With its hidden doors, folding walls and clever optical tricks with mirrors and light-wells, Sir John Soane’s Museum feels like just the kind of place you might stumble across a portal to another dimension. Moving from one room to the next in this wildly reimagined London townhouse is never as straightforward as stepping through a simple doorway. The eponymous neoclassical architect and collector saw to it that the thresholds between the different parts of his house-museum were elaborate spaces in themselves, topped with lanterns and lined with mirrors and windows, offering views up, down and through his multi-levelled maze of antique treasures.

Step through one opening, expecting another stately drawing room, and you find yourself standing on a bridge, suspended in a three-storey “sepulchral chamber”, where a glazed dome brings light down to an Egyptian sarcophagus in the basement. Pull back the folding panels in the picture room, and you discover a statue of a nymph in a hidden recess, floating above a void that plunges into another sculpture-encrusted nook below the floor. Each carefully choreographed transition, each theatrical reveal, is designed to transport the visitor to a parallel universe, whether it be the ancient ruins of Giambattista Piranesi’s Paestum, the demonic halls of John Milton’s Pandemonium, or the drawings of imaginary cities made up of fragments of Soane’s own buildings.

Two hundred years later, Soane’s richly layered labyrinth has been extended with a whole new virtual dimension. Following a period of intensive research during the pandemic, experimental architectural duo Space Popular have unveiled the Portal Galleries, a beguiling immersive exhibition that explores the history and future of portals – a topic for which there could be no better setting. Using a combination of virtual reality films and physical exhibits, alongside drawings from the collection, the show charts the role of magical thresholds in fiction, film, television and gaming, and speculates on the fundamental role they will play in the coming virtual world.

“Portals are going to be everywhere,” says Fredrik Hellberg, co-founder of Space Popular with Lara Lesmes. “We are convinced they will be the main infrastructure of the rest of this century, just as ubiquitous as the car was to the last. To avoid future mistakes, we should start to get prepared now.”

The concept of virtual transport infrastructure might be quite a challenge to get your head around. But Hellberg and Lesmes are adamant that it is the next pressing design challenge, as our “scrolls become strolls”, and the internet takes on an ever more spatial dimension.

Think of the portal like the three-dimensional version of clicking on a link. Just as hyperlinks take you from one web page to another, portals are becoming the primary way to travel around the immersive internet (also known as the metaverse), taking you from one virtual space to the next. Who is designing these portals, they argue, and with what purpose in mind, will define how we all come to navigate the virtual world.

“They are very rudimentary at the moment,” says Lesmes, who spent much of the pandemic teaching with Hellberg in virtual environments, using social VR to meet with their students, who were often back home in different countries. “Someone ‘drops a portal’, and your avatars go through some kind of ring or frame together, but then there is often a black screen, or you have to close down the platform and find another app, and go through pages of links. It’s a horrific experience.”

Operating like time-travelling motorway engineers at the launch of the Model T Ford, Space Popular want to pre-empt the coming chaos of metaverse navigation by proposing a common civic infrastructure for virtual teleportation. “Portals will be the vessels to sail across the immersive internet,” they say in one of the films. “The way in which they operate will define the fairness of virtual environments and infrastructure.”

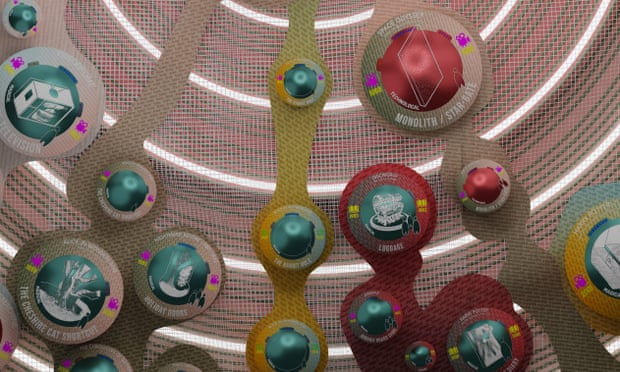

To imagine what form these vessels might take, the architects have mined the history of teleportation devices in fiction over the last 150 years, compiling a database of more than 900 examples, organised into 18 different categories. These are elegantly displayed on a multi-levelled table, upholstered with printed fabric, in the middle of one of the Soane galleries – in a similar manner to their information-rich printed carpet at the Riba – and explained in a couple of accompanying VR films.

The examples range from the rabbit-hole in Alice in Wonderland and the wardrobe in the Narnia books, to Dr Who’s Tardis, Back to the Future’s DeLorean and Platform 9¾ in Harry Potter, via all manner of holes, mirrors, cracks, bridges and “energy frames” found in sci-fi and fantasy fiction. Their timeline tells an eye-opening story, charting the explosion of portals after the second world war, marked by the likes of The Sentinel by Arthur C Clarke (which formed the basis of the film 2001: A Space Odyssey), the Wayback Machine in Peabody’s Improbable History, and the tollbooth from the 1961 book The Phantom Tollbooth, written by architect Norton Juster.

The following period, leading up to the cold war and the space race, saw portals take the form of massive energy-intensive machines and weapons built in the battle for world domination. They highlight the 1960s TV series The Time Tunnel, where thousands of people work under the desert surface on a secret megastructure, which would allow the US military to travel in time, noting how its iconic spiral design went on to inspire countless portals in future stories. The period after the cold war, meanwhile, saw portals serve more satirical and comical roles in lowbrow sci-fi and family movies – such as the phone booth in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, or the people-eating television in the 1980s body horror film Videodrome.

They found one of the most recurring types of portal to be the “portable hole”, first featured in the Looney Toons cartoon The Hole Idea in 1955, in which a scientist demonstrates his device for rescuing a baby from a safe, cheating at golf and escaping from housework. It later appears in the Beatles’ film Yellow Submarine, in the form of the Sea of Holes, as well as in Who Framed Roger Rabbit, reaching a hole-studded peak in the 1985 Marvel cartoon character, Spot – whose body is covered in portals.

For each of the 900 examples, they have catalogued how each portal works, where it leads, and who can use it, revealing that more recent examples often discriminate on grounds of class, status and ethnicity. In the Harry Potter franchise, for example, those who are born into a certain group can run through the wall into a future of power and privilege, while mere mortals smash their faces against the bricks.

While some of their charts and diagrams can be a little impenetrable, Space Popular’s overarching message is clear. As tech giants such as Facebook (now Meta) and Microsoft bid for domination of the metaverse, and the crypto community embraces it as a way to peddle further NFTs and flog virtual real estate, Lesmes and Hellberg are calling for a more equitable virtual future. “In the coming 15 years,” they write, “we must create a civic infrastructure for virtual teleportation that breaks with the discriminatory and opaque nature of locked doors, hidden vigilance, privacy breaches and concealed discrimination.”

They don’t pretend to have all the answers, but their mind-boggling archive of portals provides a hint of some of the directions the brave new virtual world might take. As they conclude in one of the films: “It is now the time to mind the doors we open, and to carefully consider the ones we close.” Personally, I’ll be taking the first flying phone booth out of the metaverse, and trying not to fall through one of the slippery holes to Zucker-land.