When the first trailer for Lucasfilm’s latest Star Wars series, The Acolyte, dropped back in March, the group email for my Star Wars: Edge of the Empire role-playing game immediately blew up. The tongue-in-cheek question on our minds was whether someone at Lucasfilm had been secretly monitoring our latest story arc: Our game is set during the Old Republic era and The Acolyte is a High Republic-era story, but otherwise, everything we knew about the new series seemed entirely compatible with the original story our game master had whipped up, about a Jedi kidnapping dozens of Force-sensitive children for training, and quietly advising the local Commerce Guild outpost on ways to violently suppress the local uprising that resulted.

From what we knew about The Acolyte back then, it just seemed like a funny coincidence that the show’s teaser and the arc we were about to conclude were so in sync. We assumed once the series aired and its storyline was clearer, it’d be a lot more obvious that the Jedi were meant to be the heroes in The Acolyte, and any seeming morally gray areas would be cleared up.

But episode 3 of The Acolyte doesn’t make anything clearer. If anything, it muddies the already pretty murky waters around the ways the Jedi acquire kids for training, and how they treat those kids once they have them. The episode deliberately obfuscates a lot of important detail about what happened on the planet Brendok, clearly with some form of reveal to come, possibly even exonerating the Jedi from, for instance, murdering everyone in Mae and Osha’s witch coven. But what it does show us about Jedi recruitment tactics sure doesn’t paint them in a positive light.

[Ed. note: Spoilers ahead for The Acolyte season 1, episode 3.]

Source images: Respawn Entertainment/Electronic Arts

Consider the events of this episode in the most generous light possible, from the presumed Jedi perspective. At this point in the Star Wars timeline, they’re a significant power in the galaxy, essentially space cops out to protect the Republic, prevent the balance of the Force from shifting toward darkness, and prevent war from spreading across the galaxy. They find a forbidden cult creating and training children, all while lying to the authorities and claiming they aren’t doing any of that.

Galactic law might allow the Jedi to carve a path through these criminal sect members and take the children into custody, but instead, they simply note that they’d like to know whether Mae and Osha are fit for Jedi training and interested in joining up. Osha is, so they invite her to join them. Mae then goes ham, somehow kills everyone else present by setting a stone mountain on fire, then dies in the aftermath. Fortunately, the noble Jedi are there to give the poor surviving orphan girl a home.

A strong pro-Jedi viewer stance — looking at the situation from a certain point of view, as it were — makes that read at least possible, if not entirely plausible. But the same story looks radically different from the victims’ perspective, which seems to be what the episode is taking as text. It’s entirely unclear why this Force-using coven was banned and ordered not to train children. There’s never any sense that they’re doing any harm. Their coven seems like a warm, supportive place to grow up. Their only questionable act is impressing their values and training on Osha, who’s dubious about whether this is the future she wants. But the fact that their induction ritual clearly requires her consent — and the fact that they’ve obviously educated her about the Jedi in a neutral enough way that she was allowed to decide for herself that they’re heroes — are both votes in their favor.

Source image: Pixar Animation Studios

And then these outsiders come along and stalk the children without notifying their mother or other guardians. They confront the coven in the middle of a sacred ritual. They force the children to take a Jedi suitability test without allowing their mother to be present, or telling her anything about what’s involved. (And at least half of it appears to be a medical test for midi-chlorian levels, administered without warning or consent.) After the test, they invite a minor child to join their sect, again without conferring with her mother. Whatever happens next isn’t necessarily their fault, but it unquestionably happens because they invade a seemingly peaceful, obscure separatist group and try to talk one of their children into permanently abandoning her family and coming away with them to a distant planet, where they plan to inculcate her with their own values, including a belief that emotional connections of any kind are inherently bad and forbidden.

