In the first five minutes of the late artist Ntozake Shange’s masterwork, for colored girls who have considered suicide/ when the rainbow is enuf, a character makes plea of witness and recognition:

“somebody/ anybody

sing a black girl’s song

…

bring her out

to know herself”

for colored girls, as a work, is the answer, a cannon-creating work that blends poetry and movement, along with other storytelling elements, to illuminate the lived experience of Black women. First conceived in 1974, the play is rightfully revered as one of the most important pieces in theater to date, but also for its unquantifiable influence.

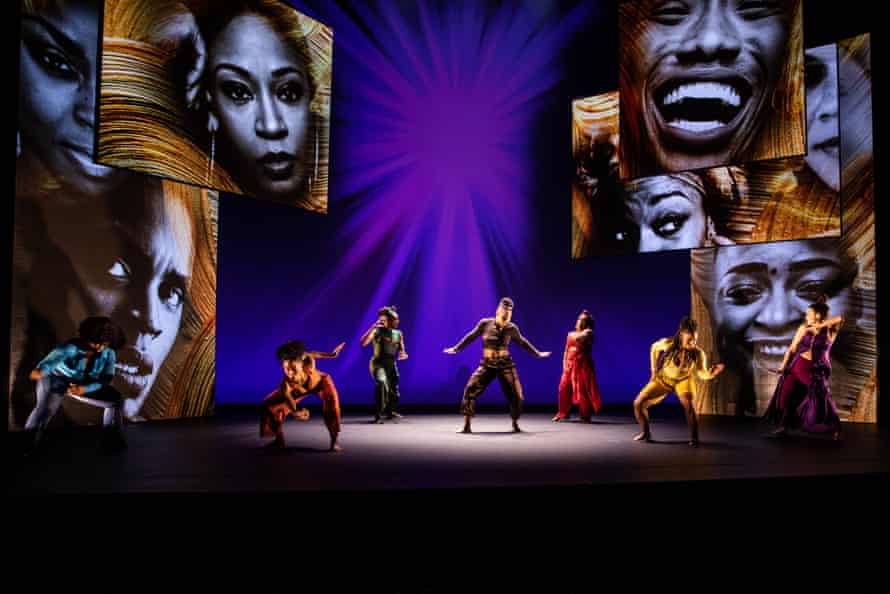

More than three decades after its 1976 Broadway run, the first Broadway revival of for colored girls has launched, directed and choreographed by Camille A Brown, the first Black woman to direct and choreograph a Broadway show in 65 years. The most recent run has garnered seven Tony award nominations, including best revival of a play and best direction of a play for Brown.

Brown’s connection to for colored girls dates back to childhood, when her mother would repeat the phrase “don’t let anyone take your stuff away,” in reference to a monologue featured in the show by lady in green. Brown, whom Shange interviewed for her first posthumous work Dance We Do, now leads the show’s first Broadway revival and is excited that audiences get to experience Shange’s timeless work.

“Even though the show is over 40 years old, it still speaks to today, and it can still tap into and connect with Black women, but also other people too,” said Brown.

for colored girls follows a cast of Black women – lady in red, lady in orange, lady in blue, lady in yellow, lady in green, lady in brown and lady in purple. The seven are scattered across various cities, woven together by mutual stories of love, heartbreak, pain and other fixtures of Black womanhood.

“These women definitely go through struggles, but they persevere and they move through them. That is what is [an] important and empowering part of the show,” said Brown.

To reduce for colored girls to a play is an oft-repeated mistake. The lodestar piece isn’t just a culmination of monologues braided together in theme. Rather, for colored girls… is a choreopoem, “a combination of all forms of theater storytelling,” said Leah C Gardiner in a 2019 New York Times interview. Gardiner directed a 2019 revival of the show at the Public Theater in New York City.

As they retell their stories, the women dance and stomp, laugh and cry as individuals, yes, but also as a flock. Almost no story is shared in total isolation, with even singular anecdotes receiving snaps and “mms” from the women on stage, hues of empathy and community care dashed throughout.

But amid the show’s tragedies, for colored girls also embraces a levity often missing from depictions of Black womanhood. Humor is central to Shange’s work, with Brown using school yard games that many Black women will find familiar, references she also imbues in her 2015 work Black Girl: Linguistic Play, a reference piece for this mounting.

“We go through spectrums,” said Brown in reference to embracing the joy in Shange’s piece. “We go through pain, but we also go through joy too, and there’s so much within one poem that goes from feeling like it is maybe low and painful, but then a reclamation happened.”

To trace the origins of for colored girls, one has to go to Bacchanal, a feminist bar near Berkley, California. In December 1974, Shange would share short readings of her poetry, as dancer Paula Moss danced with musical accompaniment. Influence of the Black Arts Movement and her time at the Sonoma State College’s women’s studies program, Shange channeled her own personal trials into a fusion of dance, poetry and music that were the building blocks of for colored girls.

Later on, Shange’s poetry readings expanded to include five other women who choreographed to Shange’s words.

“We were a little raw, self-conscious [and] eager. Whatever we were discovering in ourselves had been in process among us for almost two years,” said Shange to the Washington Post in a 1977 interview.

After a run in the Bay area, with Shange’s drafted work drawing niche interest, Shange and Moss traveled to New York’s Studio Rivbea, a jazz performance loft, to perform the dance-poetry. There, a version of the show, structured more into a play, was workshopped and mounted at the Public Theater, off-Broadway, before making a Broadway run in 1976 at the Booth Theatre.

Then and now, for colored girls is most regarded for giving rare, authentic insight into what it means be a Black woman, “a metaphysical dilemma”, Shange wrote. Written and portrayed by Black women, for colored girls laid bare truths on the blighted intersection of misogynoir, not as an educational tool for white audiences, but for Black women to see the full breadth of our experiences on stage.

“It wasn’t about trying to teach people about who [these] women are. It was about creating a safe space for Black women to hold space for each other, and express who we are and how we interact with each other,” said Brown.

Brown added: “It’s a Black woman’s voice, and Black women are seeing reflections of themselves.”

For colored girls has also inspired a generation of Black theatermakers, specifically Black female playwrights who embraced Shange’s unabashed truth telling and dedicated focus to Black women.

“She very much encouraged Black women to appreciate the fullness of themselves and to speak from their perspectives, not trying to fit into anyone else’s structure,” said playwright Ngozi Anyanwu in a 2018 Times interview.

Amid the show’s early closing, Brown says that she encourages audiences to see the production while they still can and be touched by Shange’s work.

“I was hoping that people would see it as movement and text working together in order to share these very important, very vulnerable, very spiritual and ritualistic stories,” said Brown.