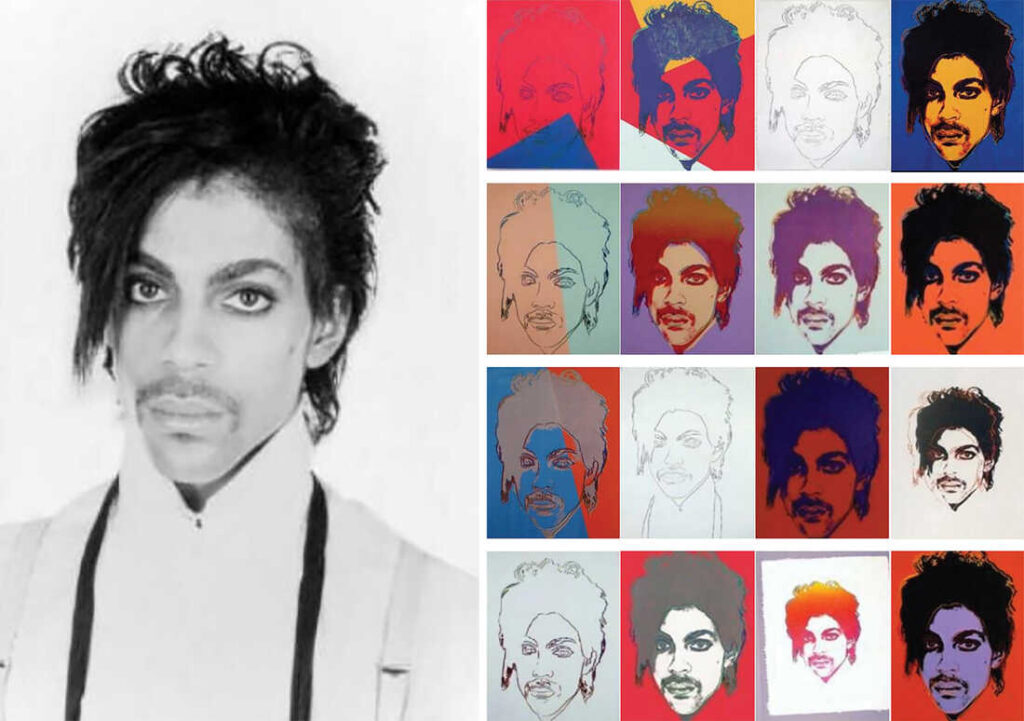

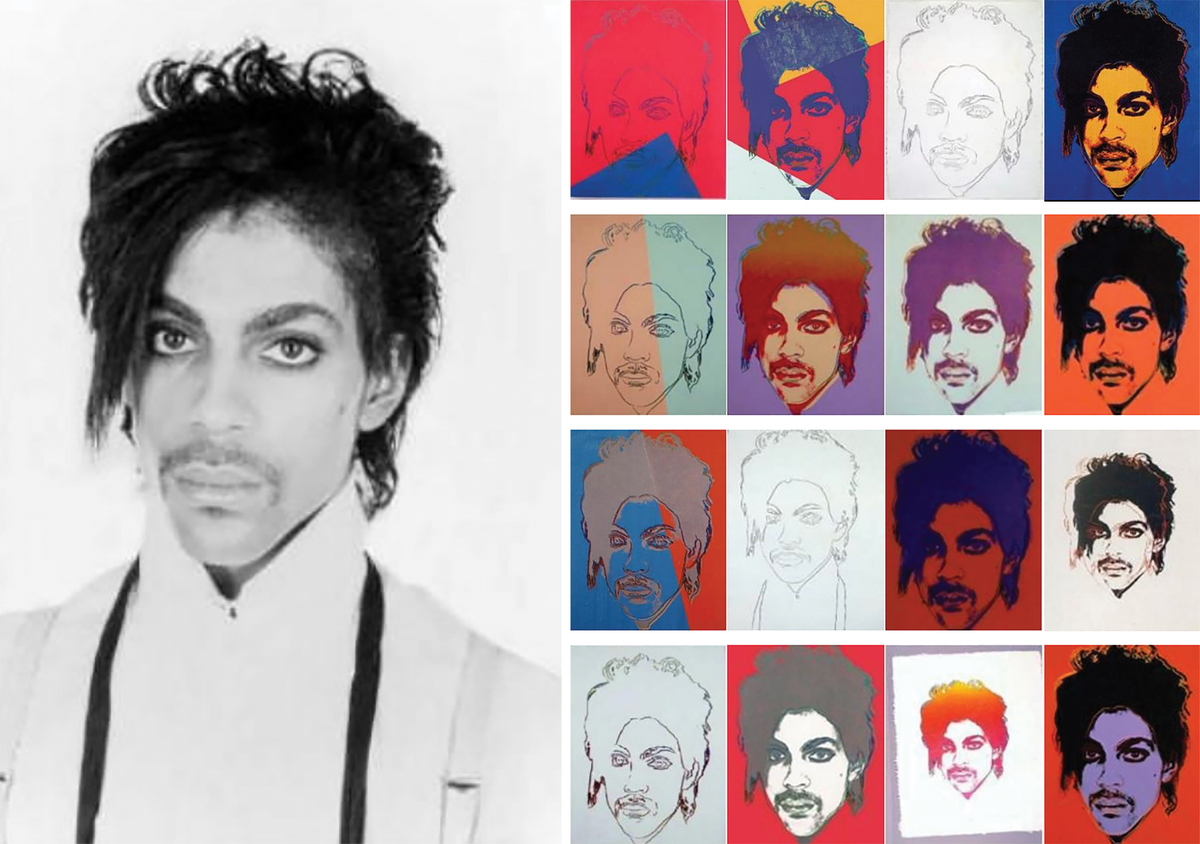

A portrait of Prince taken by Lynn Goldsmith (left) in 1981 and 16 silk-screened images Andy Warhol later created using the photo as a reference.

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

hide caption

toggle caption

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

A portrait of Prince taken by Lynn Goldsmith (left) in 1981 and 16 silk-screened images Andy Warhol later created using the photo as a reference.

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

In a 7-2 vote on Thursday, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled Andy Warhol infringed on photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s copyright when he created a series of silk screen images based on a photograph Goldsmith shot of the late musician Prince in 1981.

The high-profile case, which pits an artist’s freedom to riff on existing works of art against the protection of an artist from copyright infringement, hinges on whether Warhol’s images of Prince transform Goldsmith’s photograph to a great enough degree to stave off claims of copyright infringement and therefore be considered as “fair use.” Under copyright law, fair use permits the unlicensed appropriation of copyright-protected works in specific circumstances, for example, in some non-commercial or educational cases.

Goldsmith owns the copyright to her Prince photograph. She sued the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF) for copyright infringement after the foundation licensed an image of Warhol’s titled Orange Prince (based on Goldsmith’s image of the pop artist) to Conde Nast in 2016 for use in its publication, Vanity Fair.

Goldsmith did license the use of her Prince photo to Vanity Fair back in 1984, when the magazine commissioned Warhol to create a silkscreen work based on Goldsmith’s photo and then used an image of Warhol’s piece to accompany an article they ran that year about the musician. But that was only for the one-time use of the image. According to the Supreme Court opinion, the magazine credited Goldsmith and paid her $400 at the time for its use of her “source photograph.”

Andy Warhol pictured in February 1980.

John Minihan/Evening Standard/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

John Minihan/Evening Standard/Getty Images

Andy Warhol pictured in February 1980.

John Minihan/Evening Standard/Getty Images

Justice Sonia Sotomayor delivered the opinion of the court.

“Goldsmith’s original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists,” wrote Sotomayor in her opinion. “Such protection includes the right to prepare derivative works that transform the original.”

