If you think learning history just means memorizing a bunch of old names, you’re wrong. And we don’t mean history is full of interesting stories that are fun to learn about. We mean that you memorized the wrong old names. Because many of the names we associate with figures from history aren’t the right names at all.

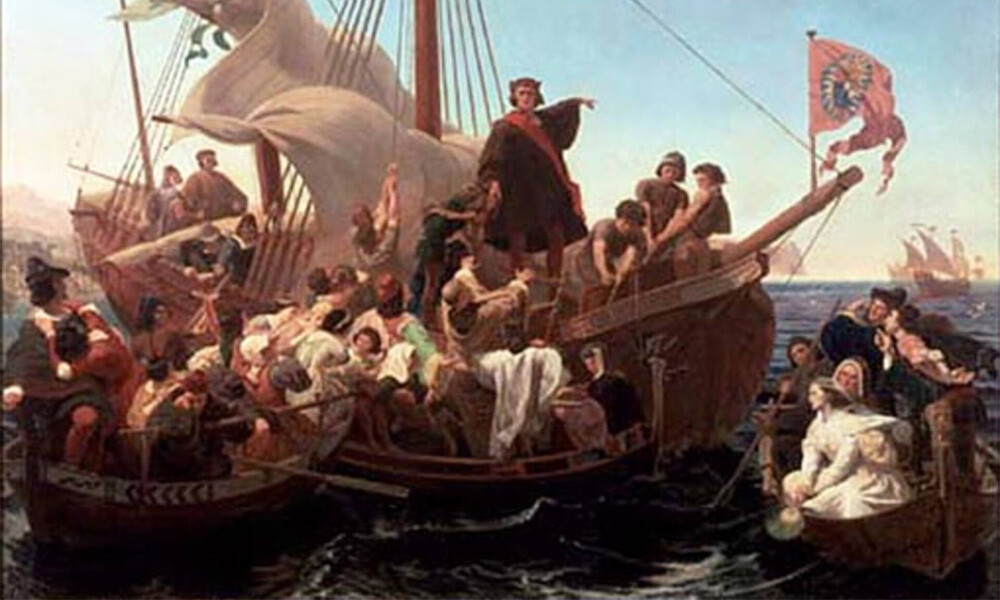

The Niña and the Pinta

Every American schoolchild is taught to list the three ships that sailed to the New World as part of Christopher Columbus’ first voyage: the Niña, the Pinta and the Santa Maria. At least, that’s what schools taught back when we were little kids. Back then, they also taught that Columbus discovered the world was round, so we can only hope someone has updated the curriculum since then.

But yeah: We were taught “the Niña, the Pinta and the Santa Maria,” saying those names always in that order. And yet, the first of those ships wasn’t named the Niña. It was named the Santa Clara. “La Niña” was its nickname. And there’s nothing wrong with calling a ship by its nickname, but if we’re going to call that ship the Niña instead of its saint’s name, you’d think we’d do the same for the Santa Maria and use its nickname, Marigalanta.

The only reason we stuck on Niña and Santa Maria appears to be that those were the names used in Washington Irving’s A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus. That’s the same book of historical fiction that spread the myth that people in the 15th century thought the world was flat.

As for the Pinta, that one’s even funnier. “Pinta” was a nickname as well (it translates as “the painted one,” meaning “whore”), and with this ship, we don’t have any record at all of what the official name was. This sort of goes to show how ship names aren’t that important, which makes it all the more silly that these three ship names are a part of every child’s foundational education. Kids can’t name a single person on that voyage other than Columbus, or name where Columbus landed, but we damn well make sure they can recall “the Niña, the Pinta and the Santa Maria.”

Plato

Everyone can name a few Greek philosophers, even if they don’t know a thing about history. There’s Socrates, there’s Aristotle and there’s Plato, and you don’t need to have any idea which one of them taught whom to know those three names. Though, with that last one, you probably don’t know his real name. Plato was born with the name “Aristocles,” which conveniently sounds like a mixture of Aristotle and Socrates.

