Dancers perform at a dress rehearsal of the Washington National Opera’s production of Puccini’s Turandot at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. on May 8, 2024.

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

Dancers perform at a dress rehearsal of the Washington National Opera’s production of Puccini’s Turandot at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. on May 8, 2024.

Keren Carrión/NPR

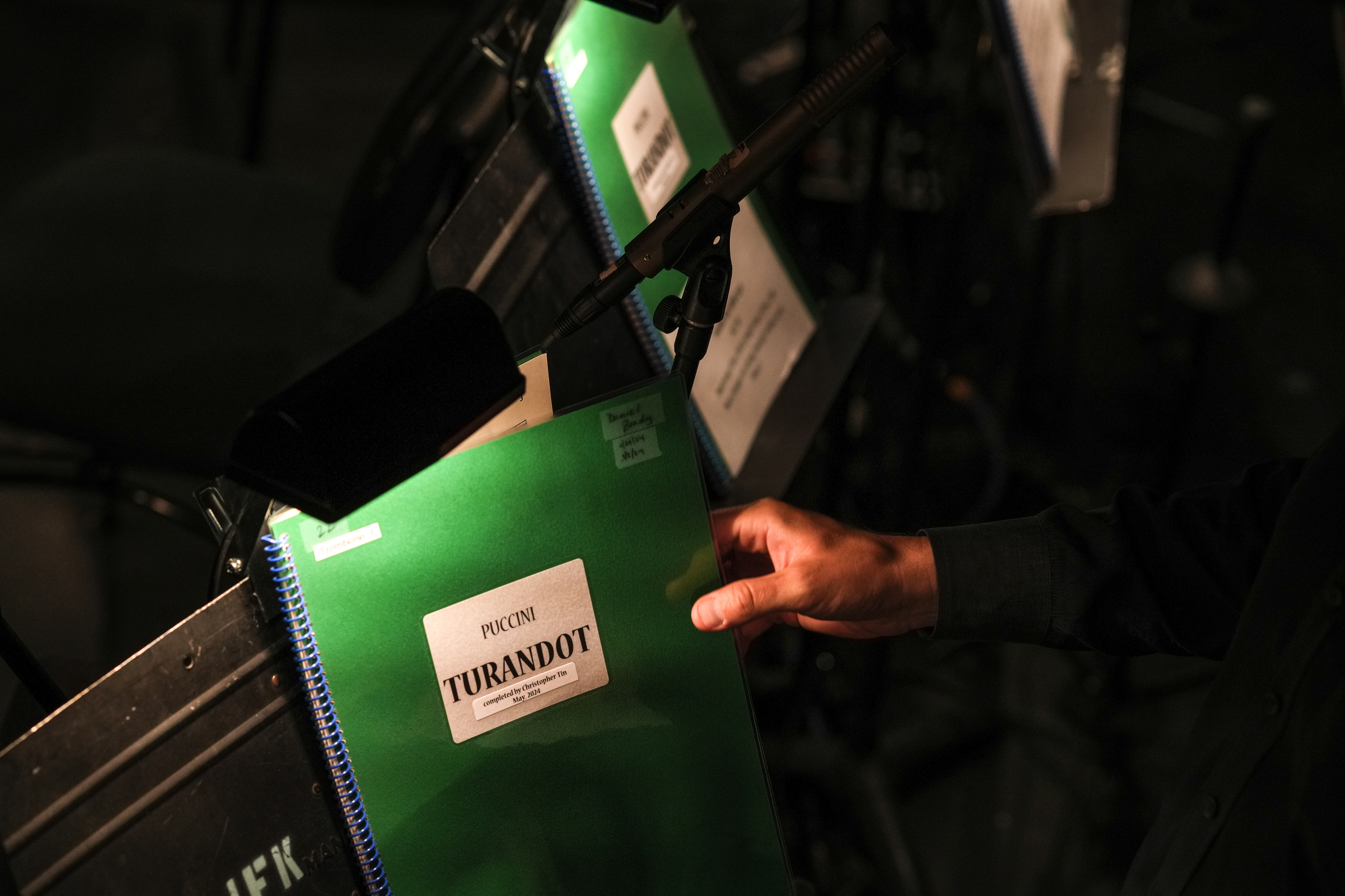

The Kennedy Center premieres a new ending for one of the world’s most famous operas on Saturday in Washington, D.C. The opera is Turandot, and its ending has always been, shall we say, problematic. For a good reason.

