In 1913, the German artist Winold Reiss arrived on American shores with aspirations common to many immigrants: he was in search of the opportunity to have a better life. But unlike the countless others that reached the United States in the early 20th century, Reiss was bringing an artistic revolution with him. A force for the modernism that was thriving in Germany at the time, Reiss was destined to make a deep and lasting impact on the shape of American art, showcasing his talents in realms as varied as restaurant interiors, advertising, metalwork, portraiture, fashion and furniture.

Reiss is the subject of a new show at the New-York Historical Society that aims to resurrect his legacy and put him back on the map as the force that he was. “I want to show the public the extent of Winold’s life,” said the show’s co-curator Marilyn Kushner. “To make people recognize that he’s an important part of the canon.” To that end it has convened a major re-entry for Reiss, with an exhibit of 150 pieces that begins to lay out the full breadth of the man’s immense talents and prodigious output.

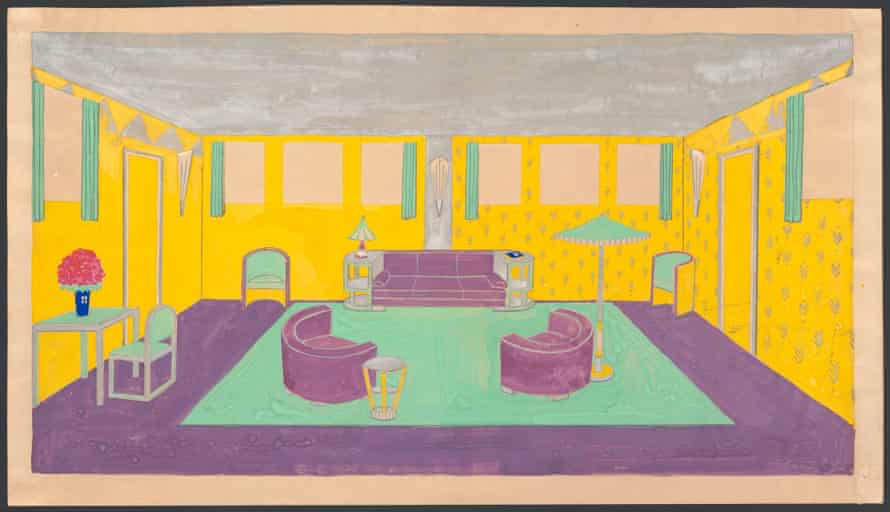

Reiss immigrated when he was 26, and by that time he had long been immersed in the modernism that swept over Germany throughout his youth. He was taught that anything at all could be art, and this was the ethos he put into his work in New York City, founding a magazine, designing bold, bright book covers and advertisements, creating wild furniture, and most of all raising his star himself by painstakingly building remarkable restaurant interiors. Through the dozens of interior spaces that he created, Reiss was able to redefine the experience of dining and drinking in New York City. He construed his spaces as a Gesamtkunstwerk, a single unified artwork that comprised everything from ornamentation and murals to lighting, seats, mirrors and even ventilation. He did it all with bold, bright color that could not be more different from the dreary, gravy-like brown that had dominated the restaurant scene.

“Hundreds of thousands of people in New York saw Winold’s work but they never knew who he was,” said Kushner. “His restaurants were so recognizable, and they knew them. People didn’t want restaurants to look like brown gravy, they wanted them to look happy.”

Although Reiss was widely known and celebrated in his time, in the decades after his death in 1953, he became forgotten. The restaurants that he worked so hard to bring into being were torn down to make way for newer styles, and his work became scattered among private collections, archives and smaller museums throughout the US.

