William Klein won his place in photographic history in 1956 when he published his first book, Life Is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels. Shot on the streets in his native city in 1954, and edited and designed by Klein, it was a high-octane vision that included deliberately blurred, distorted, and overexposed photographs plus a panoply of effects such as crops, bleeds, found ephemera, found typography, and tart captions stating “New York is a monument to the $. The $ is responsible for everything, good and bad, and it is the best thing the city has to offer.”

“My aesthetic was the New York Daily News,” wrote the photographer, who has died aged 96. “I saw the book I wanted to do as a tabloid gone berserk, gross, grainy, over-inked, with a brutal layout, bull-horn headlines. This is what New York deserved and would get.”

Klein, who was born in New York in 1926, tried to publish his photographs in the US but was knocked back; the editors he showed his work to responded, “This isn’t photography”, “This is shit”, and “This is not New York, too black, too one-sided, this is a slum”, he later said. But informed by the existentialism of postwar France, where he had lived on and off since 1947, his book found a home at Éditions du Seuil in Paris and became an immediate success, winning the Prix Nadar in 1957.

It was also published in full in London and Rome and, striking a chord with the beat generation back in the US, quickly spread among photographers there. From 1957 it was distributed in Japan and, combined with Klein’s own visits in the early 1960s, went on to inspire a whole new generation of image-makers, broaching Japan’s socio-political situation in a radically inventive style. The latter influence was acknowledged at London’s Tate Modern in 2012, in the exhibition William Klein + Daido Moriyama.

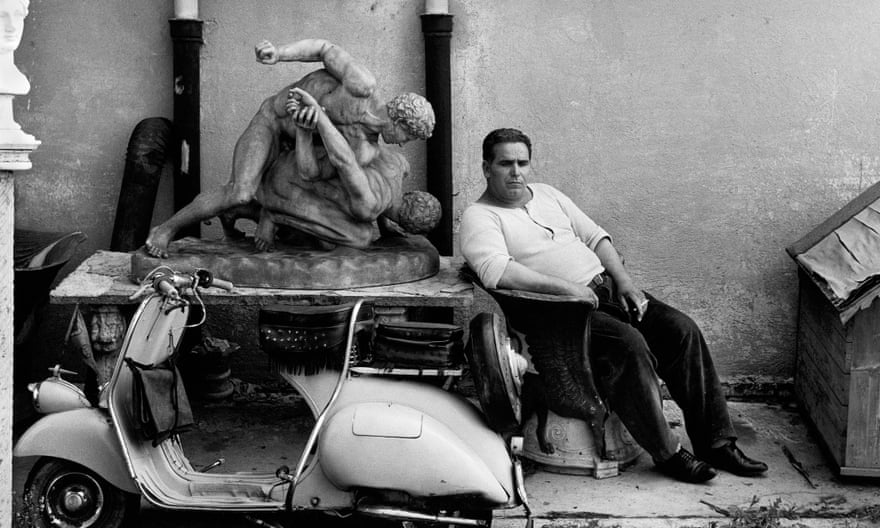

Klein went on to publish numerous other photobooks, including Rome: The City and its People (1959), Tokyo (1964), and Moscow (1964), and helped revolutionise fashion photography along the way with his work for American Vogue, taking models out of the studio and into the streets. But he soon moved into moving images, making a short titled Broadway by Light in 1958 that was hailed by Orson Welles and later recognised as a pop art forerunner. Klein went on a more political trajectory, making documentaries about France’s May 68 protests, Muhammad Ali, the first pan-African festival of Algiers, and Black Panther activist Eldridge Cleaver (among others), and co-directing an indictment of the US invasion of Vietnam with image-makers such as Jean-Luc Godard, Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnès Varda. He later described this work as “a mid-life crisis of politics” but it seems newly relevant now.

The same can be said of Klein’s feature films, which satirised the time in which he lived but also pick out still-recognisable elements of western society. Qui Êtes-Vous, Polly Maggoo? (1966) is a critical look at the fashion and media industry, while Mr Freedom (1969) is an anti-American comic-book caricature, which was censored for nine months by the French government. “Frustrated by the limited audience a documentary reaches, I thought a cartoon and circus film more accessible,” he stated. “Also more in keeping with our comic-strip politicians and ideology.”

From 1975-76 he directed The Model Couple, a science fiction fantasy about an apparently perfect pair “spied on, manipulated, and tested night and day” in a show apartment, which now stands as a peculiarly prescient vision of reality TV. Not for nothing, perhaps, did Klein and his wife, Jeanne Florin, appear as people of the future in Chris Marker’s celebrated 1962 film La Jetée.

In the 1990s, Klein went on to explore the links between photography and painting, making work that he painted on contact sheets. This work was both an evolution and a return to his earliest interests, because Klein started his artistic career as an abstract painter, studying in Fernand Léger’s studio in 1949 and exhibiting in galleries in Brussels and Milan. Klein’s work has been exhibited in institutions around the world but his current show at New York’s International Center of Photography has the pleasingly expansive title William Klein: YES – Photographs, Paintings, Films, 1948–2013, and goes some way to communicating the sheer breadth of his oeuvre and influence.

“For a long time, Klein was known as either a fashion photographer or a street photographer or a film-maker, as different audiences knew and valued different aspects of his work,” says curator David Company. “Only in recent years has the scope of his achievements begun to be recognised. Versatility runs against the idea that artistic significance is based on single themes and recurring preoccupations. But artists like Klein, who ranged freely and avoided specialism, are key to understanding the culture of the last century.”