While Elvis Presley was an American icon, the rest of the world worshipped him too.

But Presley never experienced that global adulation in person. His manager Colonel Tom Parker, born in the Netherlands and residing illegally in the U.S., did not have a passport, which ultimately kept Presley from taking his wildly successful touring act of the early 1970s overseas.

“The Colonel couldn’t go and he didn’t trust anybody enough to take him over there,” said author Alanna Nash, who wrote Parker’s biography. “He was always afraid someone was going to steal Elvis from him.”

In 1972, Parker found a way to satisfy the pent-up demand of the worldwide audience — a live TV concert delivered to international broadcasters via satellite. He is said to have been inspired by the live TV images from China that viewers saw during President Nixon’s historic 1972 visit.

On Friday, RCA Records releases a newly remastered version of that January 1973 show — “Elvis Aloha From Hawaii via Satellite” on CD, vinyl, digital download and a Blu-ray video disc — in honor of its 50th anniversary. It’s a throwback to a pop-culture landmark and an opportunity for younger fans who became acquainted with the King through Baz Luhrmann‘s Oscar-nominated “Elvis” to experience what turned out to be the final triumph of his career.

While not as heralded as the 1968 NBC show known as “The ’68 Comeback Special,” which thrust Presley back into the contemporary music scene after a lull while he made movies, “Aloha” stands as the last recorded live performance of Presley at the peak of his powers before the downward spiral that ended with his death on Aug. 16, 1977.

“It’s really his last big hurrah,” Nash said.

There was a bit of bluster in the promotion of the event, with claims by Parker and RCA that it reached an audience of 1 billion people. Still, Presley was the first artist to carry a satellite broadcast on his own (in 1967 the BBC aired “Our World,” a program that included multiple acts including the Beatles).

Presley’s concert, held Jan. 14, 1973, at the Honolulu International Center Arena, aired live only in Asia and Oceania. It was seen in Europe the following day and did not show up in the U.S. on NBC until April 4, 1973, where it was watched by a staggering 57% of homes using television that night, according to Nielsen.

(Executives at MGM begged for the delayed U.S. broadcast as they feared it would cannibalize the moviegoing audience for “Elvis on Tour,” a documentary that was still in theaters. The concert date also conflicted with the Super Bowl.)

