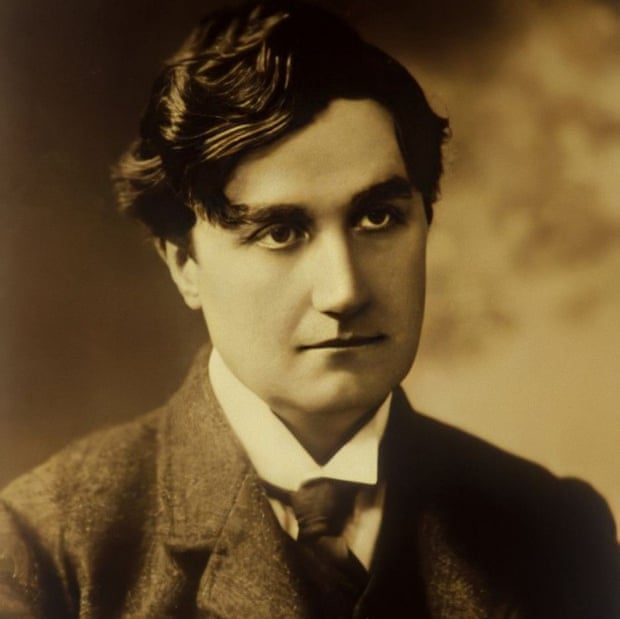

Ask people about Ralph Vaughan Williams, whose 150th anniversary we celebrate this year, and you might be told either that he is hands down Britain’s favourite composer or a parochial embarrassment whose music sounds like “a cow looking over a gate” (to quote one critic). Both judgements are usually based on just two pieces: Fantasia on a theme by Thomas Tallis and The Lark Ascending, which have appeared at or near the top of the Classic FM Hall of Fame poll for 20 years. In 1958, in the last year of his life, he was unquestionably the grand old man of English music, yet his last major work, the ninth symphony – to my mind a masterpiece – was written off by many critics as old hat.

Vaughan Williams, whose 150th anniversary we celebrate this year, has always been in and out of fashion. Many listeners have an “a-ha” moment, whether it be one of enlightenment or rejection. Mine, the former, took place listening to his fifth symphony. Written during the dark days of 1942, it left its audience speechless, tearful and grateful for its message of peace and hope. But I knew none of this when, a blank-slate teenager, I put needle to LP and within seconds – a low drone in the strings, two visionary horns, some dreamy violins – I was hooked. That will not make much sense unless you have heard it. So, take a moment out of your busy day. If the symphony’s first minute is not your thing, listen to the very last, a wordless alleluia the like of which is heard at the gates of heaven. If you are still not charmed, keep reading. There are many sides to Vaughan Williams, as I quickly found.

