Ever since the first Garfield strip in 1978, Jon Arbuckle has been kind of a loser. His human friends are nearly nonexistent, and until finally nabbing Liz (Garfield’s vet) in 2006, he was constantly getting rejected by women. Not to mention his dreadful sense of fashion and spending what even the most adamant of cat people would call an excessive amount of time talking to his famous feline. But what if Arbuckle didn’t even have the cat? What if he was just talking to thin air? That question stuck in the brain of Dan Walsh, a technology manager from Dublin who popularized the viral hit Garfield Minus Garfield.

Launching on February 13, 2008, Garfield Minus Garfield was an internet comic that deleted the titular tubby tabby from carefully selected Garfield strips, leaving Jon talking to an empty void. The result was a lonely man made even lonelier. Without Garfield to keep him company, Jon seemed to be going through an existential crisis and grappling with suicidal tendencies. A depression meme before depression memes were a thing, it quickly took the internet by storm. By that summer it had been covered in the Washington Post and New York Times, with Paws Inc. (Garfield’s then parent company) agreeing to do an official book of Garfield-less Garfield strips.

While Walsh released daily strips in the early days of the comic, he now just does a few a year. However, he still enjoys delving into the psyche of Jon Arbuckle and was happy to speak with us about his love for Garfield, Garfield Minus Garfield’s origins and precisely why Jon’s fragility is so compelling.

Creating ‘Garfield Minus Garfield’

I was a kid in the 1980s, and here in Ireland, we had those strangely shaped books of the Garfield comic strips. There were a bunch of those around the house. Back then, very little of that kind of American media, like comic strips and comic books, made its way to Dublin. But Garfield did, and I obsessively read those books over and over. So, I’d always been a fan of Garfield.

Garfield Minus Garfield began on a message board that, I think, went all the way back to 2006. I’m racking my brain trying to remember its name, but it was the beginning of people screwing around with the Garfield format.

There were about 12 strips where this anonymous person had stripped Garfield from Garfield strips. They’d posted them to this message board, and then the same 12 strips suddenly sparked up everywhere. Somebody even put them up on a website but then took them down, probably from fear of violating some copyright.