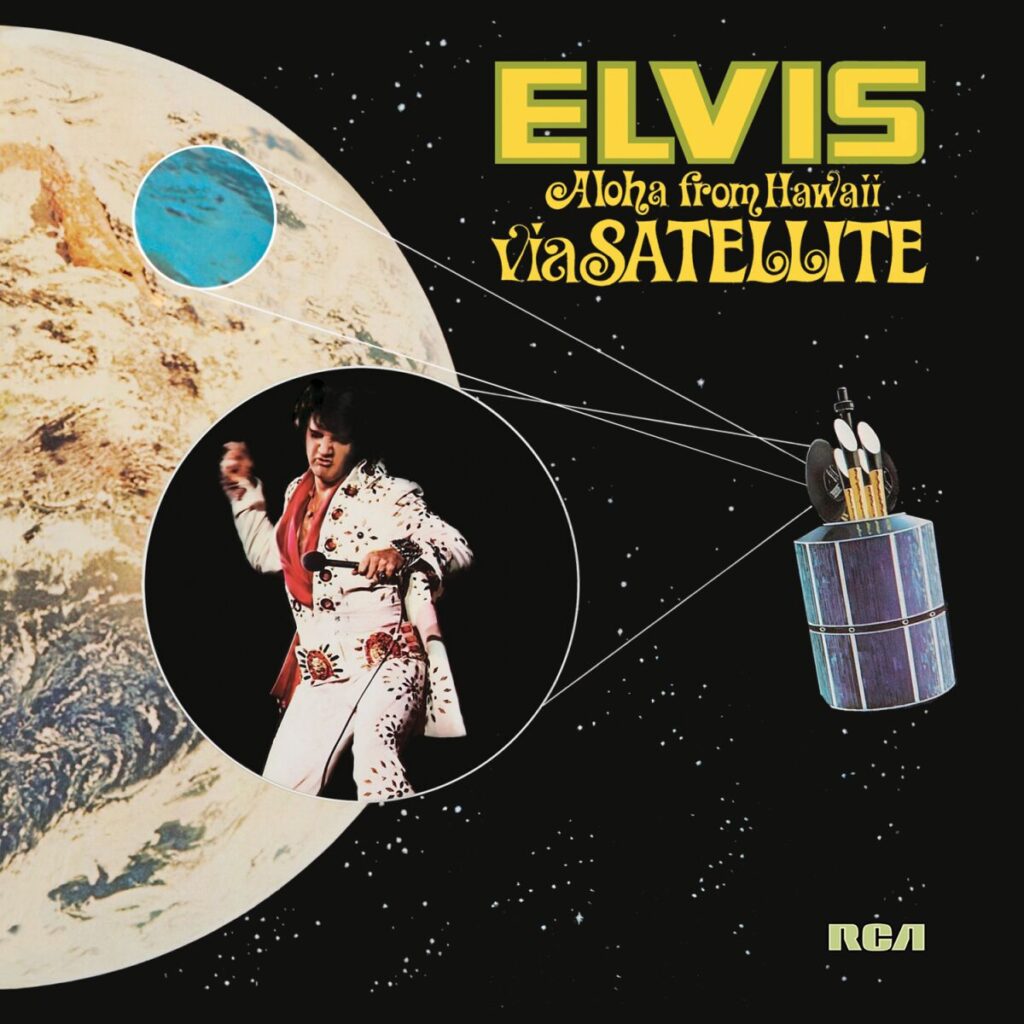

The album cover for “Elvis Aloha From Hawaii via Satellite.”

(RCA Records)

The concert came at a time of personal turmoil for Presley. His marriage to Priscilla Presley was over and his dependence on drugs was deepening. One reason Parker proposed the concert was to get the King out of his funk.

NBC, under the same corporate ownership as RCA Records at the time, hired veteran producer Marty Pasetta to oversee the show. As preparation, Pasetta attended a Presley concert in Long Beach. He was not impressed; Presley was pale and puffy and his onstage movements were limited.

Pasetta knew how to handle big stars. He was a seasoned master at managing big events for the small screen, having produced Oscar telecasts and presidential inaugurations. Still, he was a bit unnerved at having to confront Presley, who was accompanied by two pistol-toting bodyguards at their first meeting at the Hilton Hotel in Las Vegas.

