Imagine, if you will, that you decide to take a break from your heathen lifestyle and visit an art museum. You pass through different wings, and most of them make sense. Your ego is growing by the minute as you congratulate yourself on your intelligence and class. You hand out a generous, but metered amount of appreciative nods as you pass marble busts and ancient portraits of kings in puffy dress. Until you enter a hall that’s filled with art that suddenly triggers your impostor syndrome. It’s an exhibit on surrealist art, and you, to quote Tim Robinson, don’t know what any of this shit is.

Which of course, is part of the point. The whole goal of surrealism is to explore the subconscious, so no straightforward painting is ever going to get hung in there. Still, you feel like a sham observing these supposedly incredibly meaningful works while a little analytical fellow in your brain shrugs its shoulders helplessly. Now, let’s add one final piece to this nightmare pie: A small child tugs at the hem of your jacket, and asks, “What does it mean?” Suddenly, a pair of eyes and the parents to go along with the, is staring at you, wondering if you have any idea what the hell is going on.

But if you read this article, and stand in front of one of these five paintings, you just might…

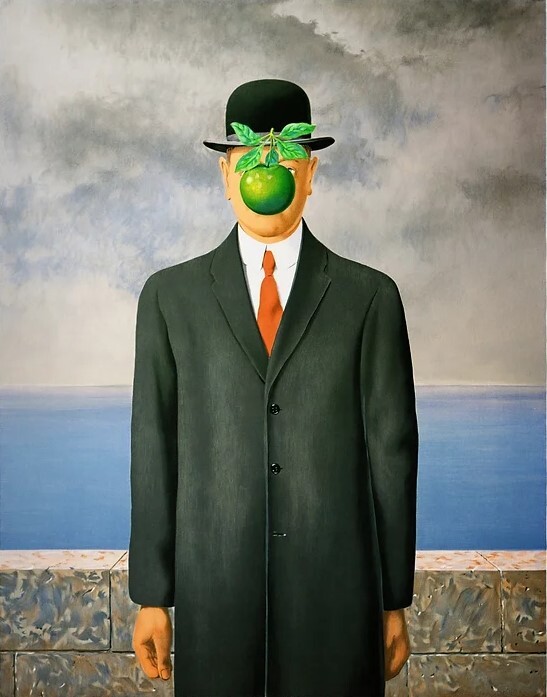

The Son of Man, Rene Magritte

Rene Magritte

Possibly the most famous surrealist work of all time, by one of the most famous surreal artists is The Son of Man by Rene Magritte. Or as most people know it, “the guy with the apple for a face.” It’s an image you’ve probably seen before in some sense, or as part of an intellectually masturbatory Halloween costume.

As for the meaning, you can probably get in the ballpark all on your lonesome, that it’s about something being hidden. Thankfully, Magritte himself was nice enough to lead everyone the rest of the way in a radio interview, explaining, “It’s something that happens constantly. Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see.” He further references a “quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict” caused by our desire to see both the apple and the face beneath.

Feel free to spit that all out at the next person you see with it on their iPhone case.

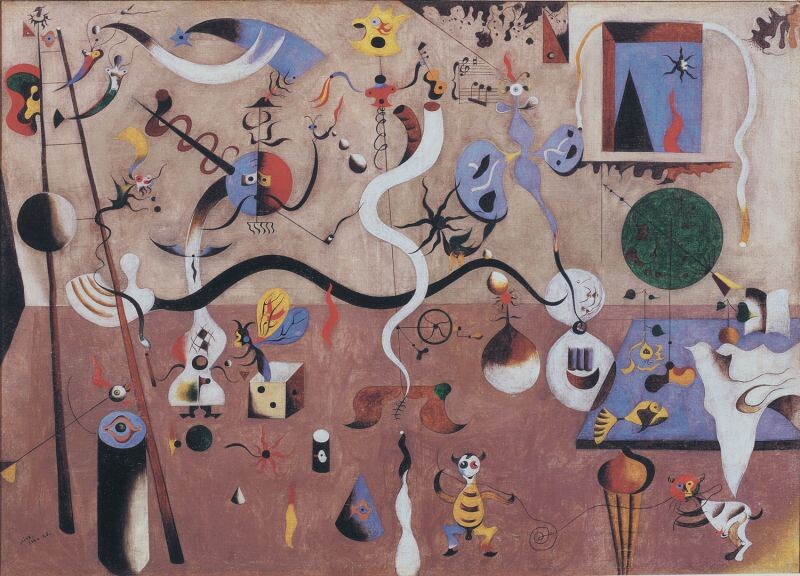

The Harlequin’

