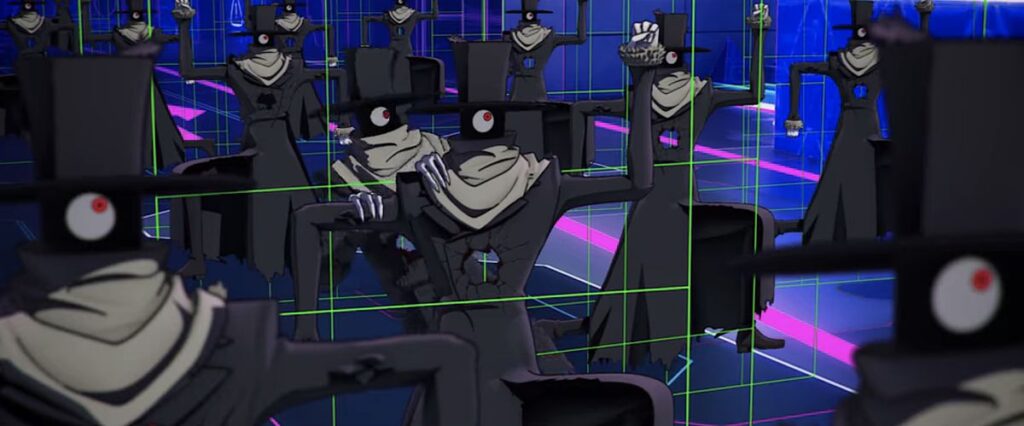

The story’s focal point is one of Eve’s past creations, “Hitotsume” (One-Eye), a supernatural being that appeared in Eve’s manga Kara no Kioku and several of his music videos. Here, One-Eye is a mysterious being that appears in people’s dreams, particularly those of high-schooler Aki (actress/model Hanon), who is searching for her missing friend Taki (singer/model Ano). It doesn’t take long for Adam by Eve to take on the general tone of the singer-composer’s music videos, that of a kind of odd waking dream. This 58-minute music video/concert film/animated dream journal pushes that idea to its logical end point, with Eve’s dreams and visual imaginings intruding into the real world, in the form of animated beasts and disembodied limbs that crawl out of billboards and drift across highways and rooftops.

Given that the work here covers most of Eve’s career, it’s appropriate that he once again calls on a handful of his closest collaborators. Chief among them: screenwriter and editor Nobutaka Yoda, who has directed many of Eve’s music videos, such as “We’re Still Underground” and “Heart Forecast.” Nobutaka’s authorial voice might be the second loudest element in Eve’s career. The film also sees Eve reteaming with Waboku, who directed the music videos for Eve’s “Okinimesumama” and “Tokyo Ghetto.” Here, he directs the animation for the segment featuring the new song “Taikutsu o Saien Shinaide.”

Produced by Studio Khara, best known for the Evangelion Rebuild quadrilogy (a series which itself has shown an interest in animation colliding with the real world), Adam by Eve feels like a revisitation for Nobutaka as well as Eve. The former’s psychedelic music video for “We’re Still Underground” supplants fantasy into the everyday, as its main character drifts through a magical land as if nothing had changed from the city he normally resides in. The clash between colors and textures, the real and the impossible, is expanded in Adam by Eve, even as other directors take over for distinctive segments.

Adam by Eve recalls the visual roughness and experimentation of indie anime rather than the blockbusters that studios such as Khara are primarily known for. For much of the first half, Nobutaka’s playfulness with editing and the texture of his imagery are upfront, superimposing animation and text over already spliced and split-screened live-action imagery. It’s frequently overwhelming, as though the artist’s imagination is bursting forth from his silhouetted image.

The mix of that playfulness with a very sincere story feels like a perfect embodiment of the relationship between Eve’s intricate, upbeat, uptempo compositions and his more melancholic lyricism. Nobutaka’s use of superimposition also makes for an interesting synchronicity with Eve’s preference to keep his face obscured during performances. So Eve becomes another surface for these animated images to be projected onto, in a curious inversion of the artist’s usual relationship with these drawn characters acting as avatars for him.

Though animation is present throughout the whole feature, there are only a few wholly animated sequences, as the story gradually builds toward the promise of its hybrid between media. The fully animated sequences are reserved for the new tracks that accompany the film. Khara animator Hibiki Yoshizaki (Evangelion: 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon A Time) directs the animation for the segment featuring Eve’s new song “Bōto” (“Mob”), a compellingly creepy vision of a world first completely subsumed by One Eye, then undone in an unleashing of repressed frustration in a mix of both 2D and 3D CG animation. Then one of Eve’s best-known songs, “Kaikai Kitan” (the opening theme of Jujutsu Kaisen) becomes the film’s denouement. As handled by visual-effects artist group Khaki and animator Yūichirō Saeki, it explodes outward in multiple media, as a triumph over the conformity and consumptiveness seen in that previous animated segment.

Image: Netflix

For some people, the words “live-action/animation hybrid” might recall Who Framed Roger Rabbit and its ilk. And “adult anime visual album” might similarly conjure up memories of Interstella 5555: The 5tory of the 5ecret 5tar 5ystem, the sci-fi companion to Daft Punk’s album Discovery, or even the more recent Netflix musical anime project Sound and Fury. But Adam by Eve doesn’t have much in common with those works — it takes a less structured approach to its visual storytelling. If anything, that early half recalls the rulebreaking work of House director Nobuhiko Obayashi in its use of collage and superimposition, with animated elements intruding into live-action frames as a symbol of the supernatural. Superficially, there’s a little bit of House in the way Adam By Eve’s animation transforms the texture of its live-action imagery into something more ethereal.

The project does follow some rules, however — cleverly, the film divides the live-action and animation between songs old and new — so tracks like “Heart Forecast” that already have animated music videos are recontextualised within this story. “Heart Forecast” specifically spells out Aki’s longing for her friend as it plays over scenery of her memories of frivolous pastimes. As a reminder of the song’s changed significance, its music video plays on a screen in the background.

Admittedly, the meanings of Adam by Eve still remain a little opaque on first viewing. At points, the monster One-Eye represents commercialism and conformity and perhaps even patriarchy. At other times, he seems to represent more acute concepts, like anxiety and romantic longing. There’s a surprising amount to unpack here, and it’s probably easy to miss some symbolism in terms of the frames of reference and the artist’s backgrounds, things that feel like they might be rewarded on a rewatch, given the film’s barrage of imagery. But simply looking at its fluid, fascinating collision of dreams with reality, it’s a satisfyingly bold adult animation project, one interested less in clear narrative, and more in visual expression for its own sake. In any case it all feels very distinctly Eve, like a projection of the singer’s mind directly into our world.

Adam By Eve is streaming on Netflix now.