Composer Giacomo Puccini died shortly before finishing his masterpiece, leaving just musical sketches for the ending — sketches that his student Franco Alfano filled out posthumously. In Alfano’s version, Turandot simply falls in love with Calaf after a single kiss.

Other opera companies have toyed with different endings over time, but were constrained by the fact that the work was still covered by copyright.

Now, however, 100 years after Puccini’s death, the copyright is expiring. So, in anticipation of that date, the Washington National Opera four years ago commissioned a new ending. More on that a bit later.

Speranza Scappucci conducts singers on stage and the orchestra in the pit for the Washington National Opera’s production of Turandot.

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

Speranza Scappucci conducts singers on stage and the orchestra in the pit for the Washington National Opera’s production of Turandot.

Keren Carrión/NPR

Orchestra musicians settle into their chairs in the Kennedy Center’s Opera House.

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

Orchestra musicians settle into their chairs in the Kennedy Center’s Opera House.

Keren Carrión/NPR

World-famous aria

Turandot is one of the world’s most lush and luscious operas, with its tenor aria “Nessun dorma” recognized not just by opera lovers, but also by those who have never heard a full opera. Performed at multiple FIFA World Cups, the aria has become a pop culture hit of sorts.

That said, however, Turandot‘s story line is probably the most ridiculous in all of opera. The titular Chinese princess has declared that no man will possess her unless he can answer three riddles. Princes seeking Turandot’s hand in marriage come from far and wide, but when they fail, they don’t just have hurt feelings. They are executed. Yes, put to death.

Until Calaf, a disguised prince from a vanquished land, actually succeeds. Turandot is horrified, killing and torturing people to find out who he is. But when he kisses her, she surrenders, declaring that she knows the stranger’s name: it is love.

Washington National Opera artistic director Francesca Zambello, who also directs its production of Turandot, takes her place at the production table ahead of the dress rehearsal.

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

Washington National Opera artistic director Francesca Zambello, who also directs its production of Turandot, takes her place at the production table ahead of the dress rehearsal.

Keren Carrión/NPR

There were no performances of Turandot in China until 1998 — 74 years after Puccini died leaving the opera unfinished — due to the way China and the characters were portrayed in the work.

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

There were no performances of Turandot in China until 1998 — 74 years after Puccini died leaving the opera unfinished — due to the way China and the characters were portrayed in the work.

Keren Carrión/NPR

“I’ve always been frustrated by the ending,” says Francesca Zambello, the artistic director of the Washington National Opera. “I felt like Puccini gave us amazing women in all of his operas. The conclusion might be death but usually the death is a kind of triumph, whether its Tosca or Butterfly.”

As she observes, none of those women’s modernity or independence is present in the traditional Turandot ending: “He kisses her and she’s like, okay, fine, I’ll do whatever you want.”

A more female-empowered ending

Zambello wanted something different, to correct the way China and the characters were depicted in the work, stereotypes that provoked China to effectively ban the opera until 1998.

And Zambello also wanted to portray Turandot as a leader. To accomplish her twin goals, she commissioned two Chinese Americans to create a different ending. For the music, she chose Grammy Award-winning composer Christopher Tin. And for the libretto, playwright Susan Soon He Stanton, who won an Emmy for her work on TV’s “Succession.”

The new ending commissioned by the Washington National Opera marked Susan Soon He Stanton’s first libretto; she is best known as a writer/producer for HBO’s series “Succession,” which won her an Emmy.

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

The new ending commissioned by the Washington National Opera marked Susan Soon He Stanton’s first libretto; she is best known as a writer/producer for HBO’s series “Succession,” which won her an Emmy.