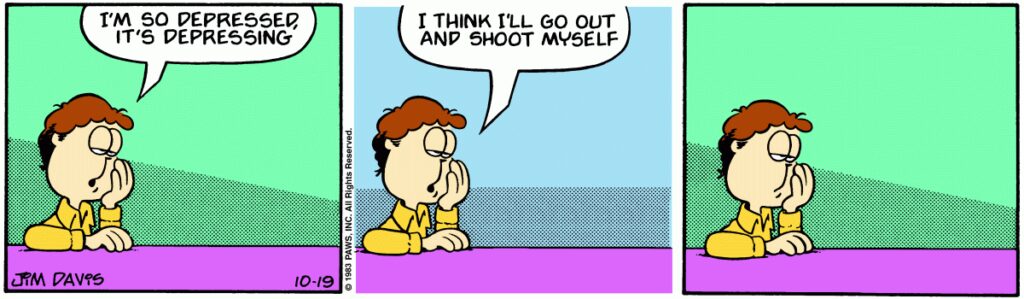

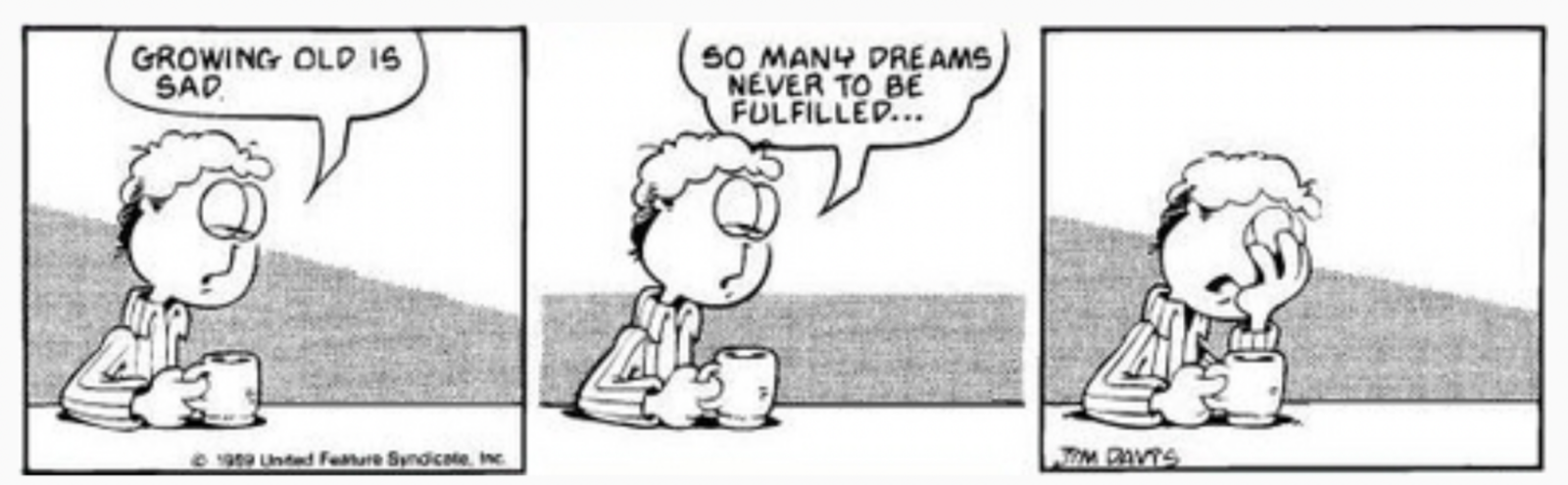

When I saw them on that message board, I quickly became obsessed with the idea of it. I was astonished at how horrifically dark they could be. It suddenly became a very depressing strip about a very depressed man. The example I always use is one with Jon saying, “I’m so depressed it’s depressing.” Then, in the second panel, he actually said this in a children’s comic: “I’m going to go outside and shoot myself.” The third panel obviously had Garfield say something to take the edge off, but in Garfield Minus Garfield, that panel was empty.

The trick of Garfield Minus Garfield was to leave Jon’s words unchanged, so even in the original Garfield comics, that darkness was always there; Garfield Minus Garfield just helped to bring it out.

After discovering these comics, I went into the archives and started looking for strips that really highlighted Jon’s depression. That was my addition to the meme — that I went back into the archives and made a website to put them up, which I didn’t take down.

I never did find out who did those original 12 strips, and, believe me, I searched for them. However, I did hear from the guy who put up that website for a little while there. He was really angry. I said to him, “Tell me your name, and I’ll put it on the website and say that you were the first one to publish a website. But then he never came back to me again. I think he was more angry with himself than he was with me because he took down that initial website. I’ve always tried to be open about the fact that I didn’t originate the idea.

‘Garfield Minus Garfield’ Takes Off

When I put them up on the website, I did it daily. Then I sent them to maybe 10 friends. There was a site then called StumbleUpon, which was basically internet roulette: You’d put in your interests, hit the “Go” button and be presented with a handful of websites. I submitted garfieldminusgarfield.net to StumbleUpon and Digg, and the volume of traffic from those sites was astonishing. I was using this analytics package to find out how many people were visiting, and within two weeks, I was getting 800,000 visits a day. It was so much that the analytics site I was using emailed me, saying, “I’m sorry, we need to kick you off because you’re getting so much traffic that our real-time analytics are running two hours behind for everyone.” I completely screwed up their enterprise. That kind of traffic, which leveled out to about half a million per day, went on for months.

When I saw half a million people, though, I lost my nerve. I panicked because I was afraid I was going to get sued. The site was done through Tumblr, and it was the biggest thing on there. I got so scared that I reached out to Tumblr’s founders, David Karp and Marco Arment, who really supported me. They told me, “Look, this is the most popular thing on Tumblr at the moment. You’re doing really good work, and you’re getting lots of people to the platform. Keep it up, and we’ll protect your anonymity. We won’t tell anyone who you are.” That gave me the courage to keep it up, and I kept putting up a new strip every day.

I remained anonymous for a while and soon began getting interview requests from these big U.S. publications. I think it was the Washington Post that reached out and asked to do an interview. I said, “Yeah, okay, but I want to remain anonymous,” and they said, “No problem.” I talked to them, and this really charming lady asked me my name, and I said, “I’m Dan Walsh from Dublin, but I want to remain anonymous.” She said, “No problem at all.” Three days later, the Washington Post article said, “Dan Walsh, Garfield Minus Garfield” — she completely exposed me.

