As the Walt Disney Company enters its centenary, marking 100 years as a film studio whose humble Midwestern beginnings didn’t hint at its coming transformation into a pop culture bulwark, it’s important to recall a common thread running through many of Disney’s early animated features. These were daring films that pushed the technological boundaries of their eras — often resulting in instant financial failure. Some of the biggest creative swings at Walt Disney Animation Studios occurred while Walt was alive, and are among the finest examples of animated art. And these films pushed the studio to the financial breaking point.

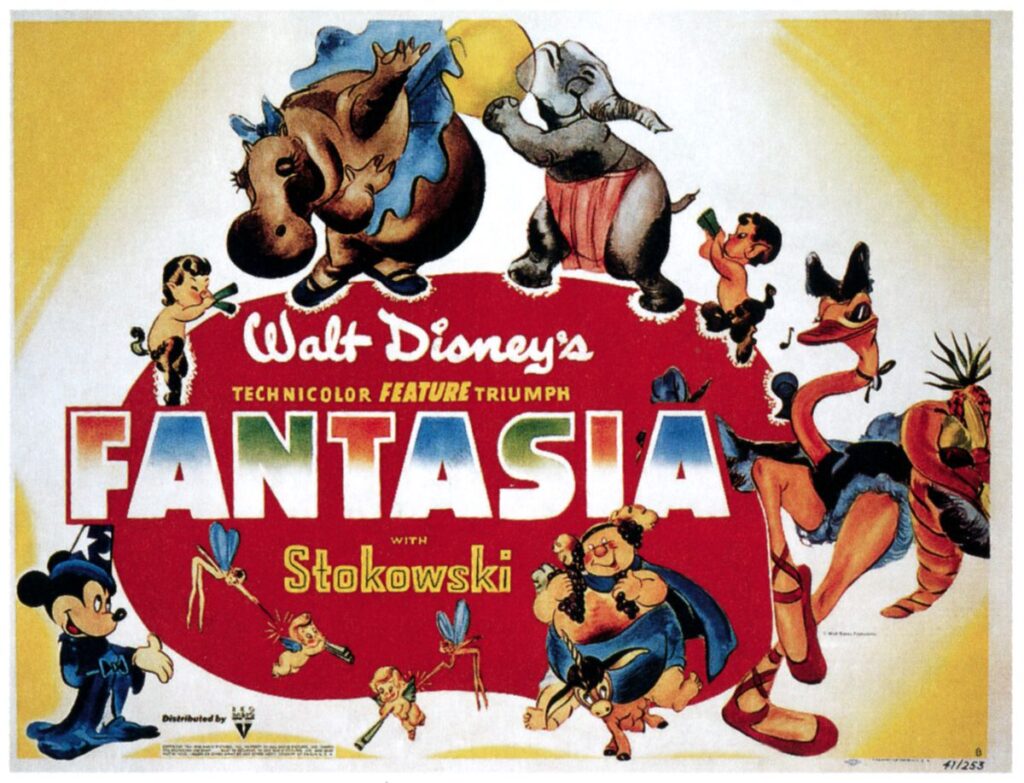

Those same titles eventually became some of the studio’s most beloved films, thanks to generational nostalgia, constant re-releases, the advent of home media, and Disney’s corporate skill at mythologizing its work. And there are no better examples of that reversal than two of Disney’s Golden Age titles, released one after the other: Fantasia and Dumbo.

