Two major forces, distinct but not unrelated, are causing turmoil for writers: massive labor struggles and accelerating advancements in artificial intelligence.

On the labor front, streaming businesses like Netflix have robbed TV writers of residuals; song lyricists have been decimated by Spotify; and book authors have been squeezed by consolidation in both publishing and bookselling. Though their work has brought billions of dollars into the American economy, the writers themselves are consistently treated as disposable.

Will AI make things even worse? At the moment, worries over AI-written scripts are helping to fuel the ongoing Writers Guild of America strike; thousands of people have signed an Authors Guild petition calling on AI industry leaders to compensate writers; and a series of pending lawsuits brought by writers allege copyright infringement of their work.

As we think about AI’s potential to automate labor in writing and other industries, I wonder whether our society might finally move toward universal basic income and a reduced work week — or if wealth disparities will continue to grow with more and more people living in poverty each year.

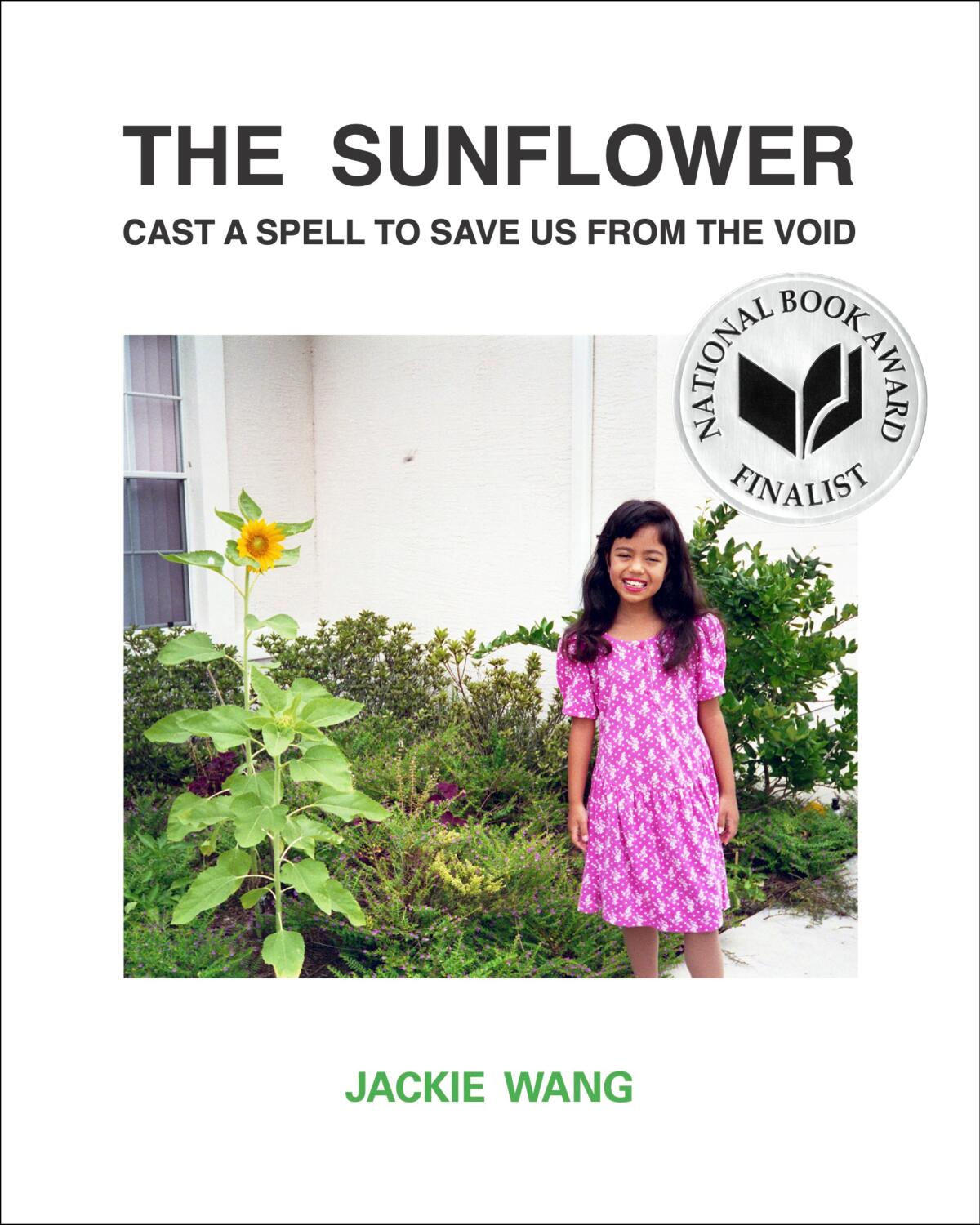

Jackie Wang is uniquely positioned to make sense of this precarious moment. A poet, scholar and assistant professor of American studies and ethnicity at USC, her poetry has been shortlisted for a National Book Award and her influential academic work includes titles such as “Carceral Capitalism.”

Over the past few months, Wang and I have engaged in a wide-ranging exchange over email — edited here for length and clarity — about how AI has already changed us and what may be on the horizon, for writers and humans at large.

Jackie Wang, a poet and assistant professor at USC, has mixed feelings about how AI will change the world of literature.

(Sasha Pedro)

Recently we went for a hike and talked about the intersection of literary production and artificial intelligence. You described us as part of “the last generation to experience raw human emotion.” Can you elaborate on this?

Let me clarify that remark. We’ve been cyborgs and pharmacological hybrids for a long time. I don’t think there’s something like an ideal state of authentic humanness, nor do I think that humanness is better than non-humanness. What I’m referring to is the saturation of distractions, which for me reached a crisis point during the pandemic, when my existence was almost entirely mediated by the internet. I became palpably aware of how the very rhythm of my being is regulated by technology designed — using behavioral science research — to be addictive by hijacking the dopamine reward system. I think people dramatically overstate their “will” and “agency” in relation to technology.

I’m curious — maybe even interested — to see some of the mechanics of literary production transform. You are a bit more hesitant. Why so?

