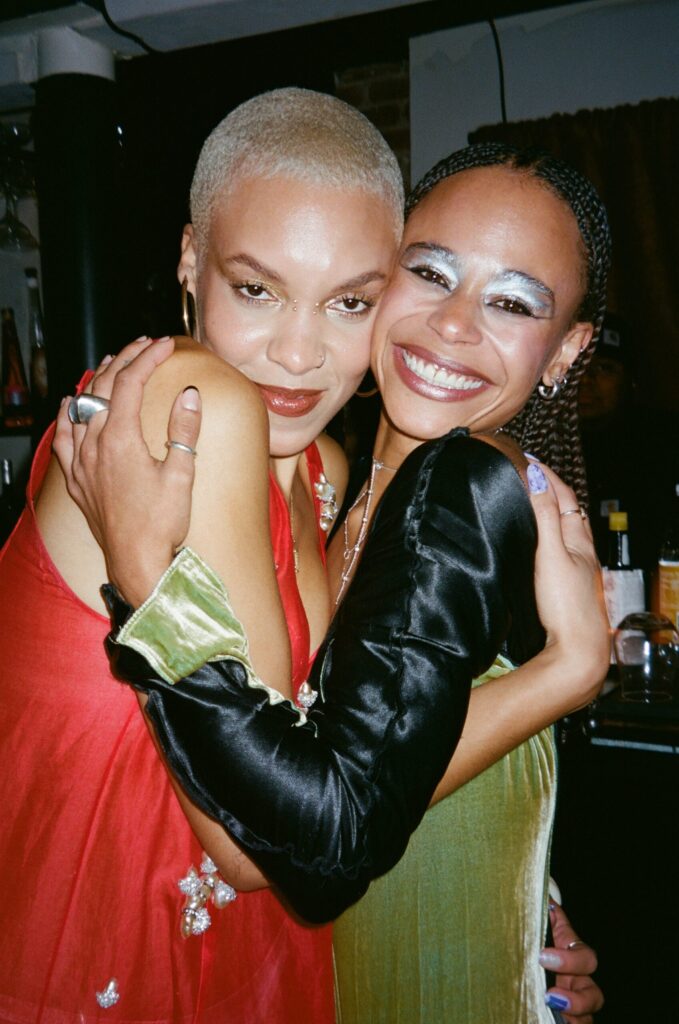

Exactly one year ago, Camille Bacon and Daria Simone Harper met for dinner. Having admired each other’s work from afar, both with distinguished careers in art and writing, they commiserated on the glaring issues they saw in the publishing landscape: dismal pay, rapid-fire deadlines, a lack of representation, and parameters that leave no room for play. From the outset, they sought to make a magazine that champions the depth that smart arts criticism demands. “We want our publication to be like water, like it shapes to whatever container you put it in,” Bacon said as the music got going at the launch party of their new quarterly publication, Jupiter. Inspired by the methodical exhibition cycles of institutions like 52 Walker and the mission of other publications like ARTS.BLACK, the co-editors want to create a home for writing that is expansive, even galactic. Featuring a cover essay by Akwaeke Emezi, with contributors like Jenna “J” Wortham and Diallo Simon-Ponte, much of the inaugural issue coheres around the theme of music. Last Thursday, in the back room of Lula Mae in Clinton Hill, the pair slipped away to tell us about alignments both natal and creative.

———

ELOISE KING-CLEMENTS: How long has this night been in the works?

CAMILLE BACON: Exactly a year.

DARIA SIMONE HARPER: A whole year. The launch, we mapped it out unintentionally, but we still feel that it was ultimately very ordained. Things have come to fruition exactly a year from when we first sat down for dinner, and that dinner planted the seeds for what the publication would be.

KING-CLEMENTS: Tell me about that dinner.

HARPER: We wanted to just sit down to just spend time with each other. We’ve been admiring each other’s work in different kinds of practices and perspectives from a distance. Eventually, we crossed paths in person and were like, “We need to sit down.” We cracked a lot wide open when we were able to just share about our experiences as writers within the visual art space. These are conditions that we feel are quite oppressive, and that’s really led to the type of depth and exploration of work or exploration of artists in the art space.

KING-CLEMENTS: We don’t need to dwell on the negative, but can you talk just a little bit about the conditions that you guys felt you wanted to change?

HARPER: Absolutely. Of course, in this conversation we commiserated, we were sharing a lot, but we boiled it down to the fact that writers are not paid enough, simply put. Really, really low compensation for thousands and thousands of words, not to mention all the interviews.

BACON: You understand.

HARPER: Often publications and different platforms expect writers to perform at breakneck speed. A lot of publications are setting up the status quo and expecting writers to just fit within that. There’s this precedent of going to a show and then a day or two later, being expected to contribute some 2,000, 2,500, 3,000 words on it. That’s often just something that ultimately cannot be grappled with or really explored in its whole entirety.