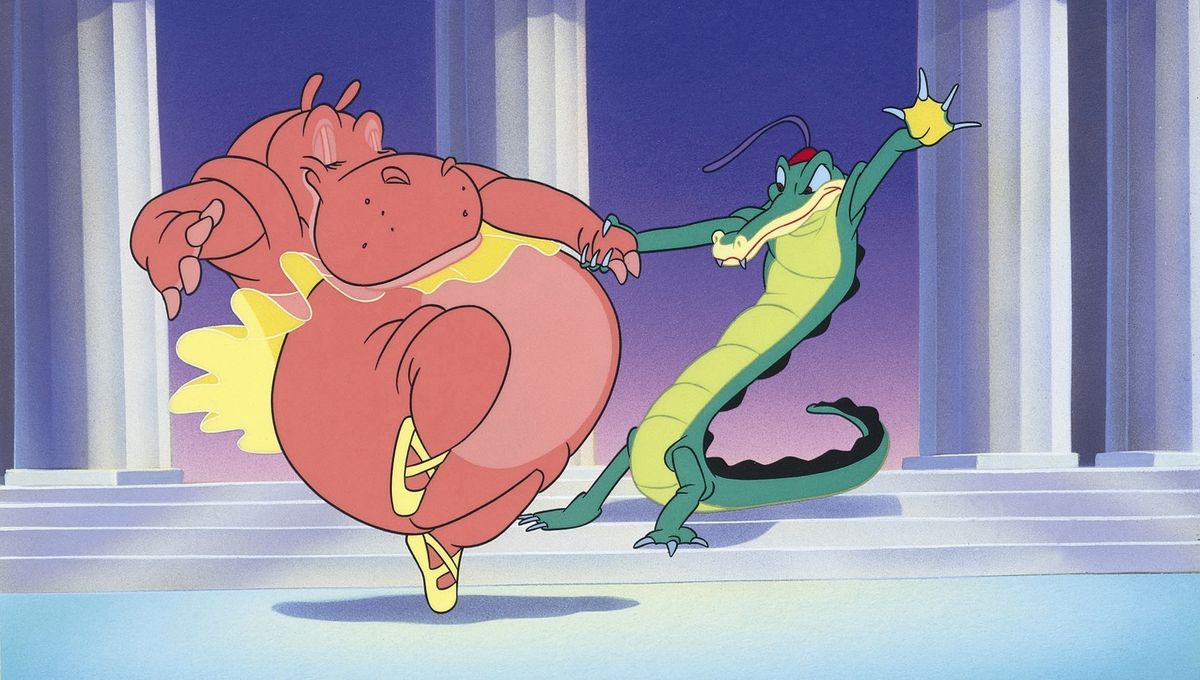

Fantasia remains the most ambitious film Disney Animation has ever produced, both on a surface level and upon deeper analysis. At 126 minutes, it’s the longest Disney animated film ever (and one of the longest animated films, period). It’s largely free of dialogue, apart from the interstitial sections overseen by opera commentator Deems Taylor. It’s scored to various pieces of classical music, so it has no overarching story. Some of its eight animated shorts are experimental enough that they don’t have identifiable characters or story arcs. And again, it’s a film overseen by an opera commentator.

Photo: LMPC via Getty Images

But the way Fantasia most pushed Disney to the financial brink was through its presentation. Just as James Cameron now wants audiences to experience Avatar: The Way of Water in 3D and the high frame rate format, Walt Disney wanted audiences to get the full orchestral experience with Fantasia, through a technique he dubbed Fantasound.

Fantasound is essentially stereophonic sound, which is now commonplace in professional theaters and home setups alike. But in the 1930s, the technology was rare and completely unavailable in movie theaters. Disney and his creative partner, conductor Leopold Stokowski, wanted to use the proposed short film “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” (the initial source of their partnership) to record stereophonic sound of Paul Dukas’ classical piece of the same name to accompany a story featuring Mickey Mouse as the eponymous apprentice.

After Fantasia premiered in November 1940, Disney explained his way of thinking to Popular Science: “We know that music emerging from one speaker behind the screen sounds thin, tinkly, and strainy. We wanted to reproduce such beautiful masterpieces […] so that audiences would feel as though they were standing on the podium with Stokowski.”

It was a noble idea, and it cost an exorbitant amount of money. Installing the 96-speaker system for Fantasound would cost each theater $85,000, or about $1.8 million in 2023 money. So few theaters offered Fantasound — just 12 of them opted for the technology to play Fantasia in a roadshow format. And since Fantasia cost more than $2 million at the time to produce, it failed to recoup its costs for years.

Image: Walt Disney Animation Studios

Over time, as the rest of Hollywood arrived at the notion that stereo sound enhanced the theatrical experience, Fantasia re-releases succeeded with new generations of viewers. Disney even managed to briefly lure audiences to the film’s 1969 re-release by leaning into the notion that the film could be a psychedelic experience for younger crowds. The re-release poster does make it look pretty trippy.