Maybe on some deep level I have a sentimental attachment to the way “writing” has been done for over 5,000 years. From cuneiform clay tablets to computer keyboards, the writing process has changed very little for thousands of years. It was probably ripe for disruption. But I’m ultimately disturbed by the collective effect it will have on language use — the move toward a statistical norm and the treatment of language as purely informational. I had already started to fret about this when Gmail started autocompleting my emails.

Will the weird, jagged, irregular effusions of language gradually be purged? For me, being a poet is not necessarily about the production of poetry but about the training of a certain kind of consciousness: the dilation of perception and emotional states, the sensitization of one’s antennae, the tuning of one’s soul for a greater awareness of the mystery of existence, its splendors and absurdities.

Perhaps I’m hopelessly modernist in my view that language is not about transmitting information or even advancing a plot but the wayward movement of a thought: the sentence as a technology of consciousness, with its serpentine twists and turns, perverse digressions and rhythmic pulsations.

Can emotion or spontaneity ever be captured by an algorithm?

The AI can convincingly mimic emotion. Tell ChatGPT about your problems and you will feel like it really cares, just like you might feel when you are personally addressed, by the language of advertising, written in a voice of concern or understanding. But I think unlocking a weirder side of AI might involve finding ways to break or mess with it so it doesn’t just generate mediocrity.

What would you consider to be the start of collaborations between writers and machines? I used to find myself fascinated by Rupi Kaur’s instapoetry as a closed poetic form that is responsive to algorithms.

We’re always collaborating with technology. Since I’ve written most of my works longhand, I often think about how the technology of the computer actually changes the texture of my thinking. Technology can also shape the “form” of writing — think of the character limit of Twitter. We’ve certainly reached a point where AI is directly shaping the written work.

“The Sunflower Cast a Spell to Save Us From the Void,” a book of poems by Jackie Wang.

(Nighboat Books)

I recently watched a panel in which one speaker described AI as a democratization of the creative process. Can you speak to this?

Whenever I hear a technology described as a “democratizing” force, my “ideology” alarm bells go off. People can talk about the democratization of the creative process, but that still does not alter the parasitic business model at the heart of cultural industries. For instance, publishing has been consolidated and now there are only a few major publishing houses. I think discussions of democratization should also address corporate concentration.