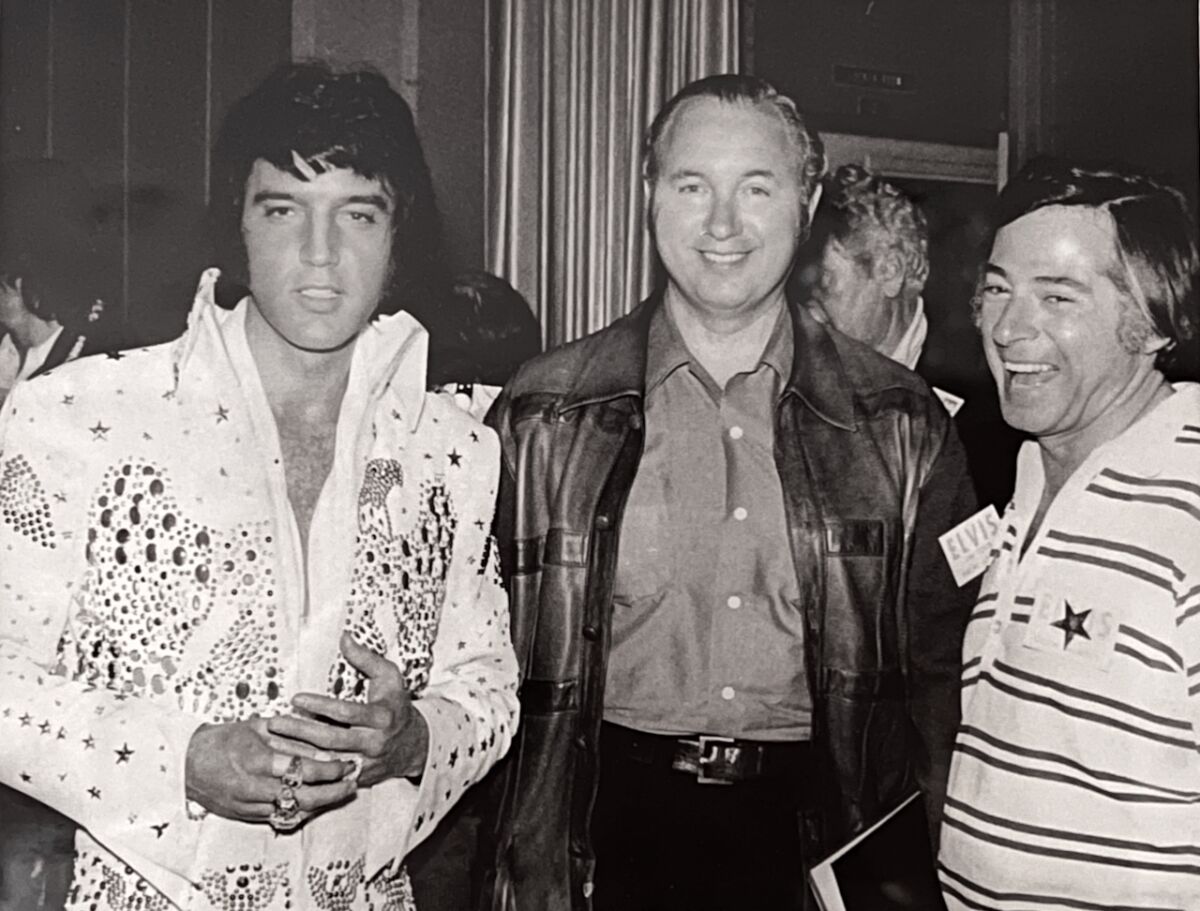

Elvis Presley, left, NBC executive Tom Sarnoff and producer Martin Pasetta in Honolulu on Jan. 14, 1973.

(Elise Pasetta)

“Marty told him, ‘You’ve got to lose weight — you’ve got to move more,’” Pasetta’s widow, Elise, recalled in a recent phone interview. “Elvis had his dark glasses on. He threw them off and he came over and hugged Marty and said, ‘You’re the first person that ever told me the truth.’”

Presley went on a crash diet, aided by injections of urine from a pregnant woman, in which he was limited to 500 calories a day of dried food. By the date of the show, he looked tan, rested and ready, a sleek figure in his bejeweled white jumpsuit and cape, although Nash noted he still needed an amphetamine-infused B-12 injection before going on.

Presley also caused a slight panic with his wardrobe handlers as he gave away the ruby-encrusted belt of his costume to the wife of “Hawaii Five-0” star Jack Lord, whom he met at a rehearsal. A new one had to be made and shipped in time for the show.

Pasetta sold Presley on a set design that included a lower stage and a long runway that allowed the star to get closer to female fans, who put leis around Elvis’ neck during the performance. They got a kiss, a scarf or a perspiration-filled hankie in return, keeping the crowd in a frenzy for the full hour.

Above the stage, “Elvis” was spelled out in different alphabets, and there were flashing lights that presented an image of him swiveling with a guitar.

In Japan, anticipation of the show was so intense, the broadcast showed the Hawaii audience filing into the auditorium for more than an hour before the concert began, Elise Pasetta recalled.

The music in “Aloha” is representative of Presley’s touring show of the era — he had been on the road during much of 1972 — and his personal taste at the time. Some of the performances of rock ’n’ roll classics — his own and covers such as “Johnny B. Goode” — feel a bit obligatory, perhaps a sign that he had outgrown the music of his youth.

