Somewhere in writing The Power Fantasy, an original Image Comics series with artist Caspar Wijngaard (Home Sick Pilots, Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt), Kieron Gillen paused for thought.

“I realized, Oh no, this is probably my last word on the genre. Everything I learned about [superheroes] I’m putting in this book and trying to make it the best-possible pop version of it,” he tells Polygon. “Never say never, obviously, but it feels like it.”

A veteran of lauded runs on Young Avengers, Eternals, and multiple X-Men eras — not to mention several blockbuster meditations on power, like The Wicked + The Divine and Die — Gillen has a lot of experience to go around. With The Power Fantasy, he and Wijngaard are walking the same path as books like Watchmen, The Boys, Kick-Ass, or Invincible. And with the first chunk of the story hitting shelves in collected edition this week, Polygon talked with Gillen about playing the game of deconstructing superheroes — and which of Power Fantasy’s six world-ending superhumans he finds most terrifying.

But when comics creators and filmmakers take aspects of the superheroes conceit and push them to darkly logical conclusions, can it even be called deconstruction anymore? “The thing about this mode of superheroes is it’s been around for at least 40 years,” Gillen pointed out. “So in other words, the idea [that it’s] deconstruction really doesn’t hold true anymore. These books could very easily be someone’s first superhero comic. It’s no longer actually deconstruction, it’s now just how [superheroes] are.”

