I came to the United States when I was 3 years old. Today, I am one of some 600,000 people living under the precarious protection of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA. While it may not be easy to tell, DACA recipients and undocumented people suffer — usually in silence — from the personal consequences of policy dysfunction: we deal with depression and anxiety resulting from decades of uncertainty, terror, and rejection. I know personally that more has to be done to address the tremendous toll that DACA takes on the mental health of young people.

My whole existence in the US is fragile.

I was born in Zacapoaxtla, Puebla, Mexico, a beautiful city known for its architecture, food, and pottery. But before I could even start elementary school, my parents decided to move our family to the United States. The trip was dangerous, as it is for anyone who comes to the US without a visa. For a week, my 6-year-old cousin and I were separated from our parents. We were just children — alone and scared.

Although that was two decades ago, the trauma of that experience will never leave me. I now live in Brooklyn, which is beautiful in its own way, but I cannot settle down and make a home of this place because my whole existence in the US is fragile. With every failed attempt to permanently protect us, DACA recipients are again and again left to deal with the mental and emotional toll of an unknown future. DACA protects those in the program from deportation while offering us permits to work legally in this country. However, its temporary nature means it is subjected to threats, including a current court challenge.

And now, reflecting on my childhood, I see that I carried a lot of other heavy obligations. My parents prepared me for the duality of being a DACA recipient: I could get a license and go to college, but if my parents were deported, I would be responsible for my younger brothers who were born in the US. My protected status meant I could legally work, but that reality also placed the role of potential financial provider squarely on my shoulders. The anxiety and stress of being parentified is true for many in my community, and it is untenable.

There is a saying that encapsulates the lack of belonging we feel: “Ni de aqui, ni de allá,” which means neither from here nor there. Sometimes, I hear our elders say we are becoming Americanized — but it’s not true. We are still trying to preserve our language and culture while also honoring the lives we are creating in this country. For immigrants, developing a sense of belonging is nearly impossible even though the US is a home we have come to know as ours.

Like many DACA recipients, I am an expert in navigation. From leaving one country and entering another to background checks every two years, we learn to navigate uncomfortable experiences and harsh realities. But this skill comes at a price. In a study of the health consequences associated with DACA, researchers found 25 percent of recipients reported moderate psychological distress. During my senior year of college, I was diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety Disorder and PTSD. My therapists helped me identify the root cause of those diagnoses: my experience coming to this country, the instability of DACA, and the fear that the life I am building here can be ripped away at any moment.

Mental health support is often too inaccessible for how essential it is.

What can be done to address the particular mental health challenges of DACA recipients and allow us to heal? First and foremost, we need permanent protection and a path to citizenship now — one that is equitable and permanent for everyone, including undocumented people regardless of age. One study found that not only does providing permanent protection promote the well-being of adults, but it also improves the overall mental health of their children. Such protection is a matter of human rights; it would improve our wellness and safety for generations, allowing us to flourish and contribute fully to our adopted home.

While obtaining permanent legal status is the most crucial step in alleviating the fear and anxiety millions of people are dealing with, the country must do more to meet the current mental health needs of DACA recipients. We often face racism and discrimination, so finding accessible mental health professionals skilled in trauma-informed care and working with communities of color is essential. Thankfully, there are some resources taking shape. Latinx Therapy’s directory allows DACA recipients and Latinx folks to filter their search for a therapist by state, cultural identity, and other specialties. Inclusive Therapists helps marginalized communities safely find therapists and counselors who celebrate our identities. And United We Dream, the largest network of immigrant youth-led, has a collection of free tool kits designed to help transform anxieties and insecurities. But free resources like these are few and far between; they need to become the standard and easy to find.

Mental health support is often too inaccessible for how essential it is. Because we have challenges finding providers who understand the cultural norms and sociopolitical experiences that shape our lives, trusting the right person with our trauma and healing can take time, money, and multiple therapists. It took me a couple of years to find a therapist I could confide in and trust. My second therapist was Latina and also understood the pain and confusion of being parentified. When I struggled to find the right English words to talk about how I felt, she created a safe space for me to talk in Spanish and would often help me navigate those language barriers.