Aristocles is called Plato because his wrestling coach gave him that as a nickname. Platon meant “broad,” so that’s what the coach called him. Someone basically dubbed him “big guy,” and that name stuck. This is a fine reminder, though, to build both your body and your mind. If wrestlers spent more time studying philosophy and philosophers spent more time wrestling, the world would be a better place.

The Colosseum

The Colosseum was not called “the Colosseum” in its heyday. Nor is “Colosseum” a translation of the name they used for it back then. We started calling it the Colosseum roughly a full millennium after it was built and many centuries after the last gladiator fights.

This name “Colosseum” likely comes from a statue that was placed near the amphitheater, a 100-foot tall colossus of the Emperor Nero. That statue did stand there during (part of) the time when the amphitheater was hosting giraffe fights and simulated sea battles, but no one referred to the place in terms of the colossus back then. They simply called it “the amphitheater.” It’s a fair guess that they also had some more specific name for it, but we don’t know what it is.

Some historians called it the Flavian Amphitheatre, after a dynasty of emperors from around then, but none of the people at the time called it that. We see some references calling it Amphitheatrum Caesareum as well, but other amphitheaters were called that too, always informally.

More than anything else, this uncertainty is distressing because the movie Gladiator refers to the building as “the Colosseum” a couple dozen times. Up till now, we’d been led to believe Ridley Scott never got history wrong.

The Great Sphinx

That last line was a joke of course — we see some creative license in Ridley Scott historical movies, such as Napoleon, which depicts the legend that Napoleon used the Sphinx as target practice. Napoleon didn’t do that, we know that. Weirdly, though, we don’t know much else about the Great Sphinx. We don’t even know what it’s a statue of.

We call it a “sphinx,” because that’s a word for a creature with a lion’s body and a human head. But a sphinx is a figure from Greek mythology, with wings and a woman’s head. That doesn’t describe the Great Sphinx. No one ever called that Giza statue a sphinx till thousands of years after it was constructed.

The oldest Egyptian name we see recorded for it is Horemakhet. This word does not refer to a marketplace for pintas but rather translates as “Horus-in-the-Horizon.” The god Horus was indeed sometimes depicted with a lion’s body and a man’s head, when he wasn’t in his more famous form, with the head of a falcon. This name, which was recorded some 700 years after the statue’s construction, fits with the best current theory about the statue: That it represents the Pharaoh Khafre as Horus.

You’d think “Horus” would make it into the current name for the sphinx, considering all Horus did for us (protecting the sky, tricking Set into eating his semen, etc). It’s like if people ended up calling the Christ the Redeemer statue in Rio “the tall dude.” Which, now that we think about it, is kind of what happened with several statues called “the colossus.”

Amadeus Mozart

We keep referring to the composer Mozart as “Amadeus.” There was the famous film Amadeus, based on a play by the same name, followed by the song “Rock Me Amadeus,” a new musical adaptation and a new limited Amadeus series currently in pre-production. You might be tempted to think the guy’s name was Amadeus Mozart, forgetting that his first name was really Wolfgang.

But Amadeus wasn’t his middle name either. The boy Mozart was christened “Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart.” You don’t need to worry too much about the “Joannes Chrysostomus” part, which are saints’ names, but even just sticking to the rest, you’ll see a conspicuous lack of Amadeus in there.

Later in life, Mozart called himself “Wolfgang Amadeo Mozart.” Amadeo is the Italian form of the Greek Theophilus, in that both might mean “lover of God.” At no point, however, did he ever call himself “Wolfgang Amadeus.” He did sometimes write his name down as “Wolfgangus Amadeus Mozartus,” but the thing you need to know about that name is it was a joke. He was making each part of his name as Latin as possible (even the Mozart part, which didn’t make sense) because that was funny.

That joke name lived on. It’s like if, one Halloween, you change your name online to stick the word “BOO!” in there. Centuries later, congratulations. That’s the title of your biopic.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.