She added, “The use of a copyrighted work may nevertheless be fair if, among other things, the use has a purpose and character that is sufficiently distinct from the original. In this case, however, Goldsmith’s original photograph of Prince, and AWF’s copying use of that photograph in an image licensed to a special edition magazine devoted to Prince, share substantially the same purpose, and the use is of a commercial nature.”

A federal district court had previously ruled in favor of the Andy Warhol Foundation. It found Warhol’s work to be transformative enough in relation to Goldsmith’s original to invoke fair use protection. But that ruling was subsequently overturned by the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Justice Elena Kagan’s dissent, shared by Chief Justice John Roberts, stated: “It will stifle creativity of every sort. It will impede new art and music and literature. It will thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge. It will make our world poorer.”

Joel Wachs, President of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, shared the two dissenting justices’ views in an emailed statement the foundation sent to NPR.

“We respectfully disagree with the Court’s ruling that the 2016 licensing of Orange Prince was not protected by the fair use doctrine,” wrote Wachs. “Going forward, we will continue standing up for the rights of artists to create transformative works under the Copyright Act and the First Amendment.”

Legal experts contacted for this story agreed with the Supreme Court’s decision.

“If the underlying art is recognizable in the new art, then you’ve got a problem,” said Columbia Law School professor of law, science and technology Timothy Wu in an interview with NPR’s Nina Totenberg.

Entertainment attorney Albert Soler, a partner with the New York law firm Scarinci Hollenbeck, said that the commercial use of the photograph back in 1984 as well as in 2016 makes the case for fair use difficult to argue in this instance.

“One of the factors courts look at is whether the work is for commercial use or some other non-commercial use like education?” Soler said. “In this case, it was a series of works that were for a commercial purpose according to the Supreme Court, and so there was no fair use.”

Soler added the Supreme Court’s ruling is likely to have a big impact on cases involving the “sampling” of existing artworks in the future.

“This supreme court case opens up the floodgates for many copyright infringement lawsuits against many artists,” said Soler. “The analysis is going to come down to whether or not it’s transformative in nature. Does the new work have a different purpose?”

Wu disagrees about the ruling’s importance. “It’s a narrow opinion focused primarily on very famous artists and their use of other people’s work,” Wu said. “I don’t think it’s a broad reaching opinion.”