For anyone lucky enough to have experienced the long arc of his career, the death of droll, dry, deadpan Martin Mull, Thursday at 80, feels like the end of an era. A writer, songwriter, musician, comedian, comic actor and, out of the spotlight, a serious painter, Mull was a comfortingly disquieting presence — deceptively normal, even bland, but with a spark of evil. Martin Mull is with us, one felt, and that much at least is right with the world.

There was a sort of timelessness in his person. As a well-dressed, articulate young person, he seemed older than his years; in later years, owl-eyed behind his spectacles, he came across as oddly boyish. He leaves behind a long, uninterrupted string of screen credits, beginning with Norman Lear’s small-town soap-opera satire “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman” and including a regular roles in “Roseanne” and “Sabrina the Teenage Witch,” recurring parts on “Veep” and “Arrested Development” and guest shots ranging from “Taxi” to “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit” and in such films as “Mr. Mom,” “Clue” and “Mrs. Doubtfire.” And so it seemed he would always be around, and working. Even so,his appearances were never quite expected, or in the expected place. But he was ever welcome, and always right for the job.

Like Steve Martin, his friend and junior by a few years, he was an accomplished instrumentalist; as a purveyor of witty comic songs he was in the tradition of Tom Lehrer and Flanders and Swann and a peer of Dan Hicks, with whom he shared a taste in floral-print shirts. He was a countercultural cabaret artist who set himself apart from the counterculture and, again like Martin, he dressed well in an age when younger comics let their hair grow long and wore street clothes to distinguish themselves from their suit-and-tie elders.

But where Martin was a flurry of flapping arms and legs, Mull worked from a place of stillness; indeed, his early appearances found him seated. His musical stage act, christened Martin Mull & His Fabulous Furniture, found him in his signature prop, a big armchair, leaning forward over his big, hollow-body guitar (“Ever seen one of these before? It’s electric. You’ll be seeing a lot of those in the near future”). Later, he leaned back as Barth Gimble, the host of the talk show parodies “Fernwood 2Night” and “America 2Night.” Even his solo spots on “The Tonight Show,” on which he was a reliably hilarious, blue-streak-talking guest, usually playing off his career in show business, were delivered sitting.

On “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman,” Mull played Garth Gimble, an abusive husband who died impaled on the star of a Christmas tree; one would say that Garth had to die in order that Barth, his twin brother, might live. On the spun-off “Fernwood 2Night,” Mull as Barth and Fred Willard, as confidently dim sidekick Jerry Hubbard, created a telepathic double act in which they could seem antithetical expressions of a single character. Together, the talk shows lasted only two summer seasons, but due to their weeknightly appearance — they adopted the form of the thing parodied — produced 130 episodes, giving them cultural weight. (You may find them extracted all over the internet.) Mull and Willard would work together again over the years, in Mull’s Cinemax series “The History of White People in America” and the follow-up feature “Portrait of a White Marriage,” in commercials for Red Roof Inn, as a gay couple on “Roseanne” and as robots on “Dexter’s Laboratory.”

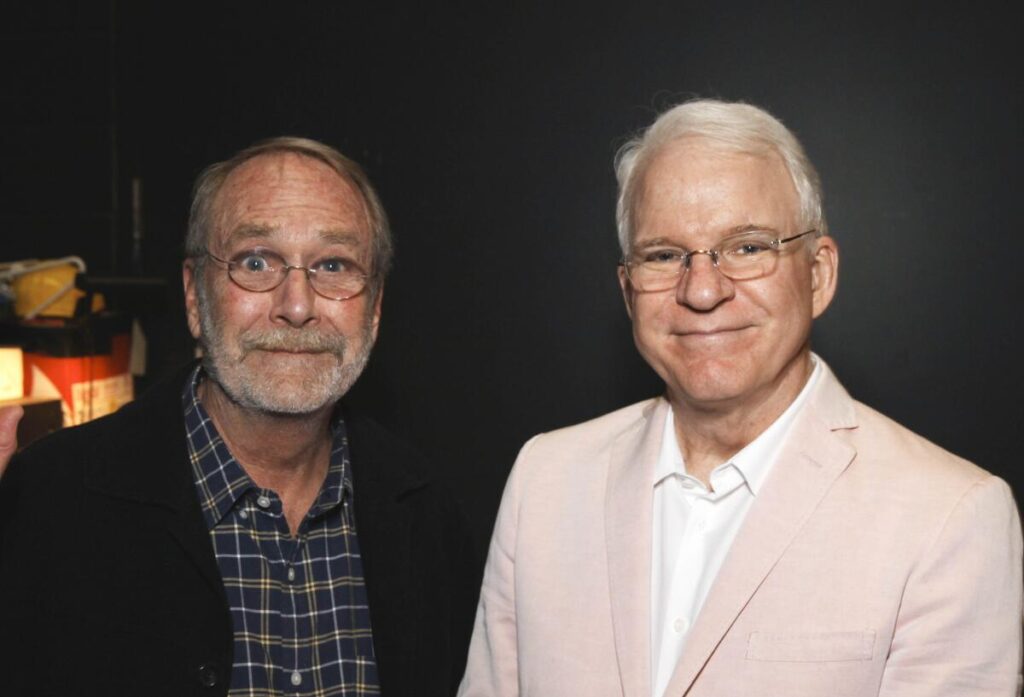

From left, actor Martin Mull and Steve Martin pose during The Un-Private Collection: Eric Fischl and Steve Martin, an art talk presented by The Broad museum and held at The Broad Stage on Monday, June 23, 2014, in Santa Monica, Calif.

(Ryan Miller / Ryan Miller/invision/ap)

Mull grew up in North Ridgeville, Ohio, not far from Fernwood in the map of the imagination, and white insularity was a theme in his comedy. My first Mull memory came with the 1973 album “Martin Mull & His Fabulous Furniture in Your Living Room!,” which opened with a version of “Dueling Banjos” played on tubas and included a “Lake Erie delta” blues song, purportedly learned from his real estate agent grandfather; it was performed on a ukulele with a baby bottle used as a slide: “I woke up this afternoon/Both cars were gone/I felt so low down deep inside/I threw my drink across the lawn.”

“The History of White People in America,” he told David Letterman, would examine “what, if anything, has the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant done in this country since World War One. It’ll be taking a pretty good hard look at that.” A memorable episode of “Fernwood” exhibits a Jewish person stopped for speeding as he passed through town as something of an exotic animal, for the benefit of Fernwoodians who may have “actually never seen a real live Jew before.” “I hope that seat’s all right,” Barth says, welcoming his guest. “ I’m not sure what you’re used to.”

Like many great comedians — the Marx Brothers and W.C. Fields before him, or Martin and Albert Brooks in his own time — Mull was a temperamental outsider who achieved the success of an insider, while remaining essentially untamed. It’s not beside the point that he was, from first to last, a serious artist, with undergraduate and graduate degrees from the Rhode Island School of Design — where, it does not seem too coincidental to mention, the Talking Heads, were later born. He would refer to show business as a “day job” that allowed him to pursue painting.

We were lucky he needed the work.