Presley is far more emotionally involved in the show’s heavily orchestrated ballads, such as “My Way,” “What Now My Love,” “It’s Over” and “You Gave Me a Mountain,” which were more in the ilk of middle-of-the-road pop singers Tom Jones or Engelbert Humperdinck. The drama is turned up to 11 on “An American Trilogy,” the Mickey Newbury-arranged medley of “Dixie,” “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and “All My Trials” that became a staple of Presley’s live show at a time when the country was weary of the Vietnam war.

Ernst Jorgensen, producer of the “Aloha” reissue and keeper of the Presley catalog for more than 30 years, acknowledged that the era is not a favorite among rock purists and critics. (“He strays into Caesar’s Palace territory,” Jon Landau wrote in Rolling Stone.)

“At that time, there was so many people who still wanted him to be rock ’n’ roll,” Jorgensen said. “He matured as an artist, and not necessarily the way that the rock generation thought you should mature.”

There are moments throughout the show that display Presley’s stylistic prowess, especially on “Steamroller Blues,” a song from James Taylor’s “Sweet Baby James” album that mocked the white boy blues bands of the 1960s.

Presley delivers it with a sly smile, showing he gets the joke. Even with its absurd lyrics (“I’m a napalm bomb, guaranteed to blow your mind”), he makes the song feel authentic. It became a top-20 single.

“Elvis was at his very core a blues singer,” said Nash. “It becomes an entirely different kind of song from Elvis.”

While Presley’s live show was a well-oiled machine by this point, Jorgensen sensed a slight nervousness on the singer’s part on the program.

“He might have been somewhat overwhelmed by the event,” he said. “And the musicians say later that it didn’t really dawn on them until after the show that they’d been part of music history.”