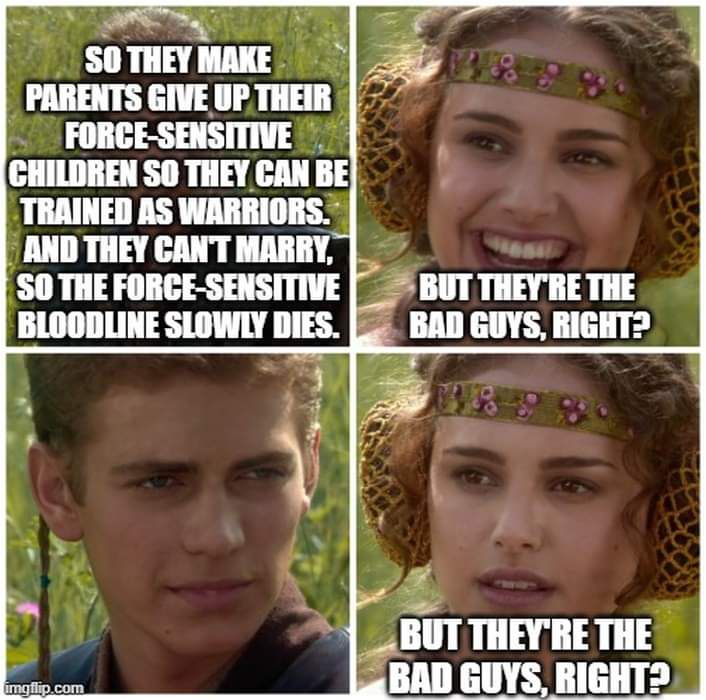

None of this is a good look for the Jedi. The whole sequence, with its deliberate omissions and obfuscations, feeds directly into the questions fans have had about Jedi recruitment since the prequel movies started showing us more about the induction process. The baseline Jedi rules are remarkably similar to real-world cult tactics: Trainees are separated from their families and taught to disavow any personal connections, they’re forced to accept their teachers’ proscriptive ascetic values, and it’s made clear that any deviation or pushback against them is cause for expulsion from their replacement family. The Phantom Menace-era Jedi also refuse trainees as “too old” starting at least at age 9, which reads as a feeling that inductees should be young enough to be malleable, without any pesky emotional attachments or opinions of their own.