In regard to labor, we’re looking at a possible scenario in which writers will essentially become prompt makers and editors of computer-generated responses. What do you think this would mean for literary production?

We may soon reach a point where certain types of writing — screenwriting, journalism, web content —and certain para-literary activities — editing, proofreading, researching — could be fully or partially automated. Some say the new job will be “prompt writer.” There may soon come a day when plot-driven commercial fiction is written by AI with the help of prompt writers.

A lot of writers support their literary practice through commercial writing and editing; some of those jobs might disappear. In recent decades, it’s already gotten so difficult to survive economically as a writer. But it’s gotten hard to survive in general, given how obscenely high rent is these days. You can’t just scrape by on almost nothing and hope it works out at the end of the month. Art suffers when subsistence costs are high — it becomes more commercially driven, and artists become more “professionalized.”

How is AI going to redefine such concepts as originality and plagiarism? We have already seen some examples of this in the music industry, including AI-generated songs using the voices of musicians.

The voice imitation software trips me out. I started doing research on voice surveillance in early 2019 and tested out some voice-mimicking technology then. It was terrible. Now, it can replicate someone’s voice with uncanny accuracy.

I don’t feel particularly attached to an idea of originality. Mixing, collaging, generating new things by constellating old things — it’s all part of the creative churn. But the question of how artists will support themselves when technology enables endless, free replicability is a question that needs to be addressed.

