In 1959, Carlos Lyra’s musical partner and lyricist Ronaldo Bôscoli said that bossa nova is a state of mind. Lyra thought he was talking nonsense. “Today, I’m actually agreeing with him,” he reflects more than six decades later, while vividly narrating a flashback of the genre’s early days in 1950s Rio de Janeiro. “With our guitars and bottles of homemade drinks, we used to go to the beach at sunset and stay singing through the night. The next day, we would do it all over again. It was a joyous, carefree atmosphere.”

Lyra, who conjured that state of mind like few others with classics such as Você e Eu and Coisa Mais Linda, turned 90 last week and is one of the only musicians who helped birth the Brazilian genre still alive today. In April 1958, singer Elizete Cardoso recorded Canção do Amor Demais – the first album to present João Gilberto’s bossa nova guitar beat, inspired – mainly, but not only – by samba and American jazz. Less than a year later, Gilberto released the album Chega de Saudade, full of the beat he would later become world-famous for.

“We all started looking for new harmonies and ways to play samba, which is when João Gilberto appeared with that syncopated beat,” Lyra says, who had three compositions recorded by Gilberto on Chega de Saudade: Lobo Bobo, Saudade Fêz Um Samba and Maria Ninguém. The two artists had met a few years earlier, on the pavement opposite Copacabana’s Plaza hotel. Plaza’s bar was a regular destination for Lyra and Gilberto, who used to go there to appreciate the syncopated piano of Johnny Alf (one of bossa nova’s most important forerunners).

“Sitting in the back of the bar, in the dark, there was João, with his guitar and playing in a super strange way – his hands were placed in a crooked manner,” Lyra says, recalling their first encounter. Gilberto would then start turning up at his house: “When I arrived, I would find João in my pyjamas, on a mattress next to my bed, having tea with my mother.” They then lived in Mexico for a period. “João used to drive a Beetle and, when hitting the speed bumps, he shouted: “Viva Zapata!” He was a person who demanded attention and, if you didn’t watch yourself, you would be around him all the time. He always consulted me about the songs he heard and played – but he was also that person who called at midnight asking you to go out, and got furious if you didn’t go.”

Gilberto was obstinate, Lyra says, but inspirationally so. “He studied each song hundreds of times, syllable by syllable, so that it rang along with the harmony he was making. It was a goldsmith’s work, but once it was ready, it was a knockout.”

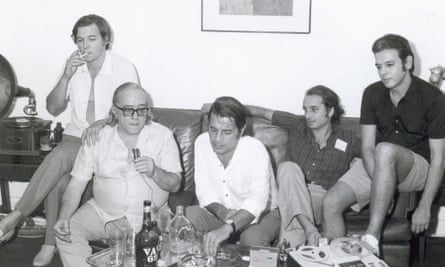

In their first gatherings in Ipanema and Copacabana, Lyra and young musicians such as Gilberto, Nara Leão, and Roberto Menescal (plus veterans such as Antônio Carlos Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes) could hardly have imagined they would gain international renown. “I only realised we were doing something worthy of attention when we performed in New York for our idols,” Lyra said, referring to the Bossa Nova night at Carnegie Hall in 1962, when Lyra and his peers played to Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Erroll Garner and other American jazz giants.

Before that, however, “we had no such thing as a goal that we wanted to achieve,” Lyra says. “We were young musicians from Rio’s middle class who, needy of a music expression we could relate to, started creating something closer to our realities.”

In the mid-50s, Rio’s radio stations no longer represented young musicians from Ipanema and Copacabana: they were dominated by samba-canção, a romantic genre marked by “lamentations, lovesickness and the drowning of one’s sorrows,” Lyra says (the Antônio Maria-penned Ninguém Me Ama is a good example, one of the genre’s most emblematic hits). The natural response, Lyra recalls, was to start “writing songs about our own reality: the beach, the sun, lovely girls and love stories.”

In the preface of Lyra’s book Eu e a Bossa (2008), Ruy Castro, author of renowned books on bossa nova, writes: “Without Carlinhos Lyra – as well as João Gilberto, Tom Jobim, and Vinicius de Moraes – bossa nova would not exist and we would still be singing Ninguém Me Ama.”

Even if it had existed without Lyra, Roberto Menescal says that without him, the genre would be lacking something important. At 85, Menescal, another bossa nova pioneer who composed O Barquinho and Você, is one of Lyra’s oldest music partners, having met in 1956 at a Copacabana high school. “We skipped the first day of class to play guitar at Lyra’s house. We found ourselves in full musical harmony,” Menescal recalls. So much so that, months later, they opened a guitar school together: “Everyone wanted to learn the so-called bossa nova beat. It was a fever.”

For Menescal, Lyra was the first person who expressed the newness in music that he was looking for, and did so with the most beautiful melodies. “When I first heard him play, I thought: ‘This is what I want.’ Lyra’s melodic lines go all the way up and then down – it’s pretty, even visually.” Jobim used to call Lyra the chief melodist of Bossa Nova, and Bruna Ramos da Fonte, a historian, musician, and author of Essa Tal de Bossa Nova, agrees: “When he chooses the notes, Lyra is meticulous. There’s no excess. It’s always a clear and refined melody.”

Lyra had already helped anticipate bossa nova’s lyrical content with 1955’s Menina, one of his first compositions. “At a time when the middle class and the elite were used to serious, ‘well-behaved’ lyrics, Menina established the change that Lyra’s generation looked for,” Ramos da Fonte says. “Girl, I’m no good for you,” go Lyra’s lyrics. “I’m a bad thing / Do you want them / To talk about you too / The way they talk about me?” Furthermore, Menina and its daring lyrics were first recorded in the voice of a woman, the singer Sylvia Telles.

Coupled with those colloquial lyrics, Lyra says that sophisticated harmonies and elaborate melodies are the other two key pillars beneath bossa nova, which he refuses to define as a rhythm. Instead, it is “a way of composing – but people don’t accept it as such because bossa nova [as a rhythm] ended up becoming a strong brand.” American standards, French chanson, Mexican boleros, Debussy’s impressionism, the Brazilian samba of Noel Rosa, and, Lyra recalls, “the Cuban albums my dad used to bring from his work trips” have all inspired his creative process since.

In 1961, along with other young artists and intellectuals, Lyra founded the Popular Center of Culture of the National Union of Students. The “CPC da UNE” as it was called, was a left-leaning initiative aimed at breaking social class walls through arts. As its music director, Lyra wanted to bring bossa nova closer to working-class people, and working-class culture (including the samba of Nelson Cavaquinho and Zé Keti) closer to the middle class.

“I started to realise the importance of lyrics that delivered a social message,” Lyra says. Disturbed by how “we, middle-class youngsters, lived in a bubble”, he stepped away from bossa nova that was disconnected from social issues. “After I joined the political movement, my lyrics gained new layers. What I do, until this day, is bossa nova, but neither my lyrics nor myself are alienated.”

After composing songs of socio-political relevance, such as Influência do Jazz (an ironic criticism of the excessive American jazz influence on samba) and Maria Moita (on class and gender inequalities that have formed Brazil), he lived outside Brazil for 10 years after the military dictatorship took over the country in 1964. “I engaged in the struggle for social justice. This forced me to self-exile, but, at the same time, made me stronger and more creative,” Lyra, who moved to the US and Mexico, affirms. In Mexico, he even founded a group inspired by CPC da UNE.

With a life so intertwined with the history of bossa nova and Brazil itself, Lyra turns 90 with a feeling of satisfaction. “I’ve always pursued quality music, but I don’t make intellectual compositions,” he says. “Quality music is that which comes from the heart.”