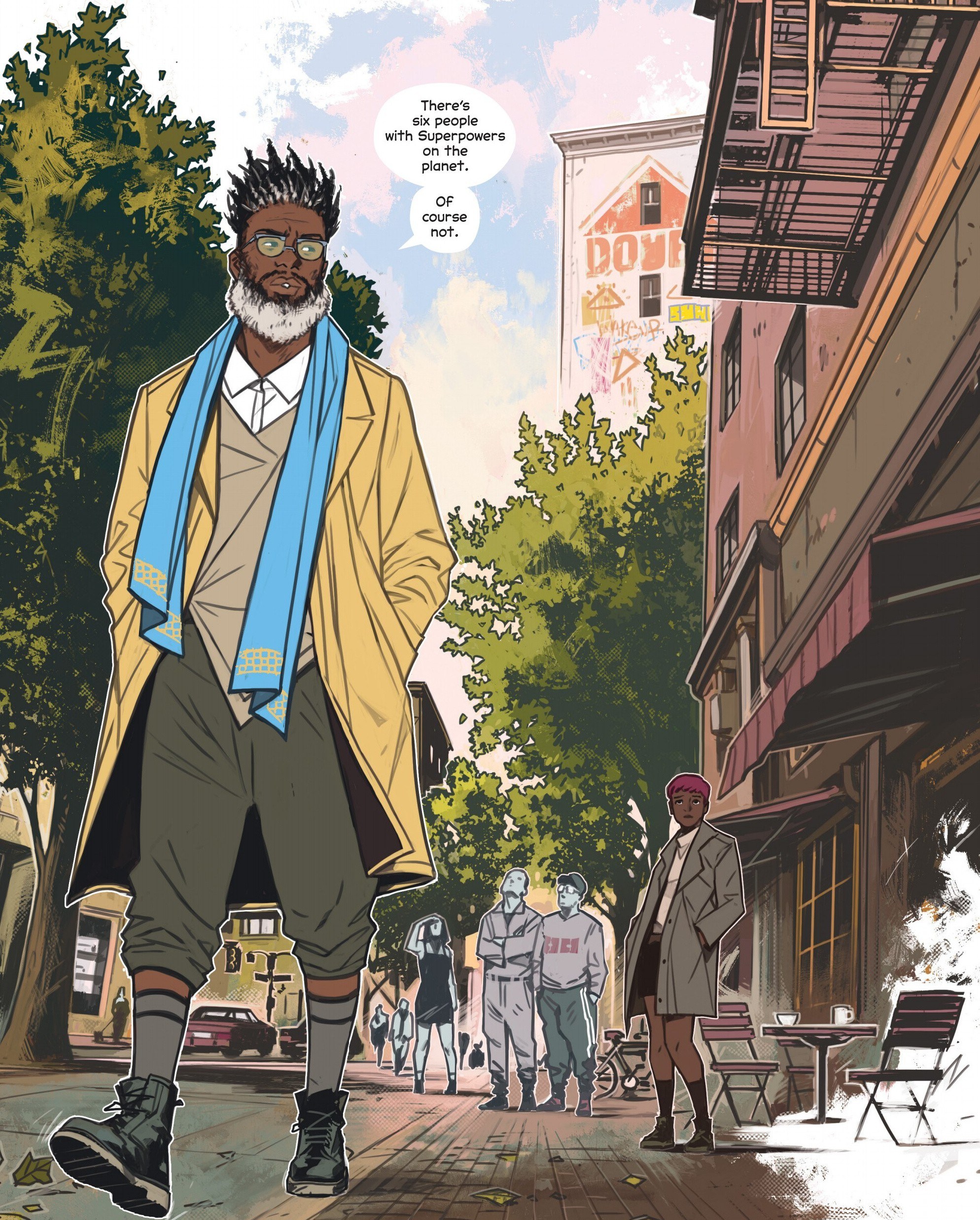

The way things are in the world of Power Fantasy is this: The word “superpower” is no longer associated with fictional superheroes, but any of the six known human beings whose own natural abilities have equivalent destructive potential to “the nuclear arsenal of a major world power.” Gillen and Wijngaard’s story presents these six Superpowers alongside post-nuclear nations, with an accompanying alternate history of the late 20th century that has been shaped by the virtuous Valentina, the telepathic Etienne, the gravity-powered Heavy, the tragic Matsumi, the cultish Magus, and the still mysterious Eliza.

All six of them could bring about the end of the world on their own, and certainly would if they ever came to blows between themselves. And so The Power Fantasy is about the testy, global balancing act between these six very human people, each with their own motivations, dreams, and philosophies of the purpose of power.

Knowing that these kinds of deconstructions thrive on reflecting superhero universes to their audiences using recognizable archetypes — Doctor Manhattan and Homelander as reflections of Superman, for example — we asked Gillen which archetypes had seemed most important to include in The Power Fantasy.

“I started with the [Professor] Xavier archetype. I started with the telepath [Etienne Lux].” Part of that, Gillen said, simply came from the observation that superhero deconstructions usually reflect DC Comics characters more than Marvel ones. “They always hit those really early characters, because they’re playing with the foundations of the genre, because Marvel was a deconstruction-ary company.”

But much of his inspiration also came from his recent stint on Immortal X-Men, and other flagship X-Men books at Marvel Comics. Gillen said he was “writing Xavier and [he] was like, Oh my God, I could do so much more with a telepath if I wasn’t writing at Marvel.”

