When people think of Ray Romano, they invariably start with “Everybody Loves Raymond.” Since that series ended in 2005, though Romano, 65, has steadily chosen darker and more dramatic projects: He co-created the drama “Men of a Certain Age” and has appeared in a raft of dramedies such as “Parenthood,” “The Big Sick” and “Made for Love.” He even played a mob lawyer in “The Irishman.”

Now Romano’s ambitions have taken him into new territory yet again — he has co-written (with “Men of a Certain Age” partner Mark Stegemann) and directed a feature film for the first time.

“Somewhere in Queens” is a dramedy about a working-class Italian American family starring Romano as Leo, a well-intentioned schlub who works in construction with his brother and father, though they constantly remind him of his shortcomings. Leo is hoping his son Sticks (Jacob Ward), a quiet and anxious boy who is also a high school basketball star, has a future beyond the narrow misery of the family business. To guide Sticks in the right direction, Leo makes some (foolish and increasingly ill-advised) moves.

The film also stars Laurie Metcalf as Leo’s tightly wound wife, Angela, as well as a collection of actors who are either New York-born, hail from the comedy world or both, including Tony Lo Bianco, Jon Manfrellotti and Sebastian Maniscalco.

Romano recently joined The Times via video conference to discuss the film. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Where did the idea come from?

Ray Romano: Elements of the plot came from my life. I knew I wanted to write about the working-class Italian American world that I grew up in and married into even more — my wife is from Sicily and her parents came over when they were 40.

At the time my son was graduating high school and was a star basketball player. He wasn’t going to play in college and at his last game I had tears in my eyes — I was going to miss going to his games. But if I was being truthful I realized — and this was selfish — I was also going to miss being the father of the star basketball player. It was fun.

So you put that story into the working-class world, where this poor guy has nothing else and lives vicariously through his son and feels important when he’s in the gym.

Then I added the wife, who is an overprotective Italian American mother who is a breast cancer survivor — my wife is a breast cancer survivor. And my kid, like Sticks, has suffered from anxiety and social anxiety. So I put all those elements in.

Were you looking to direct?

I always wondered who we would get to direct and then my agent said, “Why don’t you direct it?”

I said, “No way, that’s the stupidest thing you’ve ever said.”

He kept trying to persuade me, asking why I’d give this very personal story to someone else. I said, “Because someone else knows how to direct a movie.”

I knew what I wanted the film to look like, but I was not familiar with anything behind the camera. I didn’t know about the technical side, about lenses and lights. My agent pointed out that Chris Rock doesn’t know about that either and just gets a good cinematographer and then worries about the story and the performances.

It was hard to say OK, but I reluctantly agreed with him and jumped off the cliff. As nerve-racking as it was, once we started, the nerves went away and I became consumed with the work.

Romano, right, with Brad Garrett in “Everybody Loves Raymond.”

(Michael Yarish / CBS)

Did you like it enough to do it again?

Not for a script that I didn’t write — I’ve gotten a few offers but they’re not stories I’m passionate about and have a vision for. But we’re trying to write another script and I’d direct that.

Tonally and thematically this reminded me a bit of “Men of a Certain Age” — Leo’s father in this movie is similar to Andre Braugher’s father in that show.

I’m a child of that father. My father, who had a rough childhood — his father left when he was 2 years old — had a very hard time expressing emotion and being demonstrative. It molded who I am.

I try not to be that father personally, but when you grow up that way, behaving differently is not easy. I’m much better with my kids than my father was, but it doesn’t come as naturally to me as it does to my wife.

It’s writing what you know, but it’s also something a lot of people experience. Still, I don’t think I can do it again in my next script — I’ll have to have a functional father.

Did the show and now the movie make you look back at your own parenting mistakes with more acute regret or more forgiveness?

You’re assuming that I’ve made mistakes.

I wish I was not that guy who feels uncomfortable expressing their emotions to their children and being able to have those open talks. I wasn’t so bad that I regret what I’ve done, it’s just that I could have done better.