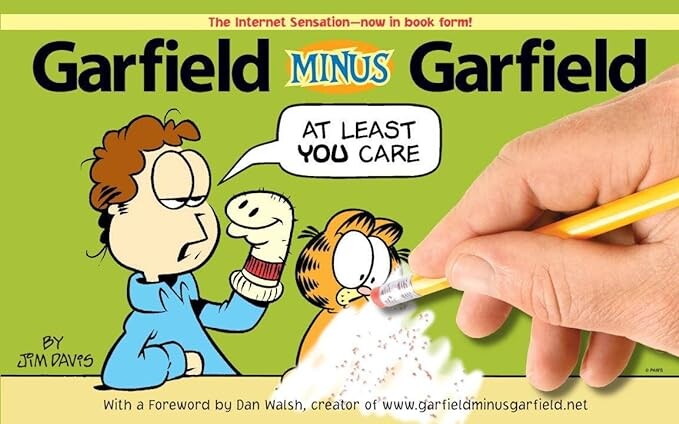

At the time, I was working in IT in a corporate pharmaceutical job, and not long after that article was published, I got this call. A woman was on the phone, and she said, “Hi Dan, this is so-and-so from Paws Incorporated — don’t panic.” I immediately panicked. I just thought, “Oh shit, what’s going to happen?” Then she said, “Look, we love what you’re doing; we don’t want you to stop. Keep the site. We’d like you to help us with a book we’re going to make.” Basically, the deal was: I keep the website, and they keep the book. They also asked me to add a link to the original strips, but that was it. They were super cool about it. I was amazed at how cool Jim Davis and all of those people were. They were incredibly supportive and nice. It was very liberating. I didn’t feel like I had to hide anymore.

After that, I got invited to MIT to a convention called ROFLCon in Boston, which was about all the memes of the time. I spoke at that and also went to this celebration of parody law in Washington, D.C. I also got invited to the Tumblr offices and was getting interviewed by all kinds of publications. I felt like a rock star for about a year.

I used to get tons of emails from all sorts of people, and a lot of them were suffering from depression. They were always saying, “Thanks for doing this. It really shines a light on the mental process that I’m going through. It’s nice to be able to laugh at my depression.”

I also got tons of hate mail from Garfield devotees saying, “How dare you!? Who do you think you are!? What gives you the right to deface the original Garfield? It’s not funny what you’re doing!” I couldn’t believe how furious they were.

As for the book, Paws Inc. asked me how they should go about it. I had the analytics and am an IT geek, so I could see the strips that people read most and told them which to use. The book was split in half — half were strips I made, and half were ones from Jim Davis/Paws. I wrote an introduction to the book as well. In it, I talked about how, as a teenager, I had long hair, was in a garage band and wanted to be in Rolling Stone. I never got anywhere because I sucked, but then, 15 years later, thanks to Garfield Minus Garfield, I finally got to be in Rolling Stone — just not for the reason I thought I would. And I’m tooting my own horn here, but I was also in Time magazine. The Dalai Lama was on the front page, and I was on the back page.

When the book came out, I didn’t get a free copy. I had to pay for it! I did get a discount, though, and bought about 50 copies. I kept giving them away to people until I had none left. I then had to start looking on eBay, and I bought some secondhand copies. I have about five of them now, and I’m not giving those away.

‘Garfield Minus Garfield’ in Repose

I kept doing a strip every day for a few years after that, but I slowed down around 2014 when I became a dad. Still, every few months, I’ll throw another one up just to keep it alive. There’s still a good community on Facebook with 100,000 people. It’s still got about 300,000 followers on Tumblr, too.

I’ve tried to analyze why Garfield Minus Garfield appealed to me and so many others at the time. I think the answer is that Garfield was no longer relevant at that point. We all had it as a kid, but the humor was a bit old school, and we’d all grown out of it. Still, we had a bit of nostalgia for it, and Garfield Minus Garfield made Garfield relevant once more. People liked to be able to laugh at those same comic strips that they used to laugh at.