Keren Carrión/NPR

The new ending explains Turandot’s (Ewa Płonka) icy demeanor by expanding on the abduction and killing of her female ancestor and her own subsequent rape during an attack on the palace.

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

The new ending explains Turandot’s (Ewa Płonka) icy demeanor by expanding on the abduction and killing of her female ancestor and her own subsequent rape during an attack on the palace.

Keren Carrión/NPR

In explaining Turandot’s motivations, the duo sought to emphasize the reason for her hostility to men, with a plot twist. Turandot is not only avenging the abduction and killing of her great female ancestor, Princess Lo-u-Ling, but also her own subsequent rape during an attack on the palace.

This is Stanton’s first attempt at writing words for opera. And her first draft was as she puts it, “one huge scene.” Zambello told her that as written, that scene alone would probably take over two hours just to sing because in opera, “every sentence takes time.”

No ‘second-rate Puccini’

For composer Tin, the task was perhaps even more delicate. He wanted to use as many of Puccini’s musical sketches as possible for the ending.

“But that said, I also don’t want to slavishly try to impersonate Puccini, because nobody wants to hear a second-rate Puccini, but maybe somebody might want to hear a first-rate Christopher Tin,” he adds.

Some of the corps dancers get ready for the dress rehearsal of Turandot.

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

Some of the corps dancers get ready for the dress rehearsal of Turandot.

Keren Carrión/NPR

Zoë Brielle Payne, along with other female dancers, puts on makeup for the dress rehearsal.

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

Zoë Brielle Payne, along with other female dancers, puts on makeup for the dress rehearsal.

Keren Carrión/NPR

The 18-minute new ending does in fact reprise some of the themes heard in the earlier parts of the opera. “Sometimes in very subtle ways, sometimes in clever ways,” Tin says, noting that at one point he used a Puccini melody but inverted it.

The point, he adds, was to anchor his ending as much as possible to the two and a half acts actually written by Puccini “to make the whole thing as satisfactory and complete of a musical experience as possible.” So, for instance, the new ending features echoes of “Nessun dorma.”

Tin says he set aside four months, without any other work, to devote to this project.

“The reason I jumped into this commission without hesitation was the fact that I like to write hummable melodies,” he says, wryly adding that hummable melodies are “not exactly in vogue, or haven’t been in vogue in classical music for a while now.” Indeed, he agrees, hummable tunes are not even “in” on Broadway these days.