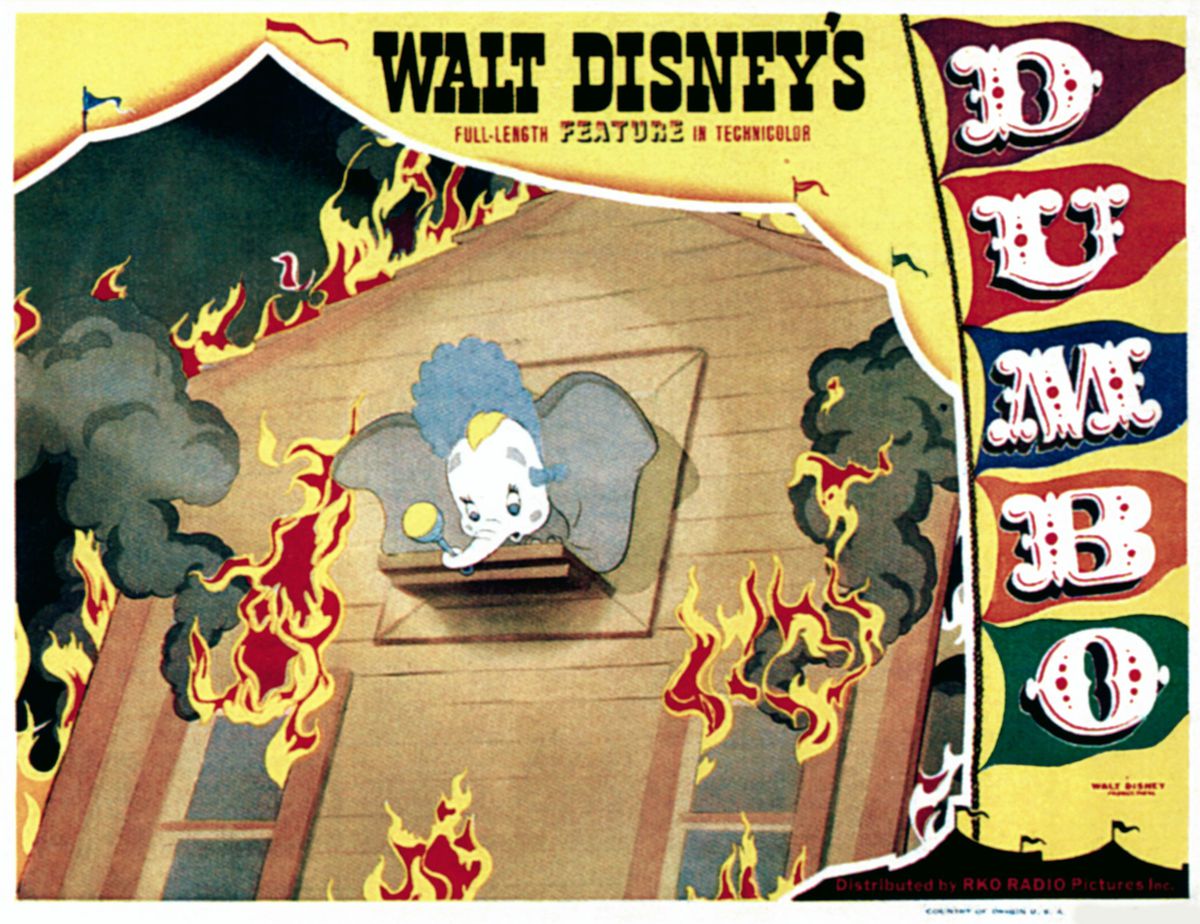

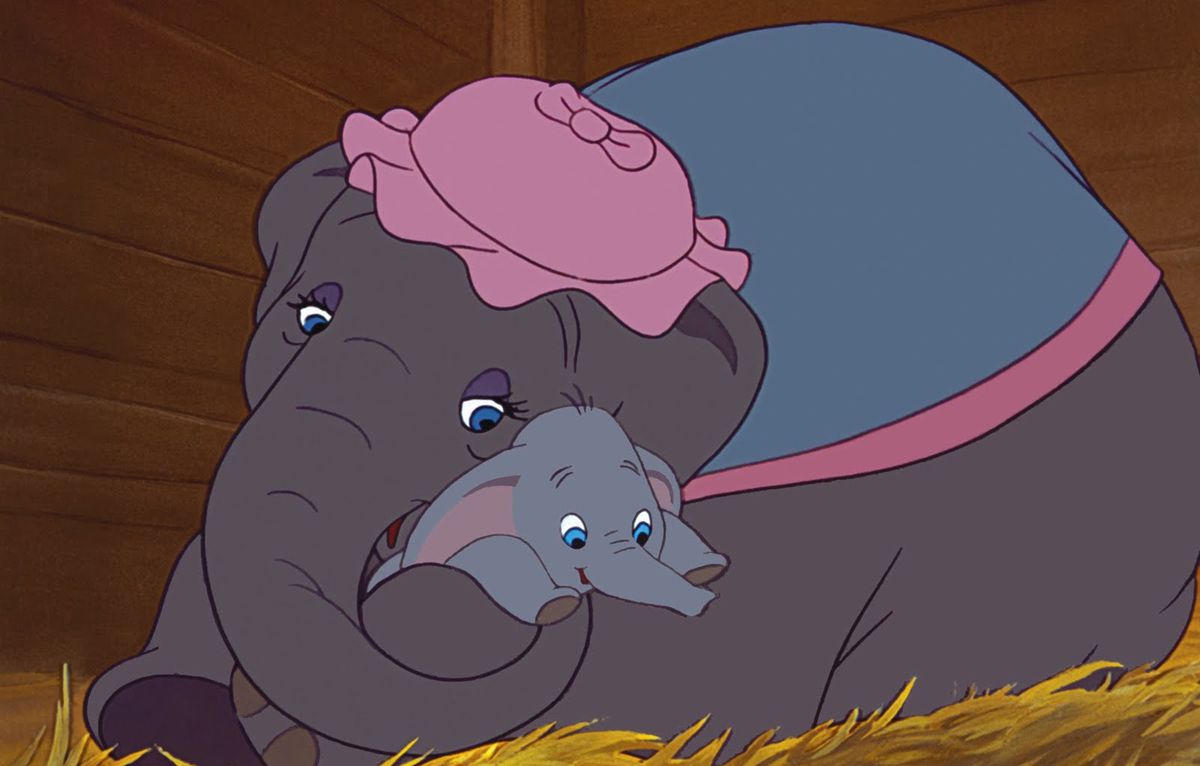

Just 11 months after Fantasia’s release, Dumbo succeeded by being, as Variety’s review at the time dubbed it, a “pleasant little story.” Loosely based on a never-published children’s book, Dumbo is somewhat experimental, though in a much more palatable way for wide audiences. The title character, a cruelly bullied baby elephant with inexplicably large ears, never speaks, and its kindly but fierce mother only says a few words herself. Though the sight of Dumbo triumphantly soaring in flight is one of the most recognizably iconic images in Disney animation, that image only arrives in the final 15 minutes. As pleasant as the story may be, it does feature Dumbo and his loquacious friend Timothy Q. Mouse getting drunk on champagne, then hallucinating a series of pink elephants on parade, an unusually psychedelic moment in Disney animation history.

And where Fantasia is the longest Disney animated feature, Dumbo is very nearly the shortest, clocking in at 64 minutes. (According to animation historian Bob Thomas in his book Walt Disney: An American Original, distributor RKO pushed Walt to make the film longer, and he refused.)

Fantasia’s box-office failure was one of a few aspects that contributed to Dumbo having a drastically lower budget of $950,000 — half the cost of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and two-thirds the cost of Pinocchio, per animation historian Michael Barrier. At the time, World War II was wreaking havoc on European culture, which further emphasized the need to limit spending.

Photo: LMPC via Getty Images

Dumbo was deliberately designed to be cheap without feeling sloppy — just as with Fantasia, every penny of the production cost is visible on screen, particularly in the more cartoonish, less intricately detailed character designs. Part of the budgetary trim was reflected in the animation style: Few Disney films use Dumbo’s less expensive background style, with watercolor images used to set the scenes. (While Snow White also has watercolor in some scenes, the other most famous Disney animated movie with watercolor backgrounds is 2002’s Lilo & Stitch.)

Creatively, the simpler style makes sense for Dumbo’s comparatively small story, just as the more expensive and highfalutin choices make sense for Fantasia’s ambition. (One of the most effective ways Dumbo hints at its children’s-story background is by depicting Mr. Stork delivering animal babies, soaring over the United States as visualized with an elementary-school-style depiction of Florida, with the state’s name hovering above it.) While these choices were a necessity, Dumbo doesn’t come across as a cut-rate or compromised production, unlike some later Disney animated movies.