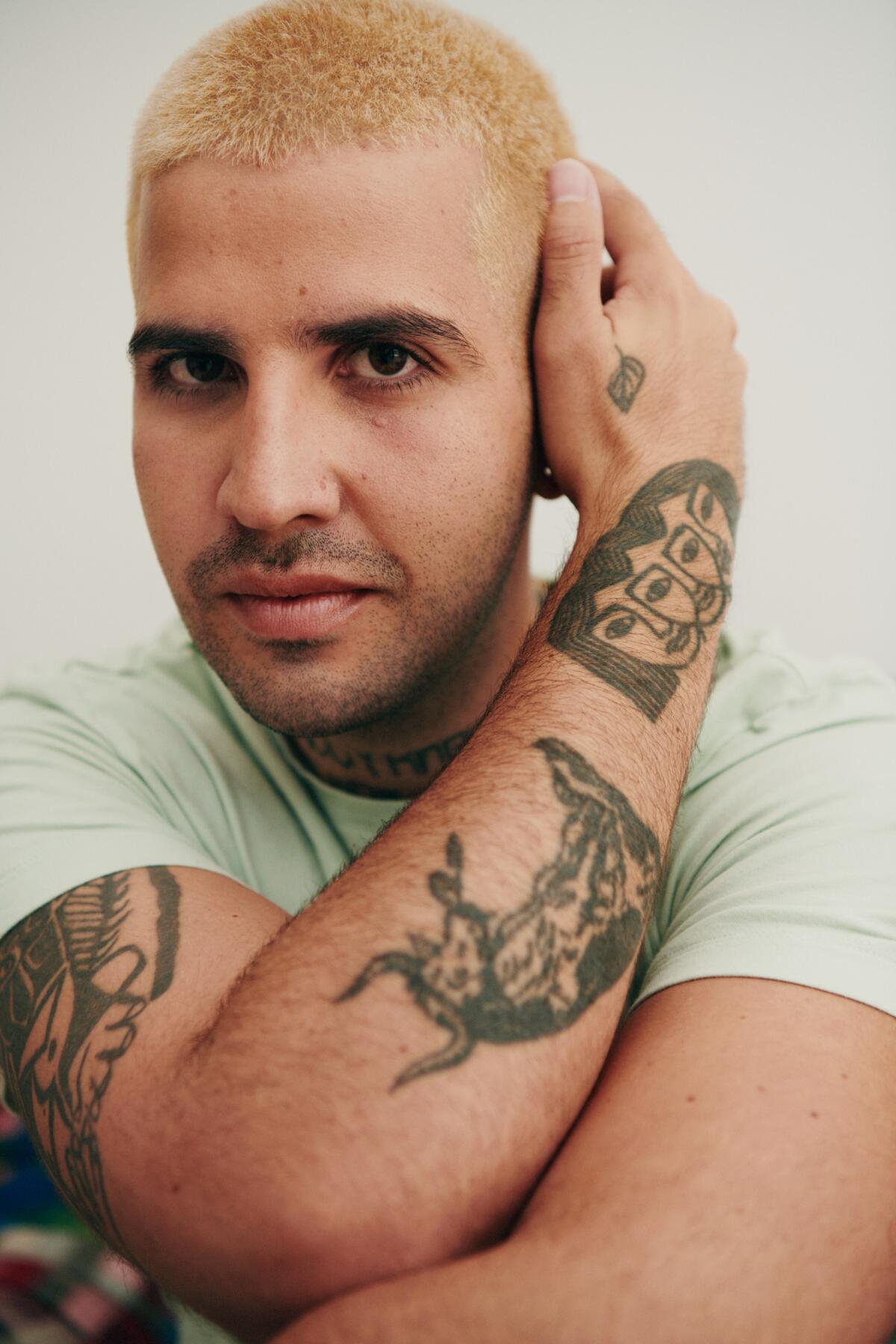

Poet and writer Christopher Soto in Los Angeles.

(Daniel Kim / For The Times)

To protect writers, should laws restrict the use of AI in particular fields?

Since I’m fundamentally against private property, I’m against intellectual property as well. In the early days of the internet, there was a movement to create a digital commons by making knowledge and culture free, open and accessible through alternatives to a copyright model. Intellectual property law creates artificial scarcity for goods that could be available to everyone for free.

But since we live in a market society, we must pay attention to the question of how writers are going to be able to put food on the table. The fact that generative AI is parasitic on the archive of human creativity is fundamentally a labor problem. Should AI be allowed to imitate living writers and artists, and will the imitations be commercialized at the expense of living creators? Should AI be able to clone the voice and image of living actors? No, I don’t think so. I’m ultimately in favor of enshrining strong labor protections for living creators.

When thinking about AI and the labor question, there is a tendency to focus on the front end rather than the back end, on the white-collar jobs that will be automated, not the underclass of taskers labeling and training data. AI relies on workers to annotate data and to refine the results generated by AI through a process known as “reinforcement learning from human feedback” (or RLHF). These annotators are paid $1.20 an hour in Nepal by companies like CloudFactory. In Kenya, annotators with Remotasks are being paid between $1 and $3 per hour.

Are there any parallels between what is happening now and the Industrial Revolution?

There are definitely parallels with the Industrial Revolution, which put our species on this path of ever-accelerating accumulation. Well, some say it all began with the Agricultural Revolution. Large Language Models and generative AI will profoundly reshape the economy, leading some industries to collapse completely. The education technology company Chegg was the first to crash. Other industries will be profoundly transformed. This tendency toward creative destruction is an inherent feature of capitalism.

Generative AI will make humans more “efficient” and “productive.” But what is all this efficiency for? Technology has been evolving at breakneck speed since the Industrial Revolution and we are still working just as long and hard. Efficiency has become our bondage. Once the logic of accumulation enters the bloodstream, it seems hard to stop, partly because accumulation is bottomless — that is, until we hit a hard ecological limit.

I wish writers could just sit around and be dreamy instead of having, to borrow the words of Robert Musil, to “eat steak and keep moving.” I do hope we one day arrive at a postwork society. It makes me sad to think that we’ve tacitly accepted a system where we spend our lives toiling for the profit generation of the ownership class, squandering our short, precious life on this planet.

What can the poetry economy teach us about the future of literary production with AI?

The thing I love about poetry is its uselessness, the way it is, with a few exceptions, superfluous to capital, difficult to commodify, gratuitous in its insistence on avowing that which has been marked valueless. How many poets do you know who can support themselves on their poetry alone? I think I know zero. Mostly, I know poets who teach in the academy, poets who do astrology, poets who work as editors at publishing houses, poets who have office day jobs, etc. Maybe generative AI will create a glut of language that will make poets (and other literary writers) even more superfluous, ha!

Soto’s debut poetry collection, “Diaries of a Terrorist,” was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2022.