If movies didn’t need to be publicised in advance, audiences would be able to go into Fresh feeling entirely, well, fresh. They could spend the first half-hour savouring this wry take on the frustrations of modern dating, starring Daisy Edgar-Jones and Sebastian Stan, without realising that the film was about to morph from Sleepless in Seattle into Saw. At least the director, Mimi Cave, has one trick that feels subtly disorienting even if you know it’s coming: she withholds the opening credits until the 33-minute mark. This delineates the two contrasting parts of the movie, while also expressing on a structural level the idea that something is very wrong. If this is the beginning of the film, then what exactly have we been watching until now?

Anyone who has gone the distance with Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Oscar-nominated Drive My Car will know the feeling. I saw the film in a crowded cinema where there were ripples of discombobulation when the opening titles appeared after 40 minutes or so. Back in the days of celluloid, there was always the possibility that the reels had been lined up in the wrong order, so it was amusing now to see those old analogue habits kick in, a few of us swivelling around in our seats to grimace at the projection booth.

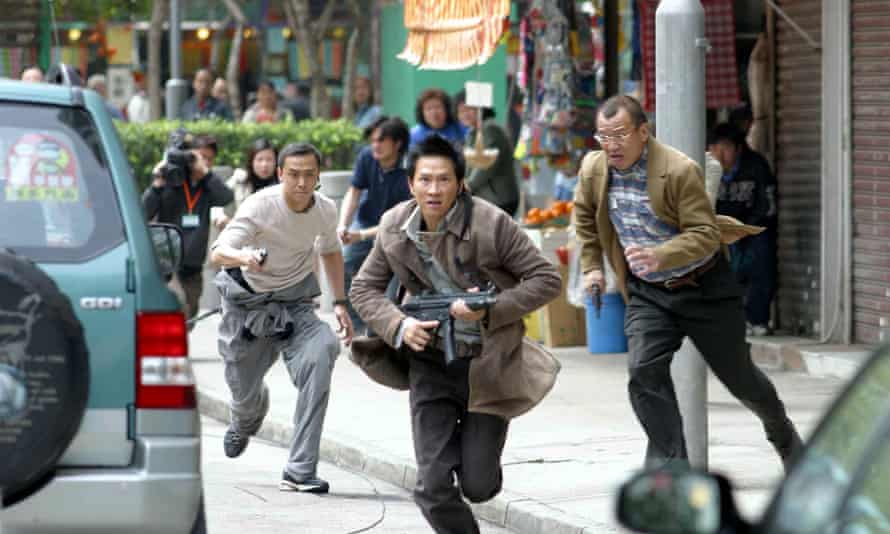

In reorganising the basic furniture of cinema, Cave and Hamaguchi bring a new kind of tension to the art of the opening sequence. Acclaim has always tended to settle disproportionately on those openers that exhibit clear technical prowess, such as the single-take shots that launch Touch of Evil, The Player and Johnnie To’s Breaking News. The last of those starts with a ferocious six-minute battle on the streets of Hong Kong, during which the camera rises repeatedly to sniper-level before returning to a worm’s-eye view of the melee.

Even mild bewilderment can be enough to snag our attention, as it is during the nearly wordless opening of Billy Wilder’s 1972 comedy Avanti! Why on earth has Jack Lemmon persuaded a stranger to swap clothes with him in the cramped bathroom on a flight to Italy? Seven minutes later, the lira drops. A serene spectacle can also work on an audience like hypnosis. There are no bombs, bullets or bathroom shenanigans in the eight-and-a-half-minute opening shot of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Flowers of Shanghai. The camera gazes sleepily at the various garrulous figures crowded around the candlelit parlour table in a 19th-century brothel. Tea is poured, games played, fans elegantly opened – and we’re hooked.

The options for an effective opening sequence are numerous, but what makes a truly great one? “The most successful openings are the ones that raise an audience’s curiosity or interest as opposed to providing them with information,” says the veteran editor Paul Hirsch. “But you have to be careful. There’s a difference between piquing someone’s curiosity and confusing them.”

Hirsch won an Oscar for his work on Star Wars (Episode IV: A New Hope), though he wouldn’t single out the beginning of that picture as an example to follow. “Star Wars opens with this crawl of rolling text on the screen. I always thought if we hadn’t had that, people would still have understood what was going on. I don’t think the best way to start a movie is to dump a load of information in the audience’s lap.”