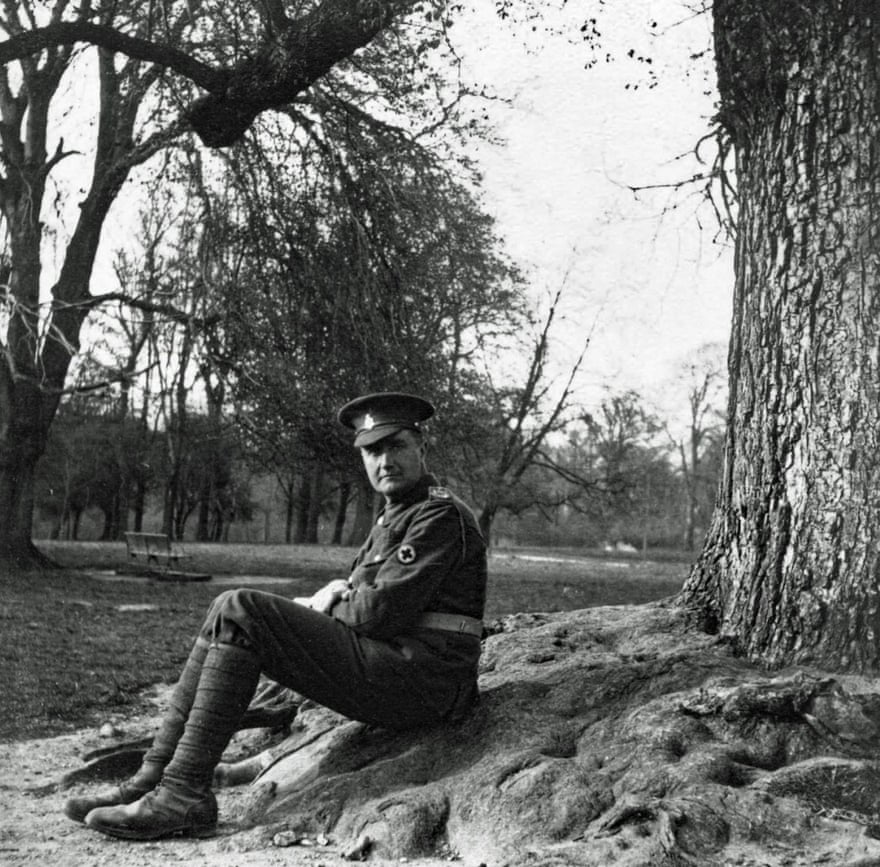

The course of my love did not run smooth. I grew impatient with the Pastoral Symphony (no 3), staring into the vacant eyes of that cow, and then I ran away scared from the fourth Symphony which assaulted my tender ears. I hear both differently now. The Pastoral is a requiem for the young men lost in the first world war, some of them friends and students of the composer. It was conceived on long, quiet evenings in northern France as the sun set over the battlefields where Vaughan Williams served as an ambulance driver. He witnessed things, as so many did, that he was never to speak of, except perhaps in music. The fourth symphony I now hear as a post-war expression of rage, dissonant from first to last, a hellish gate that might appeal to my previously unimpressed reader.

Vaughan Williams was slow to find his own musical voice. In his student days, England still looked to Germany for its musical models – Mendelssohn and Brahms – so he was the despair of his harmony professor when sample minuets came out modal. (Think Fred Astaire in clogs.) From his late 30s, however, he evolved into a one-man musical institution. He edited Anglican hymnbook The English Hymnal, cycled around country pubs collecting folk songs, was active in the English Folk Dance Society, though himself something of a galumpher, and conducted amateur choirs and professional orchestras with passion and the occasional burst of temper. As the second world war neared its end, he was the one authorities turned to for “A Song of Thanksgiving”, to be ready for VE Day. And he was a beloved teacher who supported young composers financially and in other practical ways. He once had to bring to heel an orchestra which was openly laughing at a young, then unknown Benjamin Britten. Perhaps most importantly, he set up what is now the RVW Charitable Trust which still distributes his royalties to fund new works. Never having had children of his own, these beneficiaries are in effect his musical heirs.

English through and through, Vaughan Williams was steeped in his country’s literature and art, old and new. He set words of Housman and Kipling, Shakespeare (try the Serenade to Music from The Merchant of Venice) and Herbert (Five Mystical Songs’s Love bade me welcome – you will thank me!), and there is an opera on Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. The closing scene of HG Wells’s Tono-Bungay inspired the atmospheric end of A London Symphony (“Light after light goes down … London passes – England passes”) and that “old hat” ninth symphony was sparked by Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles. You can even hear the eight o’clock chimes marking the moment of Tess’s execution.

The scenario and music of Job, a Masque for dancing (not a ballet – he disliked “over-developed calves”) were based closely on William Blake’s illustrations to the Book of Job, and the hall-of-famous Tallis Fantasia is gothic architecture in music. Vaughan Williams confessed that he himself sometimes did not know whether he had composed a piece or merely remembered it. He likened the process to seeing Stonehenge, New York or Niagara Falls for the first time: it was as if he already knew them. The Tallis Fantasia sounds as if the musicians are reading not sheet music but runes carved on rock.

For some, however, Vaughan Williams’s very Englishness can be a barrier to appreciation. I have been lucky enough to perform his music outside the UK and see how it touches and speaks to musicians and audiences who know nothing of its cultural roots. The most common reaction to hearing one of the symphonies is a sort of bemused appetite for more: how many of these are there? Why didn’t we know them already? And I owe Vaughan Williams a debt of thanks. Ten years ago the North German Radio Philharmonic asked me to become its chief conductor as a direct result of a performance of the sixth symphony – a devastating piece completed soon after the second world war. Listen to its post-apocalypse ending, 10 minutes of all but silent, static music (and spare a thought for the orchestras that play this shatteringly difficult piece).

Cultural roots lie deep and old. Dig deep enough, as Vaughan Williams did, and you find the roots of music entangled, shared even with other cultures, on a bedrock of pentatonics, ancient modes, hymns, chorales and folk dance. Perhaps for that reason Vaughan Williams had so much respect for Sibelius, the great Finnish composer to whom he dedicated that marvellous fifth symphony “without permission”. Their music sounds and feels totally different but they were both mining the same deep cultural seam. And it is for that reason that I believe Vaughan Williams’s music has lasted in our estimation and will for a long time, though fashions come and go. Calling the ninth symphony “old hat” was intended as an insult. I hear the piece however as the summation of a life’s work, tired-sounding perhaps but deservedly so after such long, rich creativity.