“Maestro” is the second collaboration between cinematographer Matthew Libatique and director Bradley Cooper. Libatique was Oscar nominated for their “A Star Is Born.”

(Netflix)

During the awards-season campaign for “A Star Is Born,” the 2018 remake that he shot for first-time feature filmmaker Bradley Cooper, Matthew Libatique began hearing about the project that would become “Maestro.”

“He loved talking about it,” the cinematographer says of Cooper. “We started talking about lensing right away, theorizing about the format and the aspect ratio.”

Cooper was speaking Libatique’s language: The decorated director of photography, who has been twice nominated for the Oscar, including for “A Star Is Born,” was excited to dive into how to visually tell the story of Leonard Bernstein. But he was surprised where Cooper’s interest in the material would eventually take him. “I assumed there’d be more about Leonard Bernstein the conductor-composer, but it was really Leonard Bernstein the married man. It became about Felicia as much as it was about Lenny.”

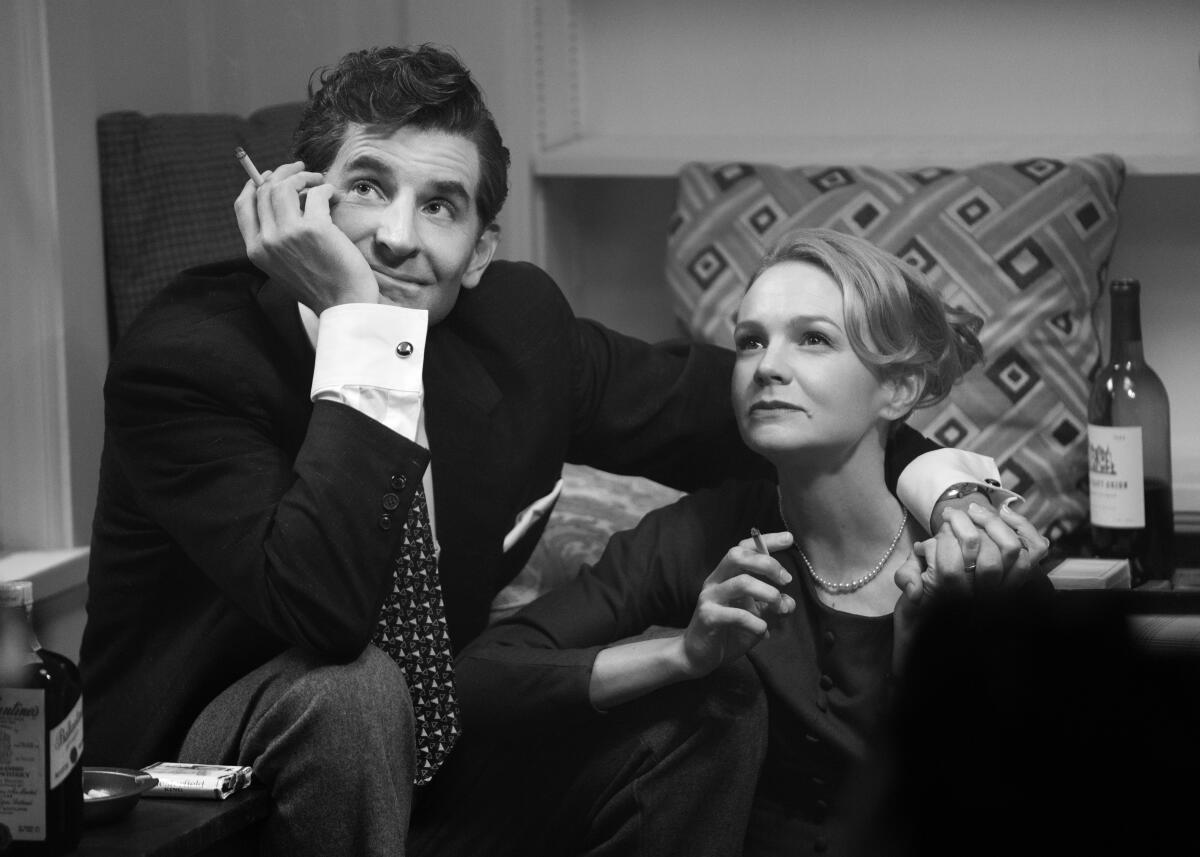

Indeed, “Maestro” is a moving portrait of the imperfect marriage between Bernstein — played by Cooper — and his wife, actress Felicia Montealegre, brought to luminous life by Carey Mulligan. Shot on film in different aspect ratios — sometimes in black and white, sometimes in color — the movie is widely considered a more audacious and confident work by Cooper, but Libatique found the actor to already be fully formed as a director when they met to discuss collaborating on “A Star Is Born.”