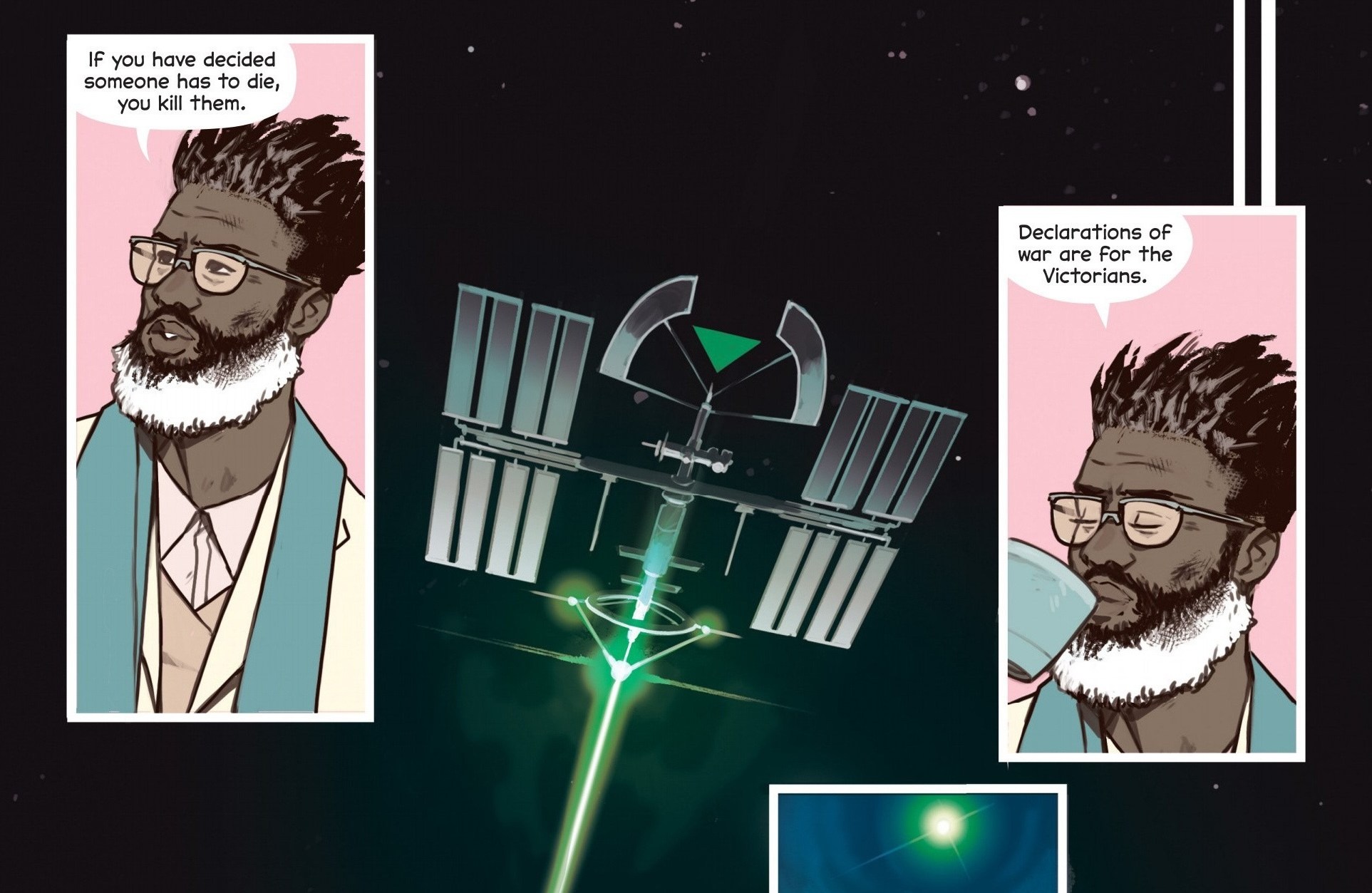

In The Power Fantasy #1, Etienne defuses a Superpower standoff by using long-distance telepathy to assassinate the president of the United States, so that Heavy won’t throw the entire state of Texas into orbit. “I think telepaths are really interesting,” Gillen said, “because they’re fundamentally creepy. It’s very telling that the very first super[powered] character [Siegel and Shuster] made, the first Superman, was a telepath […] and they were a bad guy.”

From his Professor Xavier “serene philosopher telepath” archetype, he naturally needed a corresponding “rebel” — which led him to Heavy, the post-hippie commune leader with world-ending powers over gravity. “I think I called him the Free Radical as a joke in my head,” Gillen said. “A 1960s White Panther, Detroit rebel is a very different kind of energy to Magneto.”

But, between the formation of Etienne and Heavy, “Valentina came in quite hard.” Born fully sentient and Superpowered in São Paulo at the same moment that the U.S. Army first detonated a nuclear bomb in New Mexico, Valentina is an indestructible, omniscient, flying woman who claims to be an angel sent to reality to protect humanity from its own capacity to destroy itself.

Valentina is “the person who has actually taken the classic superhero argument, We can’t intervene [in human power structures],” Gillen said; his Superman and Wonder Woman archetype rolled into one. But “there’s a bit of America Chavez in her; in fact, [America meets] Marvel Boy, actually,” he acknowledged, referring to two superheroes featured in his and Jamie McKelvie’s Young Avengers. America, for example, came to our plane of existence because there were no great heroic challenges left in her utopian alternate dimension. “On some level it’s me hitting ideas that I’ve flirted with before and being dissatisfied somehow and doing a better version.”

Aside from the superhero archetypes he wanted to work with, Gillen also naturally had to consider how to combine personalities and powers so that the actual story he and Wijngaard wanted to tell would flow logically.

“If I did the wrong group of characters — or not wrong,” he corrected himself, “but [poorly balanced] — immediately the history goes spinning off.” Valentina’s commitment to noninterference and her omniscience “fundamentally stops Etienne from taking over the world,” shaping humanity’s minds to his own study of ethics. “If Etienne could do it without Valentina knowing, he would’ve done it,” Gillen laughed, “and then it would be like, Whatcha gonna do, Valentina? You can kill me, sure, but I’ve saved the world.”

All six of the Superpowers are capable of ending the world, but which of them does Gillen personally find most terrifying? “I think they’re all petrifying in different ways,” he said, but “Eliza’s the character I’m most scared of, I think.”

But given that Eliza’s powers and personality have yet to be explored in The Power Fantasy’s first five published issues, Gillen also offered an option he could actually talk about: Etienne Lux, the Superpowers’ own philosopher-diplomat-president-assassin.

“Etienne is probably the scariest,” Gillen said, “or at least is the person who is the most explicitly scary in how he does things. The thing that Etienne knows is, if shit goes down, it’s too late for him. […] What can he do if the world’s actually ending? I can turn off people’s pain receptors.

“So,” Gillen says, “he’s got to do stuff in advance.”

Etienne, after all, believes that the superpowers should act to create the greatest good for the greatest number of people. And in a world where coming into direct contact with any of the other five Superpowers would lead to the destruction of humanity, well…

“What can a utilitarian justify [himself] into doing?” Gillen asked. “And that’s one of the problems. The second you start dealing with death of the world on one end of the utilitarian scale, what’s justified, then? That’s fundamentally petrifying.”