BACON: Or you’re given like 500 words to write about something that is too galactic to be boiled down.

HARPER: Yes, we were thinking about this kind of flattening or chunking that happens and all that’s lost when you have to fit within these requirements they set.

KING-CLEMENTS: Making it bite-sized. What were some of those initial examples that you looked to for references or inspiration?

BACON: There were definitely comps in terms of publications that we would like to model, but really one, and it’s ARTS. BLACK, which was started by Taylor Renee Aldridge and Jessica Lynne. It was actually the first journal dedicated to Black art critics, and it was started a decade ago.

KING-CLEMENTS: Wow.

BACON: To imagine all of that time can elapse and it takes until essentially like, 2013 for a journal of this nature to come to fruition is kind of mind-boggling. We really followed in their footsteps. ARTS. BLACK is a major one, but I would say the other comps are not publications. We’re looking to 52 Walker, which is a gallery run by Ebony Haynes, part of David Zwirner, and thinking about this quarterly exhibition schedule versus every six weeks. What does it mean to sit with a practice and diligently research it for that much time? How does the show look different, and how does it feel different if you allot that amount of time to ideate and mull in the thing? The other one is Saint Heron, which is Solange’s creative agency. Thinking about the range that she has, she just released a glass-blowing collection. We have ambitions for Jupiter to be a magazine now but to grow it into an institution in the future, where we can have residencies.

BACON: And workshop spaces, a library.

KING-CLEMENTS: Can you just tell us about the ethos of Jupiter? Where does the name come from?

BACON: We announced that we were doing this in April in Chicago on a panel with Amari, who’s DJ-ing tonight. It’s a wonderful full-orbit moment. In April, we had not decided on a name yet. We knew that it would come, rather than sitting down to brainstorm a name together in this rigid way. We know that names are spells, incantations, so we really wanted to name our publication something that would guarantee that, every time we spoke it, it would breathe into a long lifespan of what we’re doing. It very much so felt like it was coming from elsewhere, from something grander and larger than what currently exists on Earth. One day, I woke up and just heard “Jupiter” over and over and over again, and I put it in one of our planning documents and just went back to sleep. I woke up the next morning and started thinking about it more, and was like, “Jupiter is the planet of expansion, abundance, love, good fortune, long lifespan.” It also is an entirely gaseous and liquid planet, so while it orbits in the same way that Earth does, it still feels kind of mystical and mysterious and also really malleable. We want our publication to be like water, like it shapes to whatever container you put it in.

HARPER: With our natal charts each being heavily oriented by Jupiter, I felt that it really resonated with us personally, but that also spoke to this element of malleability and also elasticity that we really need to embody with the publication.

KING-CLEMENTS: How did you go about finding your first contributors? I’m sure you had a lot of pitches.

BACON: We don’t actually accept pitches because we pay our writers so much more than most publications, we have to directly commission people at this point until we get more major seed funding, essentially. It all started with Akwaeke Emezi and their book, Dear Senthuran: A Black Spirit Memoir, where they named this term “world-bending.” We were really attracted to that language because people talk about “world-building” a lot, but it feels like it carries this association that we have to just obliterate everything that exists and then construct on top of it. There are certainly things that need to be obliterated, but there is also so much that we have, resource-wise, both metaphysically and materially, that it’s just a question of slightly altering the direction that it flows in. It was a no-brainer that we wanted Akwaeke to author the cover essay. I am delightfully surprised that a lot of the pieces orbit around music. Obviously, Joshua [Segun-Lean’s] essay moved from this centripetal point of Keith Jared’s music; J [Wortham’s] essay is orbiting around this idea of opera as a way to express the ineffable; Diallo [Simon-Ponte’s] essay thinks through a Ghanaian guitarist named Mamady. It was like Akwaeke formed the column, and then the house kind of just assembled and built itself around that.

HARPER: It serves as the pillar for the kind of conceptual framing of each of these other contributors, but they also dance and flow and extend each other’s lines of inquiry without that set intention to really deepen this sense of the world-bending capacity of art.

BACON: I’d add one more thing, which is the joy of working together, which is the joy of really having felt like I have met my life partner in all things collaboration. I think a lot of people, when they do things together, are like, “There’s no way I could’ve done this by myself,” but really, truly there’s no way. All these logistical, rigorously annoying things that we had to work through, we had so much fun. We’re giggling talking to our lawyers and our accountants.

HARPER: We talked about this with her mentor the other day, and she’s like, “I cannot believe that you all had fun going over your budget”

BACON: We’re like, “We did.” It’s the effervescence that Daria brings to all of our meetings that I think really allows me to have a new relationship with joy as it relates to my work. I think our relationship is what allows the publication to be as generous as it is, because we’re so generous to one another.

HARPER: Absolutely.

BACON: I love you.

HARPER: I love you.