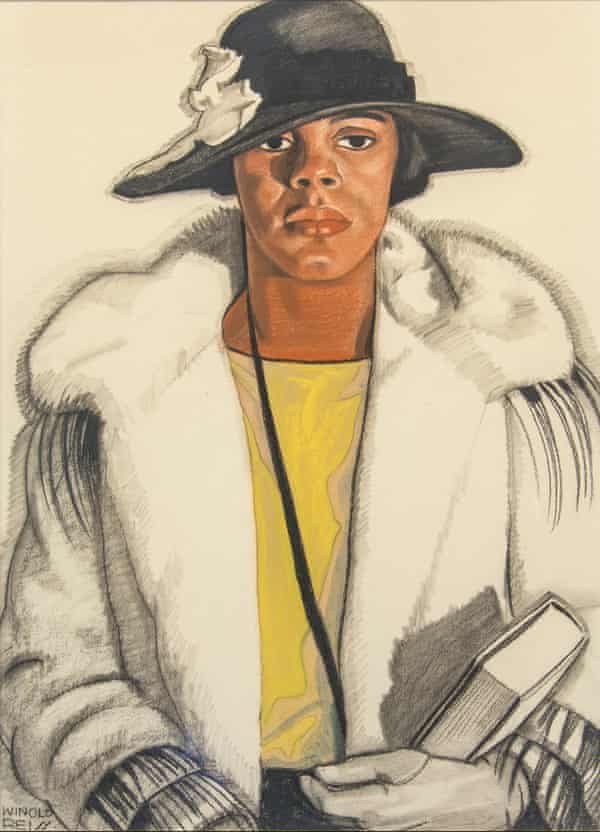

Part of Reiss’s genius was that he brought an outsider’s perspective to the United States. Believing that New York City would be an excellent place to see Native Americans practicing their particular way of living, he came to America with a large degree of naivety. He also always felt on the fringes of society, speaking with a German accent for his entire life and never truly feeling at home as an American. According to Kushner he was able to make his self-identification as an outsider work in favor of his art. “Because he came to New York as an outsider,” said Kushner, “he was able to get into people’s minds and give them an elegance and self-respect. He was able to get to their soul, and that’s important for us to think about today, to really appreciate various ethnicities.”

That outsider’s perspective is at the heart of the New-York Historical Society’s expansive exhibition, whose broad collection of diverse pieces is constantly surprising and invigorating. The work runs the gamut from prints and plans for interior design to woodcuts, advertisements, dozens of portraits, wild art nouveau–like cityscapes, even iron gates and remarkable wooden chairs. Reiss’s mastery can be seen in evocative portraits of Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes, a haunting, expressionistic woodcut on the theme of love, a book cover for Knut Hamsun’s Shallow Soil and a gorgeous, lush imagining of Woodstock. Overall, the New-York Historical Society’s exhibit has a freshness and an eclecticism that make it worth visiting and lingering.

For Kushner, who has worked as a curator throughout New York for nearly 30 years, Reiss’s work was instantly captivating. “I remember one afternoon I walked into the head of the library’s office, and he showed me the work of Winold and asked if I’d be interested. I said ‘absolutely!’ The minute I saw it I wanted to do an exhibition of his work.” Kushner found Reiss’s art so complicated and expansive that it took her about six years to properly assess it all and put together a large-scale exhibition. “He was so curious about everything, and you see that curiosity coming through in the wide range of topics that he chose for his art.”

Although Kushner recognizes the genius of Reiss’s work in a variety of formats, it’s his portraits that stand out as most spectacular to her. Citing their intensity and simplicity, Kushner admires them for their ability to pierce into a viewer, while also offering an experience that’s breathtakingly beautiful. She also admires their psychological complexity and how they dig deeply into the profundities of their subjects. “The way Winold was able to express the personality of his subjects through these small details was, I think, genius. He was able to really get inside their heads.”

For Kushner, this is hopefully just the beginning. While the New-York Historical Society’s exhibit focuses on only Reiss’s New York–based work, he traveled widely throughout the United States, painting what he saw and leaving his mark through large-scale work like murals. Kushner has plans to keep exhibiting and promoting Reiss, eventually attracting collaborators who can give Reiss the treatment that his work deserves. “This is not the final Winold Reiss exhibition. I haven’t brought in so much of his work with Indigenous people, or the fantastic mural he did in Cincinnati. There’s a lot more research to be done on Reiss. There’s really a goldmine of future research to be done on him. This exhibit is opening the doors to all kinds of possibilities.”