“Blue for me is the colour of blockade, hunger and war …” said the Ukrainian artist Boris Mikhailov about the project he made in the early 1990s, the period that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union.

At the core of this cycle of PhotoBrussels is the story of Ukraine told both conceptually and literally through the eyes of three generations of photographers. Generations of Resilience reveals an artistic act of defence that opens with Mikhailov’s atmospheric and unsettling series At Dusk.

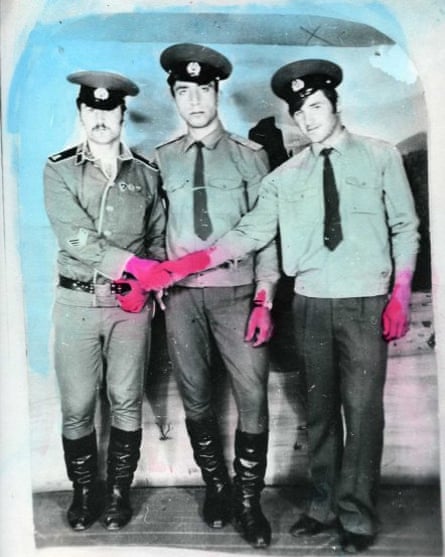

Each image, made in his home town of Kharkiv, is tinted with a cobalt blue wash, conjuring up a sense of cold hardship, a place where society is in a state of disintegration. His commentary at the time was not unilateral. From the oppression of the Soviet state rose a collective of artists and photographers sharing a visual language of protest, a distinct movement of opposition that became known as the Kharkiv School of Photography. They used their artistic expression to challenge the systems of the state, censorship, propaganda. Hand colourising images to give a sensational view of society for the greater good was a technique regularly used by Soviet state media to enhance their message. Mikhailov and his colleagues subverted the act to create satirical scenes that mocked the state, making a pantomime of their methods.

They took risks to state their challenges to society. Among them at the time was the young Yevgeniy Pavlov. He and his friends were self-confessed hippies during the 1970s, a time when Soviet convention frowned upon men wearing their hair longer, let alone public displays of affection or aspects of nudity. In an act of joyful defiance for which they could easily have been detained by the authorities he and his friends made their way to a local lake in the dead of night and there they gleefully removed their clothes, accompanied by the sounds of the violin while Pavlov photographed them creating an unparalleled series at the time that revels in freedom.

Documentary has played a significant part in recording a country emerging from Soviet rule. In the mid-1990s a young Alexander Chekmenev was hired by Ukraine’s social services to take passport pictures for public records of the ill and elderly who were unable to leave home to do this for themselves. Witnessing how people were living made a strong impression him, now a globally recognised and awarded photojournalist, his practice is always to put ordinary people at the heart of his stories.

Much of this early work from the Kharkiv School of Photography has been rescued from the recent bombing of the city. Teams of volunteers organised the safe passage of boxes of archive material in the empty holds of aid lorries leaving the country after depositing supplies.

The protection of Ukraine’s cultural heritage in the time of war has been a primary concern for many including Elena Subach who has made a striking series showing the measures taken to protect sculptures, artworks and artefacts in Lviv, a city that is more than 700 years old and is one of the major cultural hubs in the country.

“Since the beginning of the war, we have all changed, searching for a role where we can be as effective as possible,” says Subach. “Before the war one of my favourite mottoes was ‘if there is no magic in art, then it is just media’ … But now my approach to photography has become a clear documentary. I document the present, because history in its concentrated form is unfolding here and now.”

Finding a sense of purpose for the younger generation of photographers in Ukraine is a genuine concern when many of their peers have been displaced by circumstance or made the decision to step out of civilian life to join the fight on the frontline. Daria Svertilova finds purpose in creating a sincere and subtle portrait of her generation.

Her work goes on to explore the new reality of living in a time of war and how it is shaping her destiny and that of her companions. “I look around and I don’t recognise anything … I see a great resilience and bravery while the world around me is collapsing.”

The exhibition Generations of Resilience can be seen at Hangar gallery until 23 March 2024. Fiona Shields visited PhotoBrussels by invitation.