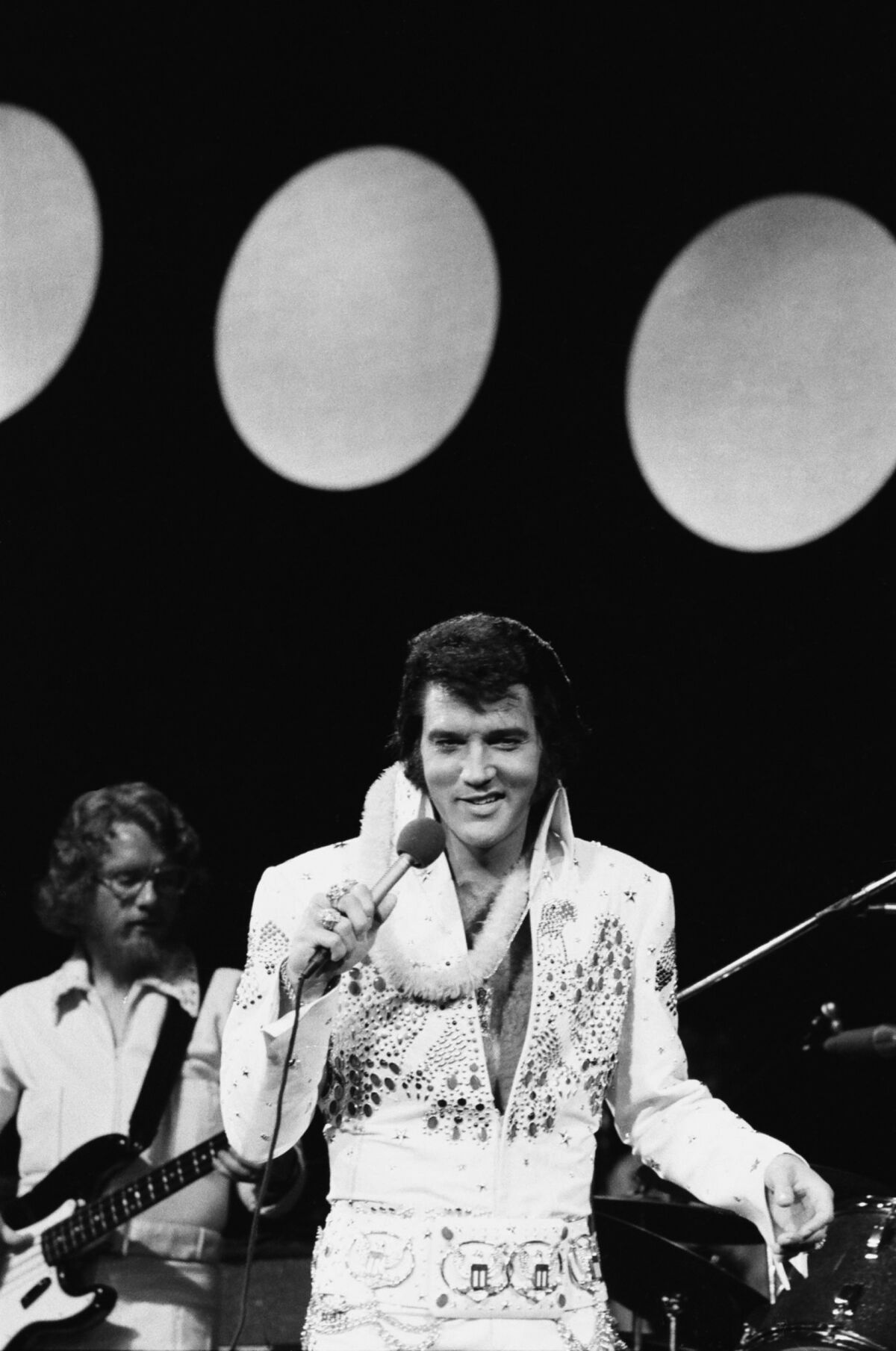

Elvis Presley performing in Honolulu on Jan. 14, 1973.

(RCA Records)

The concert and telecast went off without a hitch. Elise Pasetta, who was backstage at the show, remembers seeing a jubilant Presley afterward. “He came walking very quickly over to me, picks me up and spins me around and said that ‘this the best time I’ve ever had,’” she said.

The double-album soundtrack of “Elvis Aloha From Hawaii via Satellite” was rushed into stores on Feb. 4, 1973, three weeks after the concert and only seven months after RCA put out Presley’s “Elvis as Recorded Live at Madison Square Garden.”

The album jacket for “Aloha” — with its illustration of a satellite beaming an image of Presley to Earth — had to be printed before the concert, without a listing of track titles. A sticker with the set list was affixed to the cover after the vinyl was pressed.

“Aloha” steadily climbed the Billboard 200 chart and hit No. 1 in early May, sales propelled by the concert’s airing on NBC. It marked Presley’s first time on top of the album chart since 1964 and went on to sell more than 5 million copies in the U.S., further validating the career transformation that began with his comeback special.

“You see in ‘Aloha,’ even more than the ‘Comeback Special,’ a real hunger to prove that he is a relevant artist, that he has survived the psychedelic period and has come back into his own,” Nash said.

Jorgensen is pleased that the reissue presented the opportunity to remaster the recording, which he felt sounded compressed and “a bit lackluster.” Matt Ross-Spang, a Grammy-winning Memphis-based audio engineer, went to work on it, bringing out more clarity in Presley’s voice.

The new “Aloha” will satisfy Presley completists, as it includes a recording of the dress rehearsal and tracks recorded after the show used to fill out the 90-minute version of the U.S. telecast.

There appears to be no end to the reservoir of Presley content. On Aug. 15, streaming platform Paramount+ debuts a new documentary, “Reinventing Elvis: The ’68 Comeback Special,” which explores the backstory of the groundbreaking show. Director Sofia Coppola’s “Priscilla,” a theatrical film telling the story of Presley’s marriage, is scheduled for release in October.

But the line may be drawn at Presley’s final TV special, which aired on CBS less than two months after his death (a poignant performance of “Unchained Melody” on the program is re-created in Lurhmann’s “Elvis” and uses a brief clip of the actual footage shot in June 1977, when Presley appeared overweight and clearly in poor health). The entire show has never been given an authorized video release.

“There’s no decision made on that,” Jorgensen said. “There’s been various speculations on how Lisa Marie (Presley’s daughter, who died in January) felt about it and I don’t know if that has opened up for a discussion now. It was just total heartbreak.”