As a person who experiences anxiety himself, I was able to recognize it in my son and I was able to talk to him about that and relate to him on that level. My wife, luckily, hasn’t experienced that, so it’s something I have to explain to her.

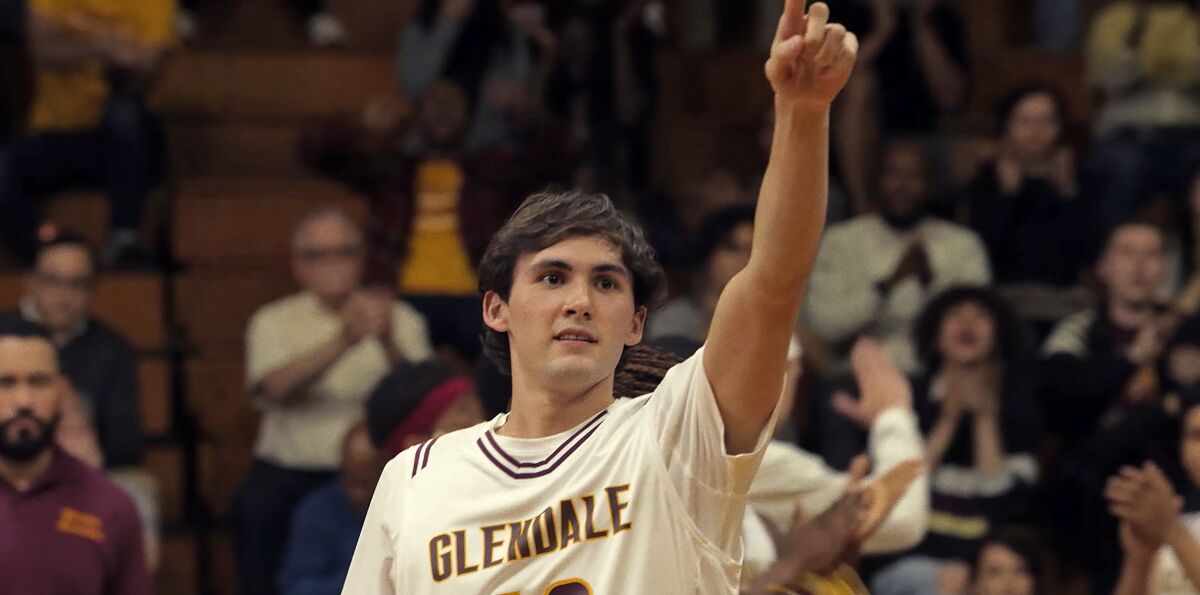

Jacob Ward plays high school basketball star Sticks in “Somewhere in Queens.”

(Mary Cybulski / Roadside Attractions)

The film opens with a very New York, very Italian American wedding scene capturing people in intimate moments and offering frank video testimony. Was that part of the plan from the beginning?

We wrote it as a long one-shot, with the camera capturing a little piece of every table — the aunt screaming about the baby and the girl arguing with her boyfriend for looking at the bridesmaids — and we filmed it. But it never really worked and so we decided to add video camera testimonials. We wrote them on the spot. One of the first women says, “I never seal the envelope until I see how good the party is. It’s all in here!” We gave it to an extra, to a woman who just looked the part. She nailed it.

Then we cobbled it all together in the editing. I’m learning that directing doesn’t all go as planned, so get stuff on camera.

Were you concerned that you were making too New York a movie or did you feel the specificity actually made it universal?

[“Everybody Loves Raymond” creator] Phil Rosenthal said, “You never try to write to please or relate to everybody, because then you will relate to nobody. Make it specific.”

I wanted it to appeal to everybody, but I wrote it to be specific. It’s ultimately about family — yes, they’re Italian American and have dinner at noon and eat cannolis and sing “C’é la Luna” — but it’s relatable. It’s filtered through this one family, but the core of it is people trying to deal with their anxiety or get validation from their father.