More innovative are the 11 pictures Hirsch cut for Brian De Palma, including Sisters, Carrie and Blow Out. De Palma reserves a special contempt for directors who waste those precious opening minutes. “When you start a movie with a helicopter shot of Manhattan, or these boring drive-up shots showing a car driving up to a building – I mean, this is not an idea,” he said in 2010. “Especially the beginning of a movie when the audience is ready for anything. To waste that time with some boring geography shot mystifies me.” Hirsch recalls De Palma telling him: “If I ever shoot a drive-up, shoot me.”

Sisters begins with a man watching a blind woman start to undress after mistakenly entering a male changing room; Blow Out starts with a long point-of-view shot from the perspective of a killer. Neither sequence is quite what it seems – the first turns out to be an excerpt from a Candid Camera-style television show, the second a fake horror movie called Co-Ed Frenzy. De Palma has staged more complicated opening sequences (Snake Eyes begins with a roaming 13-minute shot which introduces the dramatis personae and sets up the plot’s central conspiracy) but it is his tactic of pulling the rug from under our feet when we have barely stepped through the front door that is so playful and pleasurable.

Many of Hirsch’s best opening sequences – he also edited Falling Down, which begins with Michael Douglas growing increasingly tense in a Los Angeles traffic jam – run for around five or six minutes. Is this the optimum time for a good opener, equivalent to the classic three-minute pop song? “I haven’t thought about it,” he says, with a shrug. “A sequence will tell you how long it needs to be. When you’re cutting, you keep going back to it and playing ‘What’s wrong with this picture?’ until you can’t find anything wrong any more.”

One advantage of a lengthy opening sequence is that it’s well-placed to create a narrative pause before the film proper begins. Think of the heart-breaking prologue in the Pixar animation Up, which compresses 80-odd years into 11 minutes, or the relationship that flares into life before dying out in the 18-minute opening of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

Back in fashion today is the sort of lengthy introductory flashback found more than 30 years ago in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. That giddy eight-minute opening shows how the film’s hero (played in his teens by River Phoenix) acquired his fear of snakes, his proficiency with a bullwhip, the scar on his chin and the fedora on his head. The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King starts with a flashback to the fateful day when Sméagol (Andy Serkis) began his transition into the monstrous Gollum. The most recent version of Death on the Nile begins by explaining why the Belgian sleuth Hercule Poirot (Kenneth Branagh) first cultivated his distinctive moustache, making the film not just a whodunit but a why-grow-it.

The most unorthodox use of the extended opening sequence in recent mainstream cinema was in No Time to Die. Though not the first James Bond film in which the hero is absent from the prologue (that honour goes to Live and Let Die), it is the only one to begin with a flashback to a supporting character’s childhood. Bond fans are accustomed to waiting an eternity for the opening credits sequence, but No Time to Die outstripped its predecessors: 24 minutes elapse before the title appears on screen.

It is only in this century that directors have truly begun to exploit the power of withholding that traditional marker of commencement. The credits for Benjamín Naishtat’s Rojo (2018), a tale of political turmoil in mid-1970s Argentina, don’t appear until 23 minutes in. “Starting the credits ‘late’ is so Brechtian,” says the film critic Charlotte O’Sullivan. “If a rule is tweaked, you naturally start to think about why it exists at all, which is a train of thought you suspect the directors of Rojo and Drive My Car would both applaud. After all, Drive My Car is about the need to do things differently – its hero stages Uncle Vanya in different languages – while Rojo is about the insidious effect of following rules blindly without thinking [about] whose interests they serve.”

A break or indentation of this kind also invites us to catch our breath. “Delaying the credits can be a way of creating an intermission,” says O’Sullivan. “That seems such an old-fashioned idea. But it’s bliss to have a moment to process information when there’s a lot to digest.”

If the structural oddness of Fresh and Drive My Car catches on, that sweet spot between 30 and 45 minutes could become the new normal for opening titles. Apichatpong Weerasethakul got there first, waiting three-quarters of an hour before running the credits for his enigmatic 2002 drama Blissfully Yours; Yoshihiro Nishimura followed suit in his grisly Helldriver (2010). No one seems to have gone quite as far as the Japanese provocateur Sion Sono: the titles in his indescribably madcap fantasy-horror-comedy-thriller Love Exposure (2008) fall at the 58-minute mark, with another three hours of action still to go. Of course, the original 1940 roadshow cut of Disney’s Fantasia dispensed with the convention entirely, which begs a philosophical question: if a film has no opening titles, has it ever really begun?