It’s hard to describe just how famous and revered Joe DiMaggio was during his lifetime. If you combined the admiration and respect society has for Derek Jeter, Wayne Gretzky, Arnold Palmer, and Lionel Messi, you might be in the same ballpark as what the world felt for Joe DiMaggio. DiMaggio is still worshiped by baseball fanatics and historians some 17 years after his death. He is easily one of the best baseball players who will ever play the game. His 56-game hitting streak is considered by most to be nothing short of magical and very likely unbreakable. He was a 13-time All Star, a 9-time World Series champion and a member of the Hall of Fame’s All-Century team. With those accolades, you might be surprised to know that very late into his life, Joe was surprisingly NOT rich. He lived in a shabby rented apartment and compulsively sought out free meals and gifts. That all changed thanks to a chance meeting with an extremely smart lawyer who helped Joe earn an enormous fortune by the time he died…

During his 13 season career, Joe DiMaggio earned a total of $632,250 playing professional baseball. After adjusting for inflation, that’s the same as around $8 million today. His highest salary per year was $100,000, which he earned in both 1949 and 1950. That’s the same as earning around $1 million per year today.

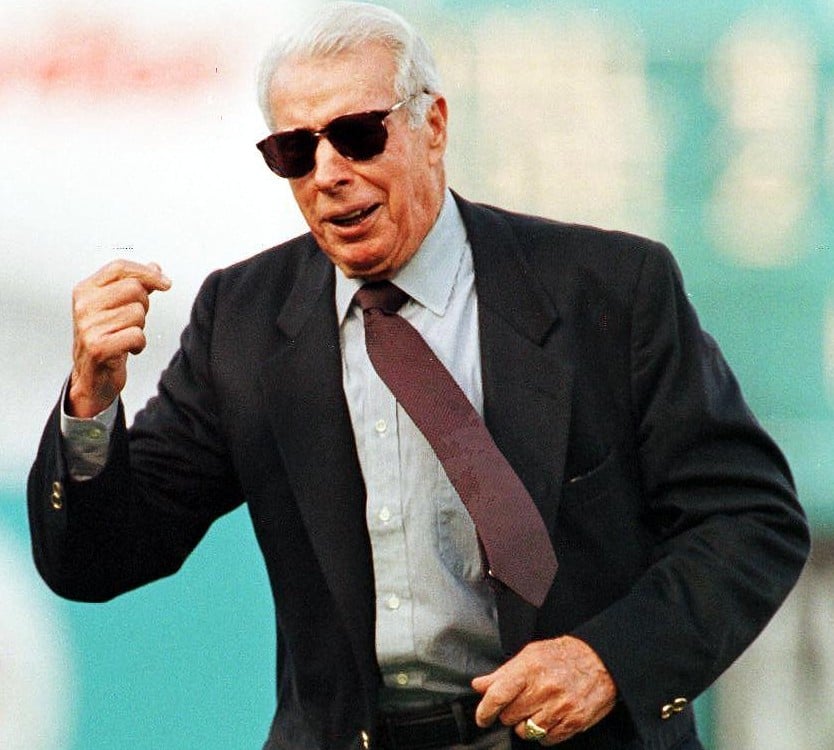

Getty Images

Yet despite these riches, after several failed marriages and bad business management, by 1983 the 68-year-old Hall-of-Famer was only worth around $200,000. That’s the same as around $450,000 today. Joe lived in a cheap Florida apartment and drove a modest Toyota that was given to him by a local dealership. He lived carefully on a $10,000 per year budget, roughly $24,000 today. He was so afraid of spending money that he rarely used his air conditioner, wore clothes that were given as gifts and rarely ate out. When he did eat at a restaurant, someone else was picking up the tab and Joe would always bring home a doggie bag with the table’s leftovers, including the restaurant bread and butter.

AFP/AFP/Getty Images

1983 was also the year that Joe’s finances would change dramatically for the better, and it was all thanks to a chance encounter with a lawyer named Morris Engelberg.

Friends arranged for Joe to have brunch with Engelberg, who handled money for very wealthy clients in Palm Beach, including members of the Getty family. During this meeting, Joe mentioned that he suspected Bowery bank was planning to cut his endorsement salary. Upon hearing this, Morris offered to act as his agent to see what was going on and if he could help. Engleberg ended up not only preventing Bowery from cutting Joe’s salary, but he actually got them to give him a big raise.

Joe was delighted and hired Morris on the spot to be his personal business manager. It was the birth of a fruitful relationship that would last for the remainder of Joe’s life.

Recharging Joe’s Finances

Morris immediately poured himself into DiMaggio’s finances. He was shocked to learn that one of the most famous people in America was only worth $200,000. He learned that, prior to their introduction, Joe’s main source of annual income was performing a handful of autograph signing events that typically paid $10,000 per session. Morris immediately raised the fee to $25,000. Then $50,000. Then $75,000. He eventually made it so anyone who wanted to hire Joe for an autograph session had to pay a guaranteed minimum of $150,000 and be willing to pay much more if Joe ended up signing a certain number of pieces.

At one signing session at Hofstra University, Joe signed 2000 pieces and earned $350,000. That’s the equivalent of $830,000 for roughly three hours of work.

One of the biggest deals Morris scored was with a memorabilia company called Score Board. In return for Joe’s signing of 1,000 baseballs and 1,000 photographs per month for two years – work that took two days per month to complete – Score Board paid Joe $9 million over those two years. That’s the same as $20 million today for 48 days of work, and the equivalent of making $416,666 per working day.

RHONA WISE/AFP/Getty Images

Morris also arranged for Joe to receive significant pay raises for his traditional endorsements with companies like Mr. Coffee, and set his personal appearance fee to show up at an event (and not sign autographs) at $50,000.

It was an unusual relationship to many of of Joe’s family members. Joe couldn’t have been happier, but Morris seemed to have an almost Svengali-like control over his client. And it was even weirder because at no point during their 16-year working relationship did Morris take a fee beyond a very modest retainer he accepted every year to keep their transactions professional. By declining the standard 10% manager’s fee, Morris essentially threw millions upon millions of dollars away.

Why was Morris OK with this arrangement? Because he was obsessed with being friends with Joe and making him happy. (It also didn’t hurt that Morris ended up with millions of dollars worth of extremely rare DiMaggio memorabilia that he did eventually sell at auction.) It got to the point where the two ended up buying mansions across the street from each other in an exclusive Florida gated community. Actually, Morris bought a mansion. Joe was given his mansion free of cost in return for being the spokesman of the community and playing golf with VIPs three times a week.

It was a very mutually beneficial relationship right up until the slugger’s death in 1999, at the age of 84.

Joe DiMaggio’s Net Worth At Death

Remember, back in 1983, Joe’s total net worth was $200,000, roughly $450,000 in today’s dollars. Thanks largely to Morris Engelberg, at the time of his death in 1999, Joe’s estate was valued at a minimum of $40 million. It could also have been as high as $80 million. That’s the same as $60 – $120 million in today’s inflation adjusted dollars.

Joe’s will spread his wealth largely to family members which included a nephew and some grandchildren. These same family members also ended up with tens of millions of dollars worth of DiMaggio memorabilia that they subsequently sold at auction.

A fairly impressive outcome for a guy who was the son of Italian immigrants who were so poor during the Great Depression that they forced all nine of their children to get jobs instead of go to high school!