War, slave labour, concentration camps and life as a refugee: having survived such hardships, it is no wonder Yugoslavian musician Branko Mataja was happy to live quietly in a Los Angeles suburb and build custom guitars for the likes of Johnny Cash and Geddy Lee. His death in 2000 attracted no obituaries and his 1973 LP Traditional and Folk Songs of Yugoslavia remained unsung. Mataja had lived under the radar, a musician seemingly playing only for himself. Now, almost half a century later, his music is finally being reissued and it is causing quite a stir.

“What Branko did was unlike what anyone else was doing at the time,” says David Jerkovich, a 43-year-old American musician who is the force getting Mataja’s music heard. “His playing has this kind of outsider, intense quality and it’s just so unique to him. And his studio technique is incredible – he bounced and overdubbed sound in a manner no one else even approached.”

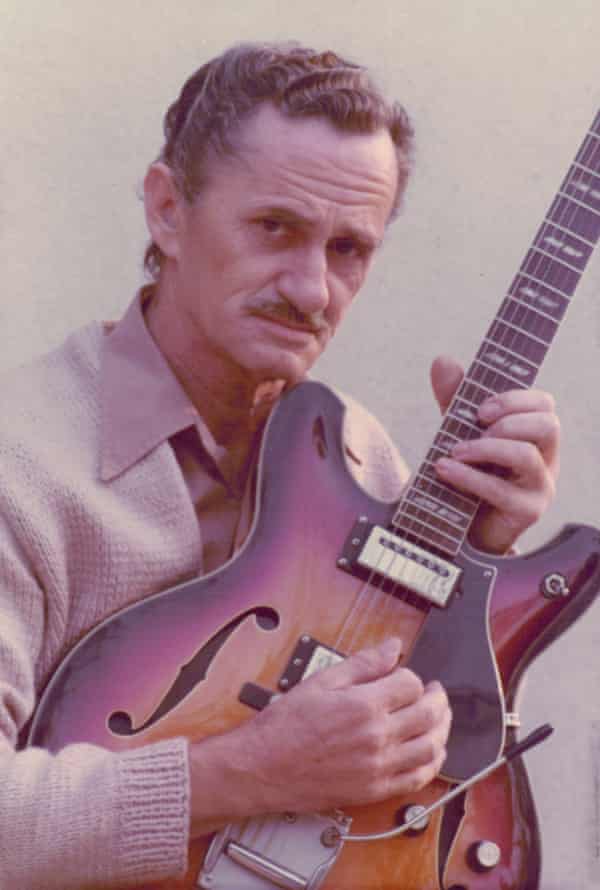

Jerkovich was cratedigging in a Hollywood used record store in 2005 when he came across a copy of Traditional and Folk Songs of Yugoslavia, priced at $7. “He just looked so badass on the cover that I had to buy it,” Jerkovich says. “I was buying Yugoslav-era music as my parents are from Croatia – I’m a first-generation American – and I was wanting to gain a greater understanding of their musical roots. I got home and put it on the stereo and …” He pauses, then says: “It’s unlike anything I’d ever heard before. What Branko has done is take these ancient melodies and built something very abstract, very beautiful, out of them.”

Traditional and Folk Songs of Yugoslavia was released on a tiny label; Jerkovich thinks it was likely a self-financed release. This and recordings Mataja issued on cassette a decade later are gathered on the new compilation Over Fields and Mountains, an album of sublime, spooky beauty: ambient electric guitar soundscapes that bear comparison to what John Fahey, Robbie Basho, John Renbourn and even Dick Dale achieved, having incorporated melodies and tunings from folk, blues, Indian and Arabic music. Jerkovich also emphasises that Mataja’s experiments with tape delay and overdub techniques are groundbreaking and akin to what Lee “Scratch” Perry and Brian Eno would later develop.

“He layered all these different sounds he was creating on a four-track recorder with remarkable skill and imagination,” notes Jerkovich. “I find Branko’s music a little psychedelic, even though I know that wasn’t his scene.”

Who, Jerkovich found himself asking, was this mysterious musician? Mataja (1923-2000) was born in the small coastal town of Bekar, then part of Dalmatia, now Croatia, before his family relocated to Belgrade. It was here 10-year-old Branko built his first guitar. During the second world war, Axis forces occupied Yugoslavia and the teenager was forcibly conscripted to Germany to work as slave labour. After American soldiers liberated the concentration camp he was held in, Branko hustled for the US army as a cook, barber, and pedlar of cigarettes, candy and nylons. He also played guitar in bars US soldiers frequented. Finding the US quota for refugees full and wary of returning to Yugoslavia, Mataja was accepted as a refugee by the UK: he initially lived in a displaced persons camp in Yorkshire. Here he met and married a Montenegrin refugee, Roksanda Radonjic. The Matajas became British citizens before emigrating to Canada in 1954, then in 1963 to Detroit, finally settling in Los Angeles in 1964. As long hair became fashionable and barbers struggled, Mataja was determined to focus on his first love: working on guitars.

He spent long hours in his workshop, and having taught himself electrical engineering and built a home studio he began recording himself. The only time he left his workshop for any amount of time was, apparently, to watch the World Cup. He had a son, Bata, who grew up to be a successful businessman supplying customised cars to the film industry. “Branko could be seen to have lived the proverbial American dream,” Jerkovich says.

“Dad loved to share his music,” says Bata. “If people came around the house he would play for them and they’d go ‘wow’. But what he played was popular songs of the 1940s – Nat King Cole, Django Reinhardt, that kind of music. I’m surprised he recorded these old Balkan songs because I don’t recall him playing such.”

Bata also admits to being surprised when Jerkovich and his friend Doug Mcgowan tracked him down and declared themselves enamoured with his late father’s music. Mcgowan works for Numero Group, a US specialist reissue label, but Bata refused his entreaties to license Branko’s recordings.

“Bata was busy with his own business,” says Jerkovich, “and didn’t see the point in us reissuing Branko’s music. He did give us what turned out to be Branko’s second album, Folk Songs of Serbia – which he had self-released on cassette in the mid-1980s and we had no idea of – and informed us about his father’s life, but it took 13 years before he finally came around.” Having retired, Bata finally relented and Jerkovich, who runs an LA recording studio, salvaged the now damaged master tapes.

It is unlikely we will ever understand why Mataja radically re-contextualised the songs of his childhood; he never returned to Yugoslavia and had no interest in the sectarian divisions that shattered the nation. “Maybe he was trying to connect with his mother,” Bata suggests; Jerkovich wonders if Mataja was trying to forge a sonic connection with a land he was torn away from as a teenager. The haunted atmospheres his music conjures allow for all kinds of interpretations.

Mataja was, says Bata, “very stubborn and determined, always experimenting, inventing things. And pretty intense.” Music was his father’s great love but, Bata observes, “he never thought of it as something that would make him wealthy. He just loved to make music. He was always inventing things and experimenting – he was like a mad scientist in his studio – and when he was playing guitar, he was in another world.”

Visitors to his workshop might be given an LP or cassette – that was the extent of his promo. Ill health forced Mataja to stop playing guitar in the 1990s, and, depressed, he died of a heart attack in 2000. He could easily have remained unknown had a young musician not paid $7 for Branko’s LP in a Hollywood used record store.

“Luckily they were persistent,” Bata says of Jerkovich and Mcgowan. “I now wish I’d done it earlier because when I hear people saying how much Dad’s music means – well, it’s very moving. I only wish Dad was alive so he could experience all the interest and enthusiasm. He told me ‘music is beautiful – it will open doors for you that you didn’t think will open’. And he was right!”