s Carnival, Joan Miro

Joan Miro

Some of Joan Miro’s works can inspire even stronger intellectual feelings of “oh no.” Unlike Son of Man, we don’t even have many recognizable figures to go off of. Sure, there’s a freaky looking bee coming out of a die, but that’s probably not helping that much. In this case, the fact that the whole thing feels like it’s making you go ever so slightly insane was very much on purpose. Miro was very literally a starving artist for much of his life, and it was an attempt to record the feelings and visions from starvation.

Or as Miro put it, “I tried to translate the hallucinations that hunger would produce. I didn’t depict what I’d see in my dreams, as the Surrealist often did, but what hunger would produce: a form of trance.”

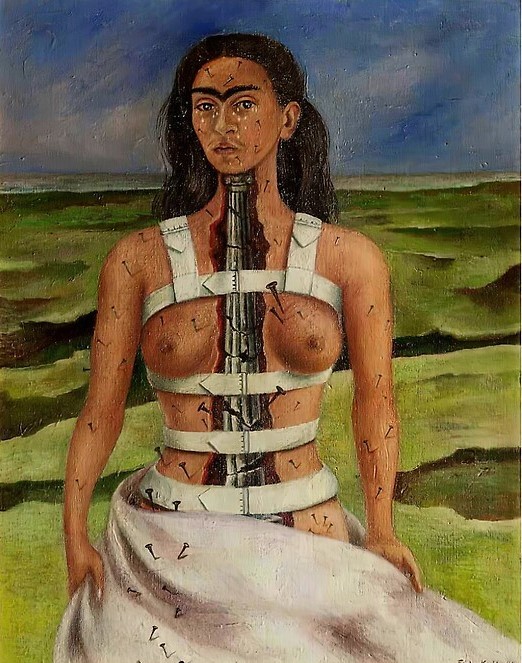

Broken Column, Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo

It turns out that, even if you beat all imaginable odds to achieve mastery, recognition and success in the art world, if you have a unibrow, that’s going to be the main thing you’ll be remembered for. You’ll also get played by Salma Hayek in a biopic, which is nice. Not that Frida Kahlo ever got to witness it. Her self-portrait Broken Column is a little more literal than others on this list. For example, you can probably intuitively guess that she wasn’t having a great time. You would be right!

The painting is a reference to Kahlo’s life, which was dominated by physical disability and pain. She developed a limp from polio, only to have that followed up with a bus accident that impaled her with a metal pole and left her permanently disabled. The unsteady, damaged column represents her spine, and the nails, well, that’s a pretty straightforward representation of pain.

Ubu Imperator, Max Ernst

Max Ernst

Now look, here’s a painting that I think we can all agree, meaning aside, absolutely rules. This dude looks awesome. You could have told me it was an attempt to invent a beloved Dark Souls NPC and I’d believe you. This kick-ass, topsy-turvy fellow is, in fact, filled to the brim with symbolism. The artist, Max Ernst, saw a play by Alfred Jarry called King Ubu and used it as inspiration. The idea of a hulking, armored fellow, balanced precariously on a pinpoint tip, is a statement on the instability of authority.

The Meal of Lord Candlestick, Leonora Carrington

Leonora Carrington

Seeing some surrealist paintings, you might think to yourself, “This person must be clinically insane.” That’s a small-minded and insulting assumption most of the time, and maybe an admission of lack of imagination. Leonora Carrington, however… Well, yeah, she had a couple screws loose, though living her life fleeing the Nazis would do the same to most people.

The Meal of Lord Candlestick gives us a hint that she had a rough go of it from the beginning. “Lord Candlestick” was a nickname Carrington had for her father, and the table in the painting is based on one from her childhood home. That combines with her disdain for Catholicism, the less-than-easygoing religion she was raised in. When somebody in a painting is eating a baby, that’s not generally a sign of fondness.