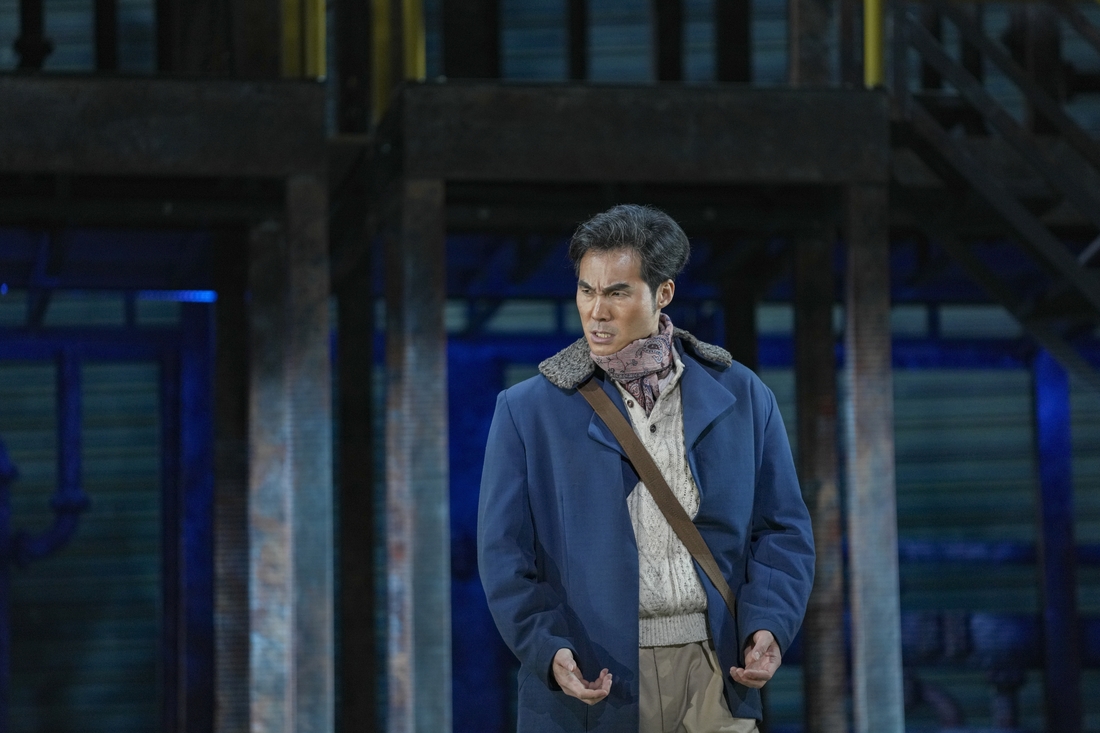

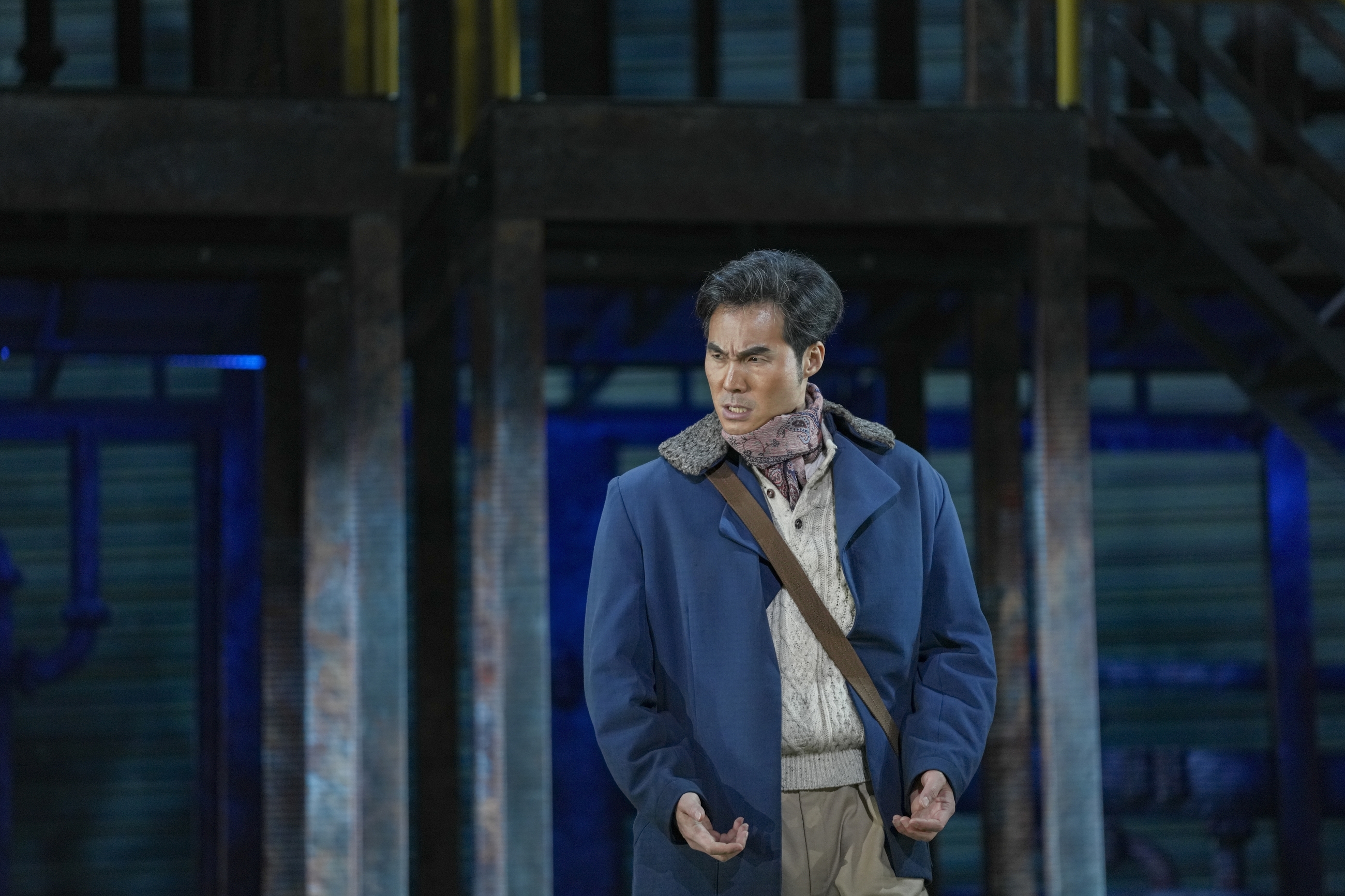

In Turandot‘s original plot, the titular Chinese princess gives suitors three riddles. Princes who fail are executed, until Calaf (Yonghoon Lee) succeeds and wins her heart by kissing her.

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

In Turandot‘s original plot, the titular Chinese princess gives suitors three riddles. Princes who fail are executed, until Calaf (Yonghoon Lee) succeeds and wins her heart by kissing her.

Keren Carrión/NPR

Christopher Tin, best known for his video game and film soundtracks, composed a new ending for Turandot by drawing inspiration from Puccini’s surviving musical sketches.

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

Christopher Tin, best known for his video game and film soundtracks, composed a new ending for Turandot by drawing inspiration from Puccini’s surviving musical sketches.

Keren Carrión/NPR

But Tin, who is best known for his film and video game soundtracks, prides himself on making his work accessible. “To me if you’ve come up with a great melody, boy, you’ve done 80% of the work, right there,” he says. “A great tune lasts forever.”

For librettist Stanton, the commission was a great opportunity to right the wrongs of Asian stereotypes. “This is our real chance, especially we’re both Chinese American artists, being able to be a part of this conversation, and so I think it was a huge responsibility,” she says.

Out with the stereotypes

For instance, the characters of Ping, Pang and Pong are instead called by their ministerial titles: Chancellor, Majordomo and Head Chef.

In the last analysis though, the ending represents something of a complete U-turn for both main characters, not just Turandot, but also Calaf.

The WNO production called the characters Ping, Pang and Pong by their ministerial titles instead (R to L): Chancellor (Ethan Vincent), Majordomo (Sahel Salam) and Head Chef (Jonathan Rhodes).