Bradley Cooper and Carey Mulligan in the movie “Maestro.”

(Jason McDonald / Netflix)

“I wasn’t teaching him anything,” Libatique recalls. “I never considered him a first-time director. He’s an editor, basically — he edits in his head, and he spent a lot of time in editing rooms with some great filmmakers: David O. Russell, Guillermo del Toro, Clint Eastwood. He understands shots and maximizing performance.”

Bernstein and Montealegre’s electric courtship is presented in the classic Hollywood aspect ratio of 4:3 in black and white, eventually shifting to color once the story jumps forward in time, the couple’s marriage now at an impasse. Libatique was struck by Cooper’s instincts for how to capture those shifting emotions, especially during a pivotal moment when the couple argue in their Manhattan apartment as the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade travels past the window behind them. The stationary camera is placed at a distance, silently observing the characters’ fragile connection painfully unraveling because of Bernstein’s infidelity.

“We did three takes of that scene,” Libatique says. “The first one, Felicia was sitting down in a chair and Lenny sat down on the little chaise. The second take, she gets up and goes to the window. Third take, she stays in the window.” The discomforting intimacy of the sequence has stayed with him. “Bradley has said it’s like when he was small and his parents would fight — he would watch it from afar, not up close.”

During a pivotal moment in their later years when the couple argue in their Manhattan apartment, cinematographer Matthew Libatique placed a stationary camera at a distance, to give the actors the space they needed.

(Courtesy of Netflix)

“Maestro” features virtuoso set pieces — including an early sequence in which a young Bernstein gets his big break conducting the New York Philharmonic, the camera following him as he dashes from his apartment to the stage — but some of the most affecting are the stillest, such as later when Montealegre’s terminal cancer takes hold. For Libatique, that heartbreaking sequence, although hardly flashy, presents a unique test for a cinematographer.

“It’s more about what I take away,” he suggests. “I just try to keep it as simple as possible. I work hard to strip the scene [down] so the actors have a peripheral vision that’s not obstructed — just keeping it really quiet and then allowing the director to do his work and the performer to really excel.”

Libatique hasn’t worked on black and white film in a long time, harking to one of his first features, 1998’s “Pi,” which he shot with frequent directing partner Darren Aronofsky, whom he met when they were students at AFI. “It was like going way back [to] the very beginnings of my career,” Libatique says. “I was lighting a different way, and I was relearning things. It was a challenge, but what I really gravitated towards is the challenge.”

Not that the relearning process necessarily made him nostalgic for his early DP days before the prevalence of digital filmmaking. “I think what I enjoyed most is that I know what I know now. When I was young, if I saw a problem, I didn’t really know what it was — now I do. But it felt good to shoot film stock — there was a light meter and an aperture setting and an understanding of the film stock I was shooting. It doesn’t get better than that from the purity of cinematography.”

It’s now been 25 years since “Pi,” Libatique’s career highlighted by multiple collaborations with prominent filmmakers like Aronofsky, Jon Favreau, Spike Lee and the late Joel Schumacher. You can now add Cooper to that list, the bond first formed on “A Star Is Born.” “I operated [the camera] a lot on ‘A Star Is Born,’ a lot of the handheld performance stuff,” he says, “and we really connected there. He’s so passionate [about] the camera — he was like, ‘That’s where the movie’s being made.’ He knows how to filter everything inside of that frame to make it a reality for him.”

Libatique exudes a noticeable pride when he mentions these long creative partnerships. Much like the love affairs in “A Star Is Born” and “Maestro,” it’s a delicate relationship that needs to be cared for. But the rewards are endless.

“I do enjoy working with the same people, because it becomes a very intimate thing making a film with somebody,” he says. “Especially when you love the project and you love what the film’s meaning to people, that carries over into a working relationship — and a friendship in many cases. I feel very privileged.”