It’s the noble job of science educators to bring the distant cosmos down to Earth, where it can ignite human fascination in more than an abstract way. But the total solar eclipse that will cast its shadow across thousands of miles of North America this Monday doesn’t need any help. Along the path of totality temperatures will drop, wildlife could become confused, and it may get dark enough to see other planets, in a kind of 360-degree sunset.

Which is why there’s no better time to watch Sunshine, the cerebral sci-fi thriller written by Alex Garland (Ex Machina) and directed by Danny Boyle (28 Days Later). Whether you’re in the path of totality or not, you can bring the expansive awe and crushing terror of the cosmos into your living room with a film that discards the factual reality of space exploration in order to get the visceral reality just right.

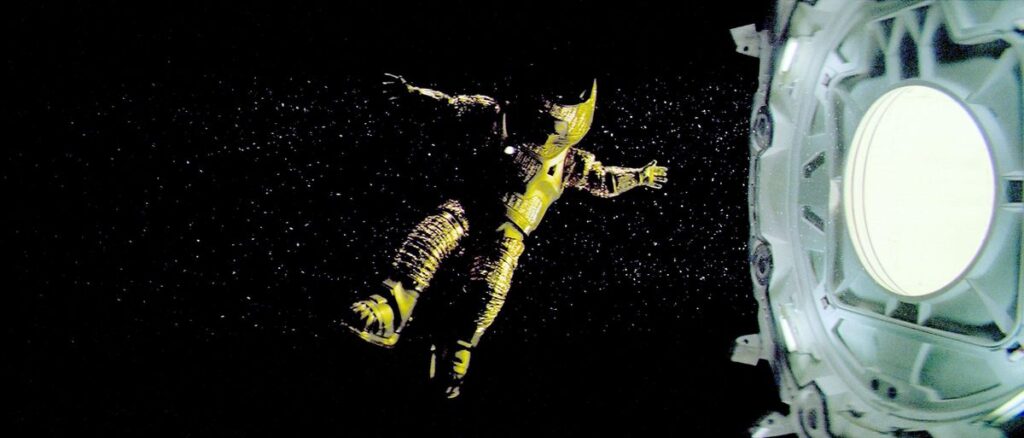

Plot-wise, Sunshine can be described variously as if it were a dumb action movie (the sun is dying, and a team of experts must save the world by driving a nuclear bomb into it), a psychological art film (long-haul astronauts are slowly driven to various degrees of madness by the sheer enormity of the idea of approaching the sun), and a white-knuckled horror flick (there’s one more person on this spaceship than there’s supposed to be), all with relative accuracy.

Cast-wise, Sunshine functions as a very specific snapshot of Hollywood in 2007, before a shocking number of its actors — Cillian Murphy, Chris Evans, Rose Byrne, Michelle Yeoh, and Benedict Wong — had become blockbuster names. Protostars, if you will.

Garland and Boyle assembled that international cast to reflect a half-century of growth in Asia’s spaceflight programs, assigned them to live together as their characters would, took them on trips to tour the cramped quarters of a nuclear submarine and for a ride in NASA’s “vomit comet” to experience weightlessness, and suggested reading on the experiences and psychology of astronauts. They hired science advisors and futurists to consult, and even a professor to lecture the cast on solar physics.

But don’t mistake Sunshine for The Right Stuff or Apollo 13. This is not your typical scientifically dedicated space exploration flick, and the elements of unrealism are everywhere. For one thing: The sun will not die in the next 50 years, and even if it did, there aren’t enough nuclear raw materials in the entirety of the Earth to reignite it with a bomb. The movie’s ship, the Icarus II, has artificial gravity, and it makes sound as it sweeps through space toward its fiery end point. And yet…

Image: Fox Searchlight/Everett Collection

Sunshine is beloved by many hard science fiction fans — including some real scientific accuracy sticklers that I know — because of its commitment to the emotional fidelity of real space exploration. Even some contemporary reviewers who knocked it for its inaccuracies admitted: In the psychology of space exploration, Sunshine shines. Boyle shoots the movie with a frankly stressful dedication to claustrophobia, and while Garland’s script somewhat begrudgingly makes room for some summer blockbuster-style romance and action, the real oomph of the thing is characters simply grappling with space itself.

The movie repeatedly feints toward the supernatural, but never goes fully over the event horizon into science fantasy, and it doesn’t need to. The vast, lonely reaches of space and the gravity well of the sun render that line blurry enough on their own. Woven through the crew’s hardships is an inescapable sense of profundity that’s only enhanced by their mortal reality: Living day by day with a mere hand’s span of metal, not miles of gravity-trapped atmosphere, separating them from raw cosmos.

Their struggles are as real as the laws of physics, and profound and ineffable as any religious experience, and you can say that about a solar eclipse, too. When the sky goes dark, the birds get quiet, the wind drops, the air gets cold, the sun goes black, and the people who look upon it are struck blind, what else can you call it but biblical?

Sunshine might leave you with more questions than answers, but that’s a part of the eclipse experience, too. This week, the moon and the sun will bring the cosmos down to Earth for us in one of the most visceral ways it can — just as Boyle and Garland showed that sometimes emotional accuracy reaches further than the technical kind.