Family is the most important thing in the world. At the same time, we all have family members who get on our nerves. Racist uncles, deadbeat cousins, obnoxious in-laws, lazy siblings, etc. Hopefully, you don’t have too many of these individuals in your extended family. But what if you did? Imagine a terrible universe where you hated absolutely everyone in your immediate family. To make matters worse, imagine a universe where you are extremely wealthy, and all of these awful relatives can’t wait for you to die so they can inherit your estate. What would you do? Well, if you’re 19th-century lumber and mining baron Wellington R. Burt, you concoct what is arguably the most bizarre and vindictive will in American legal history…

Early Life

Wellington R. Burt was born on August 26, 1831, in Pike, New York (near Rochester) into a poor farming family. He was the ninth of 13 siblings. And despite being the ninth-born child, he was actually the first-born son. Imagine the bathroom line in that house on Friday nights.

When Wellington was seven, his entire family moved to Jackson County, Michigan, where they were able to purchase a much larger piece of land to farm. Michigan had only been a state for a few years (since 1837), and families like the Burts were incentivized to move out from the East with cheap plots of fertile farmland.

When he was 12, his father died, and Wellington became the head of the family and farm. It was an enormously difficult task and instilled in Burt a furious work ethic and cold personal disposition that would remain throughout the rest of his life.

When he was 20, Burt managed to attend two year’s worth of college.

At 22, he felt comfortable enough to leave the family farm for an extended period, so he took up work as a sailor on freighters that were bound for Australia, New Zealand, and South America. The future tycoon cherished his time in Australia, especially the city of Melbourne.

Wellington returned to Michigan in 1857 at the age of 26. In those days, Michigan was in the early stages of an explosion in the lumber business that would later be called the “Green Gold Rush.” Upon his return, Burt got a job at one of the lumber camps. The job paid $13 a month, equivalent to $350 a month today. Within a few weeks, Burt was made foreman of the entire camp, and his monthly salary was doubled.

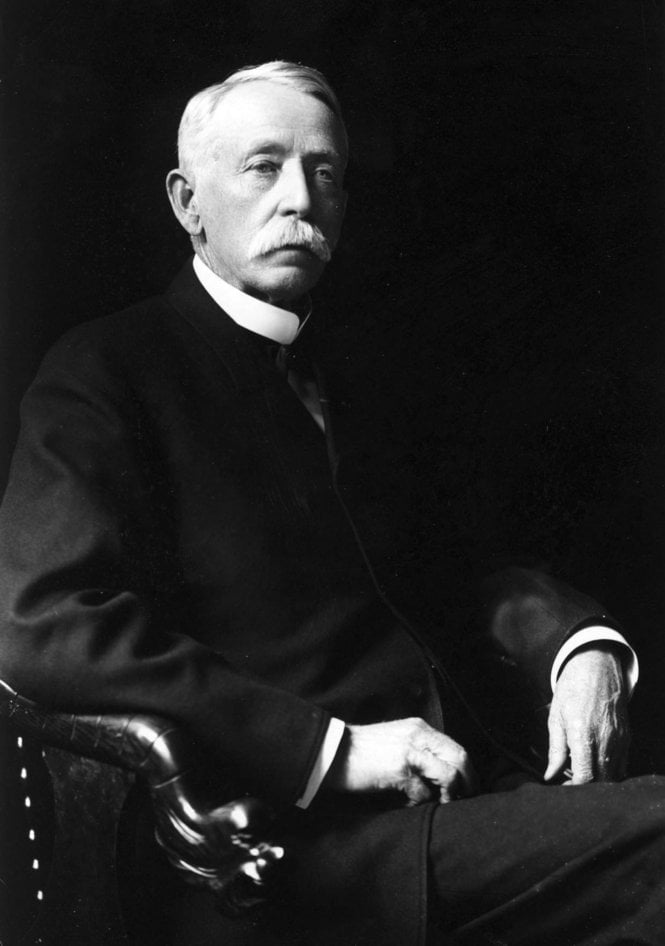

Wellington R. Burt (Public Domain)

A Fortune Is Born

Having grown up mostly dirt poor, Wellington very much understood the value of saving. He lived modestly and pinched every penny so that within a year, he had enough money to buy 320 acres of land in what is today called Gratiot County, Michigan.

His lumber business was soon flourishing. Over the next decade, he acquired more and more land, especially around Saginaw County, Michigan. In 1867, he founded a full-service lumber community along his Saginaw River property, which he named Melbourne, after his favorite city from this time as a sailor. Within a few years, Melbourne was one of the largest lumber mills in the world.

Unfortunately, Melbourne was destroyed by a fire in 1876. Had Burt not continued his habit of saving and diversifying, it surely would have bankrupted him forever. As his mills were being rebuilt in Michigan, Burt began focusing on land he owned in Minnesota, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. As luck would have it, in addition to timber, the land in Minnesota also turned out to contain large quantities of iron. Later known as the Mesabi iron range of Saint Louis County, it would turn out to be one of the largest discoveries of iron in American history.

The iron discovery transformed Wellington R. Burt from a moderately successful lumber businessman into a multi-millionaire.

Again, not one to rest on his laurels, Wellington diversified his timber and iron profits by investing in railroad and banking companies. He personally financed a railroad called C.S. & M. Railroad, which was eventually sold off to the Grand Trunk Railroad Company for a tidy little profit.

