We heard a rumor that some of you have been feeling a bit too comfortable of late. That’s unacceptable. Paranoia is the only option, so we must provoke some with a troubling question: Have you considered that the government may be secretly experimenting on you? It’s happened to people before. Consider the sad cases of…

Radiation Vertus

In 1927, Gibson County Hospital in Indiana was having money problems. The head physician figured they could solve them through the burgeoning field of radiation. They could irradiate some people, and if this produced any interesting results, the hospital would become rich and famous. If it didn’t, no worries.

This physician’s brother-in-law was a school trustee, so the hospital found themselves a fine source of unwitting volunteers: Ten Black children at the Lyles Consolidated School. They told the kids alternately that they were going on a field trip and that they were receiving treatment for ringworm (a fungal infection that’s easily cured by home remedies such as iodine). At the hospital, they plopped a device on each kid’s head and delivered a full-body radiation dose via the skull.

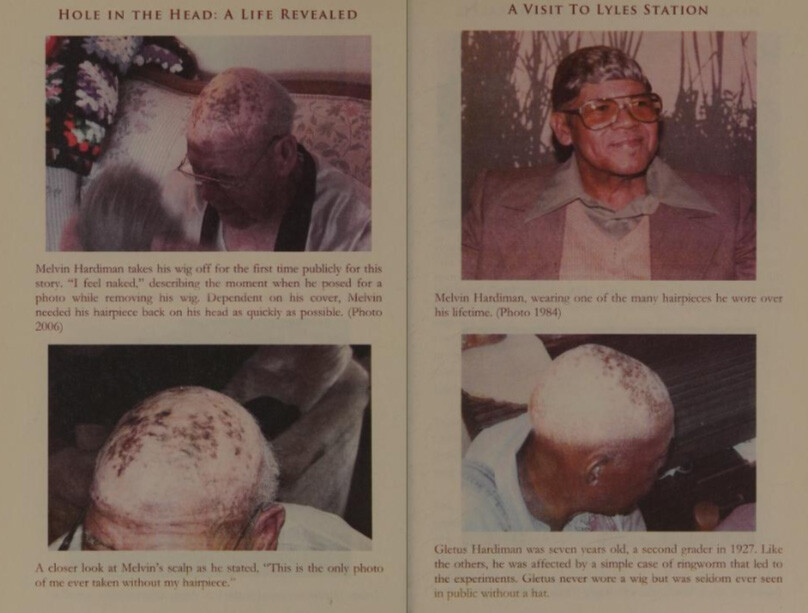

The kids were soon all vomiting and shooting out diarrhea. Their chaperone, only now realizing the doctors were doing something horrible, herded the students into the school bus to take them to get help — only to realize that if they needed medical care, they actually already were at the hospital. The kids would grow up and spend the rest of their lives with bald and discolored scalps…

Uplift Productions

…but the experiment hit each child with a higher radiation dose than the kid before them. The final child was five-year-old Vertus Hardiman. The way he’d later recall it, when the nurses plunked the device on his head and turned the dial, one yelled, “Oh my God. I’ve given him too much.”

The blast left Vertus with a head wound, one that never healed, not for the next 80 years of his life. It began as an ulcerated sore then progressed to a cancer that — though it never reached his brain — caused the top of his skull to collapse. He wore a wig his whole life, and a beanie on top of that, successfully hiding the hole in his head. You can get a look at it two and a half minutes into the video below (which, for the first couple minutes, seems like a documentary about the Depression-era South, featuring no unhealing head wounds at all).

The parents of these kids took the hospital to court, but the hospital emerged from the trial unscathed, as the parents had all signed permission slips for the visit. So, be careful what you sign the next time your kid’s off to a field trip. There’s always the chance the slip says something like, “This trip consists of a visit to a museum, followed by euthanasia.”

Plutonium Al

Quite a few people found themselves unwitting subjects in radiation experiments in the years that followed. In the 1950s and 1960s, a bunch of hospitals injected patients with plutonium, polonium and uranium, to measure how long it took their bodies to chuck the stuff out. Doctors generally sought out cancer patients for these experiments, for two reasons. One, the hospital would pretend this was a cancer treatment (we’d later develop radiotherapy for cancer, but injecting radioactive metal isn’t how you do it). Two, if the radioactivity killed the patient, it didn’t matter, since they were terminal anyway.

One subject of these experiments was a house painter named Al Stevens. He had stomach cancer, the doctors figured. But a little bit into the experiment, they discovered he actually never did. They kept the experiment going anyway. They did not tell Al they were injecting him with plutonium, and to keep up the ruse, they also continued to tell him he had cancer.