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

The WNO production called the characters Ping, Pang and Pong by their ministerial titles instead (R to L): Chancellor (Ethan Vincent), Majordomo (Sahel Salam) and Head Chef (Jonathan Rhodes).

Keren Carrión/NPR

The Washington National Opera’s production of Turandot places China at a cultural crossroads, with people of various origins coexisting.

Keren Carrión/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Keren Carrión/NPR

The Washington National Opera’s production of Turandot places China at a cultural crossroads, with people of various origins coexisting.

Keren Carrión/NPR

Earlier in the opera, Calaf sings “Nessun dorma” in a moment of “toxic masculinity,” Tin says. “He knows he’s won. He’s gloating. China’s miserable. This is his victory lap. [But] now he’s the guy who believes that love is the thing you need to be willing to die for and sacrifice your own life for.”

And Turandot? Calaf persuades her not to be a vengeful princess, but a loving and forgiving one. So she orders that Liù, the slave girl who killed herself rather than betray Calaf, is to be buried next to Turandot’s ancestor, Lo-u-Ling.

A fairytale world

If all of this sounds like a fairy tale, it is.

“To me, you have to stay in this fairytale world in order to make this work,” Tin says. “A fairy tale where the two primary lovers do not actually fall in love at the end is not a fairy tale that I want to tell my daughter. And so our task was, how do you get to that happy ending, especially given how ridiculous a lot of the plot points in the whole preceding two and a half acts are.”

And ridiculous or not, it’s glorious!

The broadcast version of this story was produced by Julie Depenbrock and edited by Olivia Hampton, who also edited the digital version.