On a late spring morning 50 years ago this week, 30,000 people gathered outside the baroque facade of the church of San Francisco in central Lima to weep, sing and say goodbye to the young woman whose coffin was hoisted on to the crowd’s shoulders and carried, for three hours, to El Ángel cemetery a few kilometres away.

Lucha Reyes, who had died the previous day from a heart attack brought on by diabetes, knew her end was approaching. In keeping with the raw and pained songs and performances that had made her Peru’s darling, the 37-year-old singer had even commissioned a valedictory waltz. Called Mi última canción, or My Last Song, it was written in a funeral parlour.

Reyes died on 31 October – the day her country celebrates música criolla, the fusion of waltzes and Afro-Peruvian and Andean styles that she and her songs embodied. In the five decades that have since passed, Peru has never forgotten the singer known as its Morena de Oro, or Golden Black Woman. Her songs can still be heard in malls, markets and on crowded buses in Lima’s traffic-choked streets, even if younger ears may struggle to identify the singer. But, as the 50th anniversary of her death approaches, efforts are under way to bring her music to a new audience.

In June, Peru’s culture ministry declared her a “meritorious cultural figure”, posthumously recognising Reyes for her “artistic value and for her contributions as a fighter for her own rights, who opened the way for Afro-Peruvian women”.

Six thousand miles away in Madrid, a record label created to introduce female Latin American singers to global listeners has just released a collection of her songs on vinyl and for download. “I may be part of the last generation that is really aware of her,” says Jalo Núñez del Prado, the Madrid-based Peruvian music producer behind the Ellas Rugen (Women Who Roar) label.

“You hear Lucha Reyes everywhere, and although a lot of people recognise the songs, they don’t know about the person who sang them. I want people to find out about her and what she was like.”

The biography of the woman born Lucila Justina Sarcínes Reyes in Lima on 19 July 1936 does not make easy reading. One of up to 15 siblings – no one is quite sure – she lost her father young and was singing on the streets and in bars at the age of five to help support her mother. Her childhood and youth were marked by poverty, a fire that burned down the family home, time in a convent and, aged 16, an attempted rape by her stepfather.

Menial jobs followed, as did marriage to a policeman who abused her physically and emotionally. In 1959, she spent a year in hospital after she was misdiagnosed with tuberculosis when, in fact, she was suffering from diabetes, oedema and dyspnea. Later, the misdiagnosis would give rise to the myth that her distinctive voice was the result of damage done by TB to her vocal cords.

As Núñez del Prado points out, the word lucha also means struggle, or fight. “Even her name speaks of the struggles she faced and of which she became a symbol,” he says. “She was a woman; she was black and she was poor. But thanks to her amazing artistic talents, she became a star, even though life had dealt her a bad hand.”

By 1960, Reyes’s luck had started to change. Having sung at parties and on the radio, she was scouted as a singer by the Peña Ferrando, a musical caravan that toured the country ceaselessly and was one of Peru’s seminal television shows. She then joined the famous Peña Karamanduka and swiftly built a following.

Her songs of love, loss and heartbreak, delivered with drama and a sincerity that was all-too-lived, grew in popularity as Peruvians embraced música criolla. In 1970, she recorded her first album, La morena de oro del Perú. It would be followed by three more in just three years: Una carta al cielo (A Letter to Heaven); Siempre criolla (Always Creole) and Mi última canción.

Her rise coincided with the government of General Juan Velasco Alvarado, who came to power after a coup and whose reformist administration was keen to use música criolla as a means of promoting a coherent national identity and resisting the dissolute and druggy rock music wafting down from the US.

Despite Reyes’s litany of suffering – and comparisons with Edith Piaf – admirers insist her greatest triumph was to harness that pain and turn it into something achingly beautiful and instantly recognisable.

“Lucha Reyes was a theatrical artist who put everything – good, bad, sad and tough – at the service of her art,” says the writer and film-maker Javier Ponce Gambirazio, who made a 2009 documentary about Reyes called Carta al cielo. “She was a true alchemist who turned her own disaster into a work of art.”

In each note of her voice, he adds, you can hear the desgarro, a word that translates as anguish and as tear – as in a muscle tear. “But, at the same time, you can hear the absolute joy that singing brings her. It’s almost as if she’s in a trance that may have made her feel as though wading through all that horror had been worth it because of where she’d managed to get.”

Ebelin Ortiz, an Afro-Peruvian actor, television presenter, singer and activist, says Reyes paved the way for black female solo artists in Peru – including Susana Baca and Eva Ayllón – and remains an inspirational figure for black Peruvian women.

“She suffered a lot of mistreatment but she had a voice that dazzled, and I believe, from my perspective as a performer, that she sang with such feeling precisely because of all the mistreatment that she suffered,” says Ortiz. “Lucha’s great legacy was her constant struggle to pursue her own dreams – and how she managed to overcome any form of aggression towards her.”

Back then, she adds, Reyes had to face both racism and misogyny. “Sadly, things haven’t changed that much.”

As Ponce Gambirazio notes, Reyes is also a heroine for many in Peru’s LGBTQ community. Not only was she from the margins of society, she also wore extravagant wigs and performed in Lima alongside the French transgender star Coccinelle.

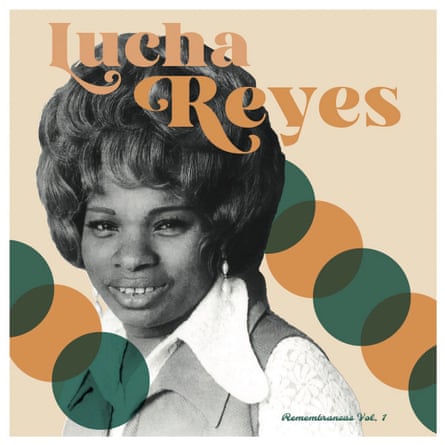

Núñez del Prado hopes the new collection, Lucha Reyes, Recollections: Volume One, will give the singer the global recognition that eluded her.

“The only big difference between Edith Piaf and Lucha Reyes was that the French knew what a jewel they had, and they knew how to export her,” he says. “If Lucha Reyes had had the kind of industry support that people got in England or the US or France, she’d be recognised alongside Billie Holiday because she’s just amazing.”

Ponce Gambirazio does not disagree. It is a measure of Reyes’s enduring power, he says, that one of the few things that all Peruvians can agree on – apart from the deliciousness of their food – is the brilliance of a woman and a voice that fell silent 50 years ago.

“Despite all the antagonistic positions, the sporting, religious, political, social and cultural rivalries and everything else we’ve come up with as an excuse to argue with each other, there’s one thing no one disputes,” he says. “Lucha Reyes is the best. There was no one better – man or woman – before her, and there’s been no one better since. There’s no one like her.”