The economizing paid off. Dumbo well outgrossed its production budget upon its initial release, and was easily the studio’s most financially successful film of the fairly lean 1940s. While Disney struggled to make feature-length films that hit with audiences during the Second World War, the studio started a re-release strategy in 1944 that not only reminded audiences of how beloved Snow White was, but helped films like Fantasia eventually make back their money.

Image: Walt Disney Animation Studios

It’s harder to square that long-term strategy against the current state of American theaters, when audiences are far less likely to return to multiplexes to watch movies they’ve already seen or can watch at home. There are exceptions, given a long enough timeline and a popular enough film: Cameron’s 2022 Avatar theatrical re-release made around $76 million worldwide, which helped offset the massive cost of The Way of Water. And many local theaters still hold special matinee screenings of popular kids’ movies — but that’s more on a scale to help those theaters make a profit than to boost movies’ long-term bottom lines.

The Walt Disney Company has changed a great deal since the 1940s as well. Like the other major studios, it’s risk-averse and aimed more at the coveted four-quadrant blockbuster release and the international crossover hit than at changing the medium of animation. While big changes like pushing into PG content with 1985’s The Black Cauldron, or moving away from hand-drawn cel animation in 2013, have periodically raised concerns about the company’s future, those concerns have rarely been as acute as they were in the 1940s, when the animation unit hovered on the precipice of disaster.

But in part, that’s because Disney has weathered so many crises over the last century, and survived so many risks like Fantasia and Dumbo, that it feels like too much of an institution to fail. These days, the company has far more freedom to take big chances with technology, trusting that the Disney name and legacy is a brand that will keep viewers coming back. New risks like the ambitious, challenging theatrical flop Strange World suggest that Disney is still willing to try new things to interest an increasingly busy and distracted audience, and it’s still willing to push the boundaries of animation — even if it sometimes seems like a risk without an easily predictable reward.