When we think about healing, sometimes turning inward can help. Our communities can do more to support each other across generations. Elders and young people often compare their traumatic experiences, setting up hurtful “I suffer more than you do” contrasts. Many elders come from a time when mental health needs were severely stigmatized, but they still of course carry the weight and trauma of their own experiences. We need to hold space for each other to talk about the grief of existing between two places and our rage at constantly feeling like chess pieces in a political game. This can help facilitate healing that can only happen within our community.

DACA recipients are exhausted and traumatized by the constant threats to our safety. We are no longer children with no choice but to follow the instructions of adults around us. We are adults, and we demand more for ourselves and our fellow undocumented community. The constant onslaught of new developments about DACA’s future feels like a roller coaster of hope and hopelessness — a ride none of us asked to be on. Because of that, therapy, rest, and distance are the tools of resistance I use to show up for myself and my people. As we continue to call on lawmakers to first do the right thing, we must remember that prioritizing our mental health and taking care of ourselves and each other is part of the fight.

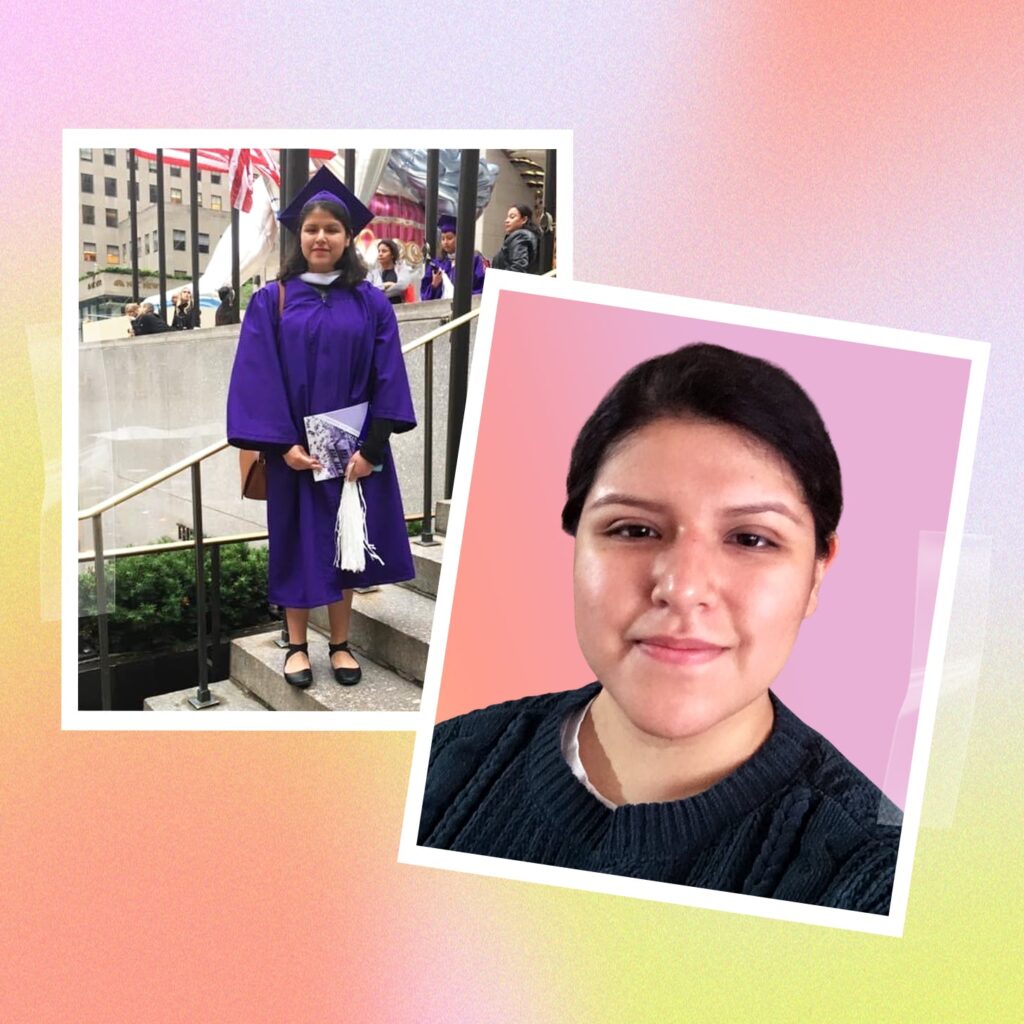

Image Source: Courtesy of Rosio Santos Castelan and Photo Illustration: Michelle Alfonso