At his peak, Wellington was essentially the sole owner of all railroads coming in and out of various areas of Michigan, especially Ann Arbor. Ever the worldly man, he even bought railroads in China and Russia at a time when that was utterly unheard-of. Burt also launched a political career that included an unsuccessful run for Michigan Governor, and a successful term as a state Senator from 1893-1894.

Thanks to the enormous success of his various business ventures, by the time Wellington was in his sunset years he had amassed a peak fortune estimated at between $40 and $90 million. That’s the same as $500 million to $1.2 billion in today’s dollars. Wellington was one of the 10 richest men in America during his time.

Skipping A Generation

Along the way to earning that fortune, Wellington married twice and had seven children and two grandchildren.

For a time, Burt intended to leave that fortune to his family and various state-run organizations in Michigan. That plan changed.

First, Wellington got into a spat with a local property assessor.

In 1915, when Wellington was 82 years old, he built a large fence around his mansion in downtown Saginaw. Maddeningly, building the fence triggered someone from the county assessor’s office to come out to the mansion to reassess his property taxes. When the assessment was done, instead of paying $400,000 for his various real estate property taxes, the county wanted Burt to pay $1 million.

Burt was incensed. He angrily told the Saginaw city council:

“You’d merely be killing the goose that laid the golden egg.“

[The implication being that they shouldn’t mess with a guy who was about to leave massive amounts of money to state and local causes…]

When the assessor wouldn’t budge, Burt met with his lawyers and immediately removed every state-run organization from his will.

Then there were the family feuds. It’s not entirely clear what exactly happened to cause Burt to hate his immediate family members. Here’s what is known, though – After his death, when Burt’s relatives eventually presented his will, they found 42 pages of detailed personal grievances attached.

Wellington was not done being vindictive with his will. Frustrated by years of neediness, feuds, disappointments, failed marriages, and general disagreements, Wellington instructed his lawyers to include literally what he called a “spite clause” in his will. The spite clause stipulated that his entire fortune be kept in a simple, minimal interest-bearing account at Second National Bank. Sounds ok so far, right? Well, unfortunately for his immediate heirs, Wellington also stipulated that his fortune be kept in that account without being distributed, until all of his children and grandchildren had died.

More specifically, he stipulated that the money would remain locked away until 21 years after the youngest grandchild, at the time of his death, had died. The will was handwritten by Wellington Burt himself. It was signed and notarized in August 1917.

To be fair he did set aside a few small annual payments to a handful of people. For example, some of his children were given annual gifts of $1,000 or $5,000. His favorite son was given an annuity of $30,000 annually ($400,000 in today’s dollars). One daughter was cut out completely. His longtime secretary was given $4000 annually ($54k today). His cook, chauffeur, coachman, and housekeeper were each given $1,000 a year ($13,000 in today’s dollars).

The Aftermath

Think about how brutal that must have been for his family members, who did not see this coming at all and did not even know if it was legal. As a matter of fact, some legalities were debatable. This type of will is called a “generational skipping trust,” and they are illegal in some states. One of the states it was illegal in at the time was Minnesota, where a large portion of the money had come from. As such, a year after his death, the family members were able to contest the will and successfully secure $720,000 in cash and $5 million in assets related to the Minnesota mines. It was a small concession. The vast majority of the fortune would remain locked up at Second National Bank in Saginaw until 21 years after the youngest grandchild died.

At the time of his death in 1919, Wellington’s youngest grandchild was Marion Lansill. Marion was born in 1905. So she was 14 years old. Had Marion died a year later, the family members – many of whom would likely still be alive – would inherit an enormous fortune 21 years later, in 1941.

Much to her relative’s frustration, Marion Lansill lived to be 84, dying in November 1989!

Marion’s death in 1989 kicked off a 21-year countdown clock.

In November 2010, the magic moment had finally come, but the surviving family members now had to meet with lawyers to figure out the most equitable way to pay out the funds.

In May 2011, after seven months of legal negotiations, Wellington’s millions were finally distributed. The estate, which by now had grown to $110 million, was distributed to 12 people:

Three great-grandchildren

Seven great-great-grandchildren

Two great-great-great-grandchildren.

Most of the beneficiaries had never heard of Wellington R. Burt. The average beneficiary received $2.9 million. A handful of the older heirs received around $14.5 million. The oldest beneficiary was 94 years old; the youngest was 19. The 19-year-old beneficiary was born in 1992, 72 years after her great-great-great-grandfather died. She and her 21-year-old sister both received $2.9 million.

In total, more than 30 possible direct descendants, most notably his children and grandchildren, died before being able to benefit from the trust. Bankers and lawyers who protected the money accumulated more than 40 boxes related to Burt’s will.

Today’s Equivalent

To put this in perspective, imagine your father is one of the ten richest Americans in the world right now. For example, let’s say your father was Charles Koch, whose $62 billion fortune presently makes him the 10th-richest American. Imagine if Charles Koch died tomorrow, leaving behind a generation-skipping will and a 14-year-old grandchild. And let’s say that grandchild lived to be 89 like Marion Lansill. At that point, a 21-year countdown would start. Fast forward to the year…

2117

Finally, in 2117, dozens of future Koch-heads suddenly inherit a fortune. Lucky for them. Not so lucky for the present-day Kochs 🙂