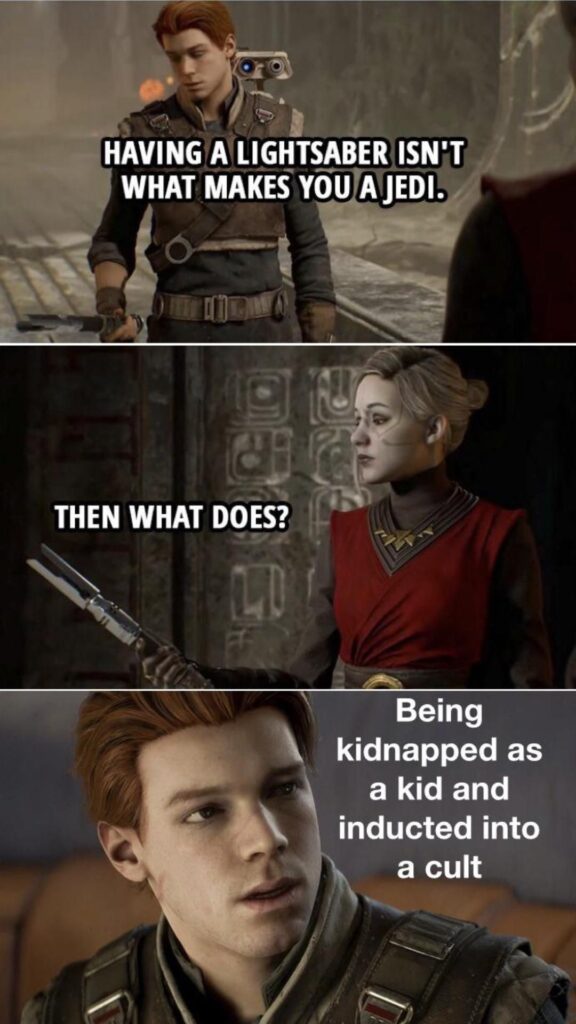

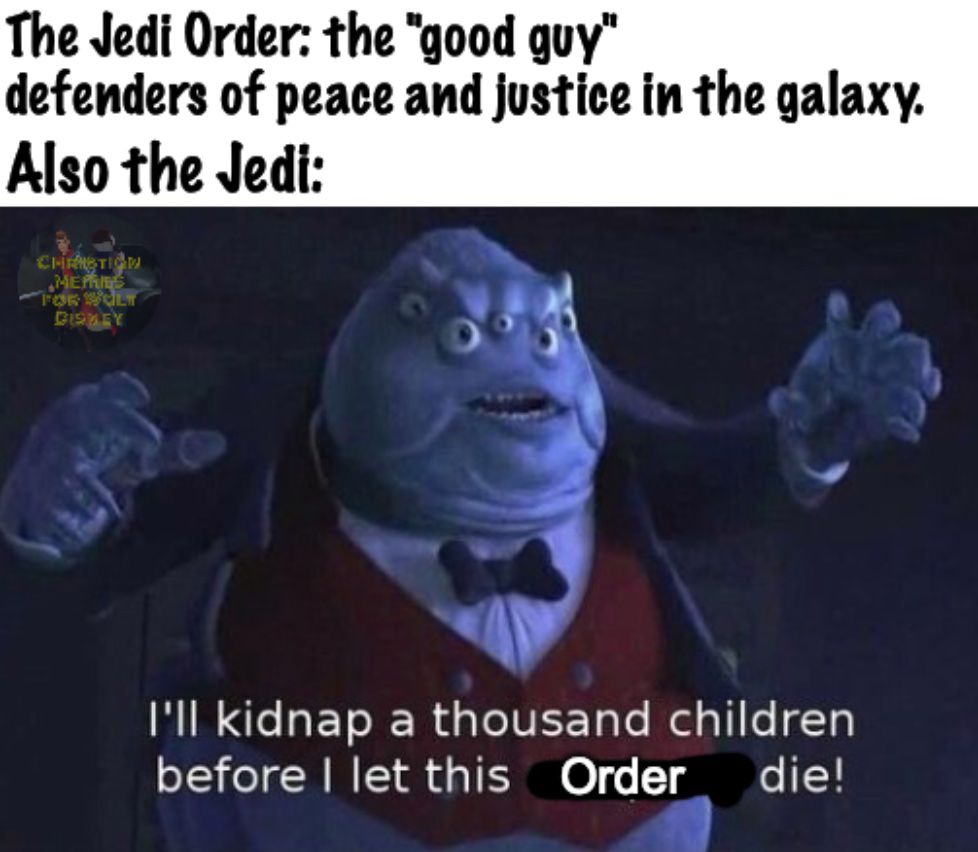

Add all that to the Jedi tendency toward doctrinaire thinking and arrogance, and you have a recipe for the entirely plausible situation we were navigating in my Edge of the Empire game, where a single Jedi decided it was so important that Force-sensitive younglings receive “proper” training that she engineered false-flag medical programs in order to get her hands on local children, test them, and then take them from their parents by force. Given some of the arrogance we’ve already seen from Jedi in the Star Wars movie and TV canon, an overreaching Jedi driven by self-righteousness seemed like an entirely plausible villain. Which is why, when that first Acolyte trailer dropped, my gaming group started trading internet memes that tapped into the same uncomfortable response to Jedi behavior around children and indoctrination.

Source images: Lucasfilm

We’ve already seen quite a bit of the same arrogance in The Acolyte, particularly in Vernestra Rwoh heavily implying that Osha needed to be rounded up quickly and sentenced quickly for Indara’s murder, as a show of Jedi strength — even if there was no evidence that Osha was guilty. Even if no one bothered with the barest baseline of investigation — for instance, checking the flight logs on the ship she was working on, to see whether she plausibly could have been in a different part of the galaxy an unknown number of parsecs away in order to kill Indara. That same arrogance leads the Jedi to drop a supposedly superpowered, Jedi-killing Force user on a droid-operated prison ship, with no guards or oversight.

And it leads Indara and her team to handle the Brendok operation in either the clumsiest, most intrusive way possible, or the most purposefully disruptive. Episode 3 deliberately hides information from the audience to make it unclear which is true — but there’s still no way to read these events so the Jedi are diplomatic, tactful, or blameless when things go wrong.

The upside of all of this, at least for Star Wars fans, is that Jedi can be terrific antagonists for a Star Wars RPG without any need for GMs to twist the canon, or for players to embrace the dark side of the Force. Arrogant agents of a Galactic organization that outlaws any organizations that disagree with its dogma, then punishes them for their beliefs by taking their children away for re-education, are already neatly set up to be villains.

All the grotesque questions The Phantom Menace raised come up again in the light of The Acolyte’s story. Why, after a Jedi lured Anakin Skywalker away from his planet and his enslaved mother, was the Jedi Council so willing to disavow the kid? When Qui-Gon insisted on training him anyway, why did he refuse to even consider the trivial effort needed to rescue Anakin’s mother, guaranteeing the kid would never be able to stop worrying about her and let go of his attachment? Why make it so clear that Anakin was only valuable as a Force-powered asset, and that his mother’s freedom, dignity, and life were beneath Jedi notice?

Image: Lucasfilm

Indara and her crew in The Acolyte are just as cold about Mae and Osha. If the coven’s beliefs or behaviors are somehow harmful and dangerous in a way we never see, the Jedi should be trying to rescue the girls, regardless of whether they test as valuable assets. If the coven isn’t dangerous or harmful, the Jedi have no business stealing their children, or circumnavigating the coven to lure their kids into a potentially permanent career path that will start with isolation and indoctrination. And the testing being mandatory and the coven being illegal both suggest that if Mae and Osha test as potentially useful to the Jedi, they aren’t going to be permitted to choose to stay on Brendok.

It’s still possible (though given Star Wars franchise history, I doubt it) that The Acolyte is embracing fans’ discomfort with the Jedi’s questionable, distasteful, and even predatory way of handling children, and exploring it with an eye toward clearing up some of the questions. We won’t find out for sure until we get to the parts of the story this episode deliberately obscures.

Until then, fans have their own ways of exploring these dubious aspects of the franchise. My RPG group resolved our own immediate crisis just before The Acolyte premiered, by aiding our own local Jedi in brokering a local peace, fighting the out-of-control Commerce Guild forces to a standstill, and helping resolve the imbalance in the Force that her hubris had caused. But that leaves us at the start of a new arc, where dozens of children are scattered throughout the Jedi training system, isolated from each other and their families, and undergoing “training” they didn’t necessarily sign up for.

To me, at least, that situation feels like an entirely fair reflection of what the official canon has said about the Jedi and their youngling inductees. Within Star Wars canon, it feels like a given that the Jedi are always the heroes, and anyone who resists them is acting out of stupidity, greed, or outright evil. But the way they deal with children has always felt potentially villainous. We’ll see soon enough whether The Acolyte’s creative team agrees, or are just teasing us with a little more fuel for a long-standing debate, while planning to gloss over the whole issue and move on without answering any of the questions it leaves standing open.