To test how his body was dealing with the plutonium, they periodically collected urine and stool samples and also extracted some slices of rib and spleen. Thanks to the continuous radiation that internal plutonium was pumping out, he was later nicknamed “The Most Radioactive Human Ever.” The radiation, though, doesn’t seem to have cut his life short. He lived to be almost 80, when he died of heart disease.

Cell Line John

Our next guinea pig also wound up with some spleen grabbed for research, and unlike Stevens, he really did have cancer. The man was named John Moore, and the consent form he signed, when he was receiving treatment for leukemia, read: “I voluntarily grant to the University of California all rights I, or my heirs, may have in any cell line… obtained from me.”

UCLA had yanked his spleen out to stop the cancer growth, and this worked for a while. They also noticed something wondrous about this spleen. The T cells in them cranked out a kind of signaling protein more efficiently than they’d ever thought possible. They dragged Moore in for a few additional visits, in which they extracted his bone marrow — not to treat any illness but simply because they wanted it. They soon had enough T cells that they could culture them and keep them alive and reproducing for years, manufacturing all the lymphokine proteins they wanted.

When Moore found out the truth, he sued and lost. The doctors had the right to hold on to those cells as long as they wanted and do whatever they wanted with them. It’s scary because while Moore argued that the cells were his, one might also argue that the cells were him. If you’re inclined to say, “No, only my brain is me, not my marrow,” that’s just your brain talking, and your brain is clearly biased in this matter.

Sarin-Gas Ron

Ronald Maddison knew he was participating in some sort of experiment. As far as he knew, he and the other RAF volunteers were signing up to receive an unproven cure for the common cold. He certainly didn’t think the experiment was going to kill him. We know this because he planned to use the payment to buy an engagement ring.

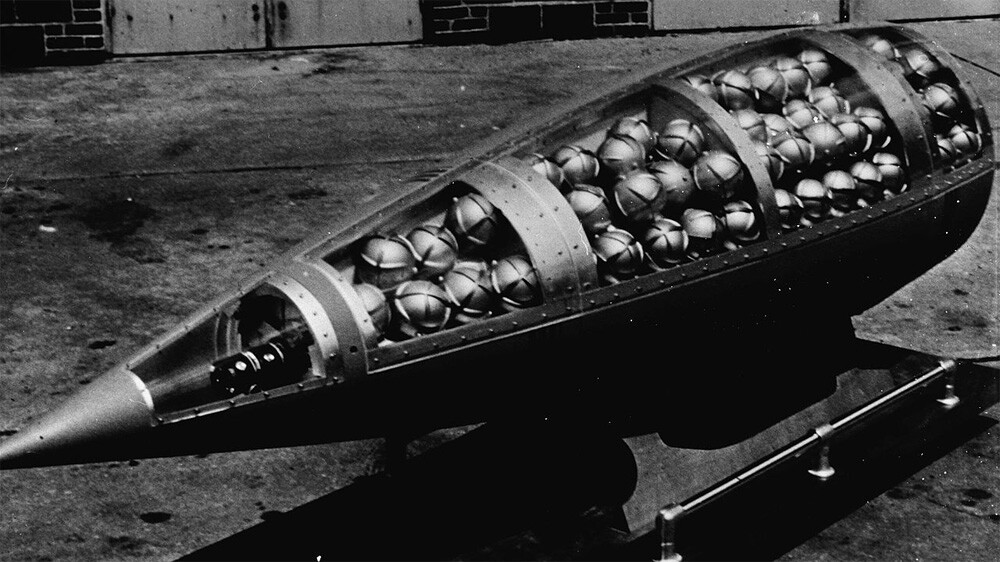

The government was actually testing sarin gas on him. The year was 1953, and Britain was curious exactly what dose of sarin is lethal on humans, and the best way to determine this was to send a bunch of volunteers into a gas chamber. They all wore respirators, and researchers poured 200 milligrams of sarin onto a cloth tied to each guy’s forearm. Maddison didn’t last the planned 30 minutes in the chamber. He came out, said he’d turned deaf and then lost consciousness. Adrenaline injected into his heart couldn’t revive him.

This was all kept secret at the time. The military forbade Maddison’s family from describing what little they knew and sealed the body in a steel coffin to prevent observation. The government did offer the family some compensation, however. They paid them £20 so they could buy a funeral suit (no one saw this suit, because of the sealed coffin). They also paid the family £4 to buy refreshments for the funeral.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.